Getting hurt. It happens. Many times when it does, your mind will end up racing. What should I do? Should I go see a doctor? Do I just wait it out? What can I do to help me get back on my feet faster?

Without a guide, these questions may seem impossible to answer.

Until now.

Check out today’s podcast and post that creates for you a standard operating procedure anytime an injury is sustained.

Enjoy!

Table of Contents

You’re Hurt, Now What?

Suppose an injury was sustained. What do you do from here, whether It’s yourself or a client?

We first have to ask ourselves one question.

How serious is this?

Which leads us to the decision of if we should seek medical attention for this problem or should we not?

We first have to talk about what scenarios require medical attention. I’ve talked about the ruling out process before, but there are certain scenarios in which immediately seeking medical attention is warranted.

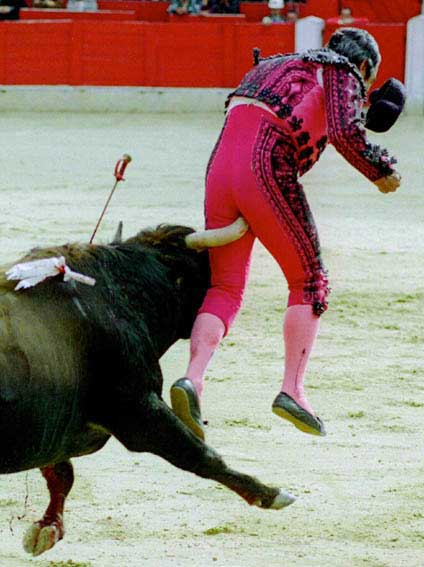

Scenario 1: Traumatic Injuries

If some type of traumatic event is associated with the injury—you did X and Y was the result—and things such as immense pain, swelling, bruising, redness, loss of function, and heat are present, you need to go seek medical attention.

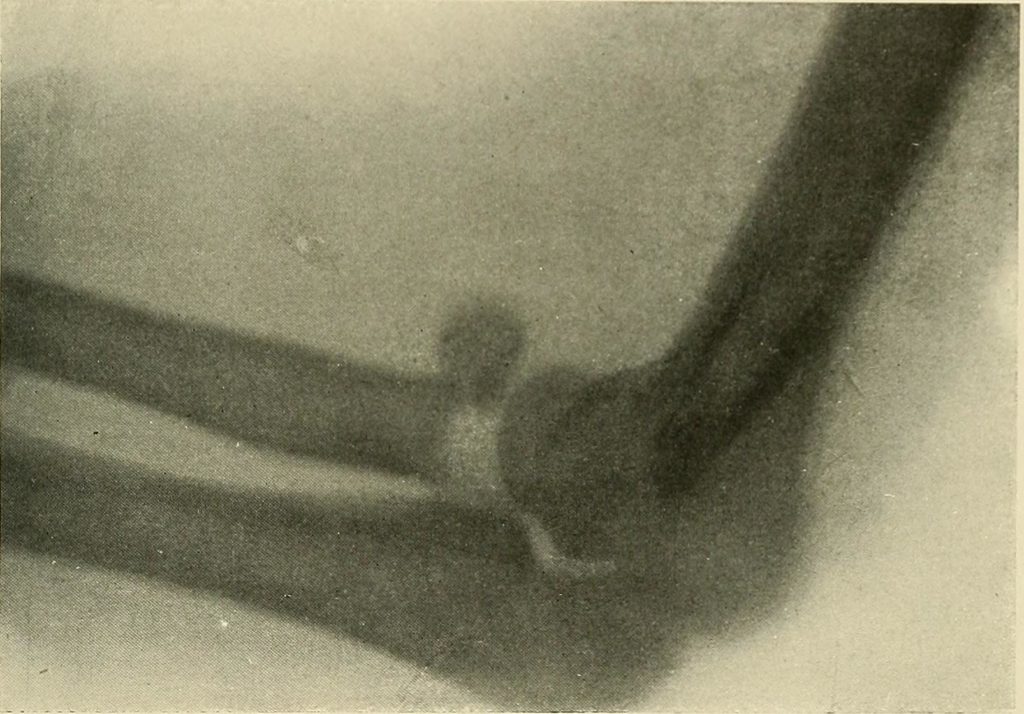

Let me give you an example. I was playing basketball with a colleague of mine. I was setting up for a rebound, and she ran into me, fell on her arm, and began to feel immense pain; couldn’t move her forearm in any direction. I tried to do an assessment, but she was too painful to look at. She went to the emergency room, got x-rays, and was diagnosed with radial head fracture.

That right there, as much as I did not want to admit it at the time, was a clear-cut case of an injury that needed medical attention. The natural course of the healing process wasn’t going to fix the problem, nor was voodoo flossing or silly breathing exercises.

If trauma is at play, and inflammatory signs and symptoms set in quickly, then you definitely need to seek medical attention.

Getting sustained numbness, tingling, sensory loss, or pain down in the arms, legs, or genitals; as well as bowel and bladder changes, are grounds for immediate referral. Some of these could potentially be life threatening or severe long-term consequences.

Scenario 2: Atraumatic Injuries

What about when pain creeps in without trauma? These scenarios do not always require medical referral.

Understