Just when I thought I was out, the clinic pulls me back in.

Though I’m glad to be back. There’s just a different vibe, different pace, and ever-constant variety of challenges that being in the clinic simply provides. This has been especially true working in a rural area. You see a much wider variety, which challenges you to broaden your skillset.

I’m amazed at how much working in the NBA has changed the way I approach the clinic.

Previously, I was all about getting people in and out of the door as quickly as possible; and with very few visits. I would cut them down to once a week or every other week damn-near immediately, and try to hit that three to five visit sweet spot.

This strategy no doubt worked, and people got better, but I had noticed I’d get repeat customers. Maybe it wasn’t the area that was initially hurting them, but they still were having trouble creep up. Or maybe it was the same pain, just taking much more activity to elicit the sensation.

It became clear that I was skipping steps to try and get my visit number low, when in reality I was doing a disservice to my patients. This was the equivalent of fast food PT—give them the protein, carbohydrates, and fats, forget about the vitamins and minerals.

Was getting someone out the door in 3 visits for me or for them? The younger, big ass ego me, wanted to known as the guy who got people better faster than everyone else. Yet the pursuit became detrimental to the patient’s best interest. There were so many other ways I could impact a patient’s overall health that I simply sacrificed in place of speed.

I only got them to survive without pushing them to thrive.

I see a lot of individuals proudly proclaim how many visits it takes for them to get someone out of pain, but pain relief is only part of the equation. There are so many more qualities we can address before we consider a rehab program a success.

This stark realization has reconceptualized how I structure a weekly rehab program. I now emphasize all qualities necessary to return to whatever task the patient desires, and attempt to inspire them beyond those initial goals.

You want to know what my visit average is right now?

I stopped counting, and started treating.

Let’s look designing the rehab week to take your clients to the next level.

Table of Contents

The Keys to a Rehabilitation Program

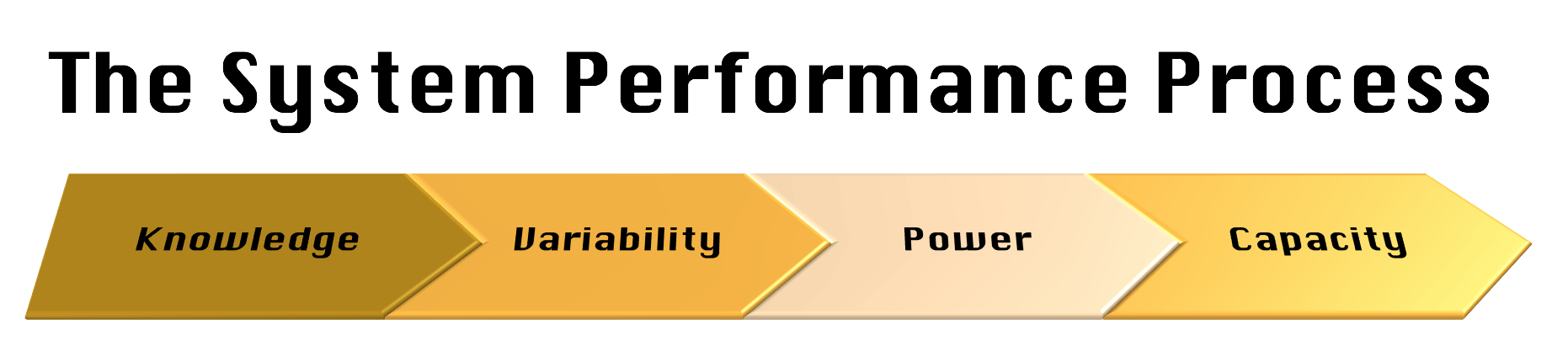

All body systems have four basic components that can be altered. Consider the definition of each of these components relevant to any system, but we will look at how these pieces impact movement system in particular. The movement system is the primary target of most rehab and training modality.

Here’s what you’ll look at:

Knowledge

Knowledge is having the requisite understanding to perform. This component includes any education form that enhances movement capabilities. Any type of explain pain/therapeutic neuroscience education, biomechanical explanations, post-surgical education, etc would fit here.

If someone has fear avoidance, thinks that pain equals tissue damage, or is breaking their post-operative restrictions, you likely have a knowledge problem.

Variability

Variability is the ability to perform within a desirable range. For the movement system, possessing and controlling a desired joint range of motion is how variability is established.

Most therapeutic exercise, manual therapy, and modalities seek to improve movement variability. If I can reduce someone’s pain, and consequently they can move more effectively, then variability has increased.

If someone has pain with a simple movement, joint mobility appears limited, or someone is hypermobile with motor control deficits, you likely have a variability problem.

Power

Power is the ability to produce intensity. A rehab-oriented power approach would focus on load tolerance, force production, and velocity achievement.

Any method that emphasizes force production—resistance training, sprinting, jumping, agility training— fits here.

If someone demonstrates requisite variability and motor skill, but hurts or cannot perform loaded or power-producing movements, you likely have a power problem.

Capacity

Capacity is the ability to sustain a given intensity. Moving for a desired period of time without pain or reduced performance fit the bill for this quality, and are trained by any conditioning method.

If someone can perform most activities, but pain or fatigue is elicited after a particular duration, then you likely have a capacity problem. Examples include a runner who starts to feel pain after mile 5, someone who hurts after sitting for 90 minutes, or a grandma who can only perform 3 sit to stands before needing a rest.

Prioritizing Movement Problems

Now that you have a framework to categorize impairments, you may now prioritize which ones are most important to the client’s success.

The order that I listed these categories in is important, as it ranks which qualities must be addressed first. Fixing problems early in the process can have a trickle down effect on terminal impairments.

For example, I could have an individual who has limited neck mobility, cannot tolerate any sitting duration whatsoever, and is afraid to move the neck because he or she hears a creaking noise when the action occurs. You likely will not get far in improving variability and capacity in this patient until that individual accepts the knowledge that the creaking noise is not a problem. Addressing the knowledge problem in this case is the primary target, and could restore a bulk of the mobility deficit.

If the above individual lacks fear avoidance, increasing variability before attempting graded exposure to sitting could provide enough degrees of freedom to reduce the evident ischemia production from sitting. In this case, perhaps no capacity training is needed.

How to Implement a Home Exercise Program

The home exercise program (HEP) or homework ought to target the primary problem. The HEP is the first line of defense to eliciting change. Client ownership and accountability is really the only way to have long term success.

Once the HEP has been successfully and soundly performed under your supervision, recheck your objective measures and see what impairments remain. Whatever problems persist ought to be the focus on addressing those areas. If nothing changed with the HEP, then the program must be changed.

For example, if you have someone with a hip mobility deficit, and the HEP satisfies addressing the mobility improvements in your relevant objective test, then you ought to shift the initial variability focus to something else for the session remainder. Options could include motor control within the new range (variability), loading movement patterns in an already established “safe” range (power), or performing some endurance work in a relevant position that exploits a particular range (capacity).

Let’s say that the HEP only partially satisfies the initial goal and you need an even greater emphasis on this quality. The session remainder can focus on using other interventions to attack that problem. In the case above, we could use manual therapy, isometric holds, maybe you slather peanut butter over the affected region and hold a seance while Phil Collins is playing in the background, whatever method leads to further improvement in said quality.

Now that we know what qualities to improve and prioritizing them within a program, let’s look at what a typical week for a client may look like.

The Weekly Rehab Plan

Once you’ve determined the client’s needs to succeed, it’s time to structure the game plan over the week.

In my current setting (7/2017), I see most of my in-person clients one to two times per week, with each session lasting around 45 minutes. Fortunately all sessions are one-on-one.

I try to structure each session in the following manner:

The First Session

The first day of the week introduces and updates the HEP. I will perform all my objective testing, and pick 1-2 activities that can relevantly address the primary impairment.

Establishing the HEP often takes up the entire session. There is an important reason for this time consuming endeavor. Consider that there are 10,080 minutes in a week, and I am only seeing an individual for 90 of the minutes at the most. That means I am monitoring their actions 0.89% of the week.

Let that sink in for a moment. You are only working with your clients less than 1% of their given week. How big of an impact you think you can make in such a miniscule portion of a person’s life? It could be substantial, but it could be minimal.

If you want to safeguard your outcomes, have the client be the person who will make the largest impact his or her life.

You must do all in your power to ensure that your clients have the best tools and tactics necessary to be succeed at the remaining 99% of their lives. If your client performs the HEP poorly enough to negative improvements, or worse yet, not doing, you will fail. Period.

Now you know why I spend the entire session coaching the hell out of the HEP in that 45 minute block. It’s the only way our clients have a shot at winning. Moreover, prescribing the minimal effective dose of one to two moves increases likelihood of adherence. The more exercises in the program, the less likely your client will do the work at home. If nothing is done at home, you lost the 99%, and wasted both your time and the client’s.

If we can only prescribed 1-3 moves, you have to be laser like in exercise selection. If you know addressing area x will give the client the biggest bang for his or her buck, that’s where efforts must be focused. If you can demonstrate a favorable change within session that is meaningful for the client, they will more likely perform the task at home.

Though sometimes despite having demonstrated a favorable change for the client, logistics make the chosen move tough for your client to perform. Maybe you’ve provided a technique where the patient has to be lying down, but his or her bed is too soft or they can’t get up and down off the ground. Having backup plans in these cases are essential. This is why I keep a lot of activities, especially for older individuals or extremely busy parents, in standing or sitting. While I may not get as good of a change in other positions, I’m more likely to have a positive impact because I have better compliance.

The Second Session

The second session starts with a brief HEP review to fine tune the client’s performance of the program. Proper performance will address the primary rehabilitation target, so make what they’re doing look pretty.

After that, the session remainder focuses on the secondary rehabilitation target. A session could contain manual therapy to further improve variability, loading the affected region to build power, BFR lifts to improve capacity, anything really. You could even combine interventions if desired. Whatever is prioritized next depends on the idiosyncratic needs of the individual.

Case Examples of the Rehabilitation Plan

Let’s better illustrate this with a few case studies. I know that some of you fine people work with greater time constraints than I, so I’ll tell you what I’d cut if I only had 30 minutes with a patient.

If you have less time than that…well...I’ll pretend I didn’t hear that.

Lower Back Pain with Prolonged Standing

I have a gentleman who is about to retire in a couple months (yay!) who has developed lower back pain. He has a history of a disc herniation that was surgically cleaned up. Onset of this most recent pain bout was insidious.

Currently, he’s doing pretty well. Is back to lifting heavy things without trouble; something he’s been unable to do for years. At this point, he predominately has trouble with prolonged standing, which he has to do in order to return to work.

Given this history and based on the objective testing we’ve done, we established predominant limitations in both variability and capacity:

Variability: Limited frontal and transverse plane lumbopelvic mobility

Capacity: Standing Tolerance

Thus, his program focused improving mobility and standing conditioning.

Let’s look at what his week looks like.

HEP Establishment (First Session)

30 minutes: Session focused on coaching one exercise to improve frontal and transverse plane lumbopelvic mobility.

15 minutes: Kettlebell deadlift for multiple sets to build standing fitness.

If I had only 30 minutes, I would cut out the kettlebell deadlift and focus on HEP establishment.

Capacity Training (Second Session)

10 minutes: Reviewed HEP from first session

35 minutes: Remaining 35 minutes was a weighted circuit to build standing capacity. I used the following moves, which also reinforced sagittal plane motor control and hip mobility:

- Single leg RDL slide

- Counterweight split squats

- Split Stance Low cable row

We did a few rounds of 8-10 reps and he was decently gassed.

If I had only 30 minutes, I would reduce the set number on HEP, and cut the rest periods on the circuit.

Shoulder Stiffness Post-Bankart Repair

Have a 25 year old guy who is being seen post-operatively for a left Bankart Lesion repair and capsulorraphy. He puts in work on his own to stay conditioned, but is battling post-surgical shoulder mobility limitations. He has just been cleared to begin active-assisted range of motion.

The predominant focus for this cat is increasing variability. We can’t force external rotation at this point, so the large emphasis has been improving flexion and abduction.

Here’s what it looks like in his case:

HEP Establishment (First Session)

35 minutes: I gave him two exercises to focus on lat and pec inhibition that are active assistive in nature. I have him do 5 sets of 5 breaths of each to be certain the volume was adequate to change range of motion.

He was also having some trouble (limited internal rotation) on his right side with some pain. Here is how I could get him true shoulder flexion while helping out his right side:

10 minutes: Ribcage mobilizations to further augment mobility.

If I had only 30 minutes, I would skip the manual therapy and reduce the volume of the HEP.

Progressive Variability Acquisition (Second Session)

10 minutes: HEP review

35 minutes: Manual therapy which included ribcage mobilizations and dry needling. He absolutely loved the latter, which both increased his active flexion by 20 degrees and eliminated the pinch he was getting end-range.

If I had only 30 minutes, I would’ve cut the amount of time I spent needling.

Hypermobile Post-Operative ACL repair

This young woman had a traumatic left ACL tear from a biking accident. Her graft choice was a combo hamstring and cadaver graft.

She is an incredibly flexible chica who has full passive extension; limited flexion. She has a slight deficit of an active quad set, and has trouble extending the knee at relevant points in the gait cycle.

Here we can see this woman has needs in both the variability and power department, which include the following:

Variability: Restore knee mobility and frontal plane hip mobility

Power: Mitigate quadriceps atrophy and build single leg power to normalize gait

Here is what her week looked like.

HEP Establishment & Structural Power (First Session)

30 minutes: Taught her a new home exercise program that focused on the squatting bar reach and frontal plane hip mobility. She couldn’t fully adduct her left hip, but after the activity below not only did she achieve full adduction but gained 15 degrees of knee flexion. Pretty incredible change for her:

15 minutes: Blood flow restriction training (BFR) to improve quadriceps hypertrophy and power. I used step-ups. It was brutal.

If I had 30 minutes, I would’ve given her only one HEP and kept the BFR. Yes, I sacrificed the home program, but BFR is too damn evidence based to skip.

Functional Power (Second Session)

10 minutes: Reviewed HEP.

35 minutes: Power session that emphasized single leg-based progressions. We also reinforced some of the double limb stuff we worked on previously. I offset the weight on a lot of these exercises to establish frontal plane motor control since we had acquired some new mobility.

Here was her program:

- Kettlebell deadlift

- Split squats – Contralateral offset weight

- Step-ups – Contralateral offset weight

If I only had 30 minutes, I would’ve cut the rest periods and sets.

Sum Up

That, my friends, is a week in the life of a patient with me. By prioritizing relevant impairments, and intelligently planning a program, you will better serve your clients. Not just to get them out of pain, allow them survive, but inspire them to thrive.

To summarize:

- Focus the needs of your client, not the needs of your ego

- Knowledge first, variability second, power third, and capacity last

- Prioritize which impairments the client must focus on first

- the home exercise program ought to address the primary impairment

- The remaining time spent with patients should be skilled activities that address remaining impairments

How do you structure a week for your clients? Comment below and let us know.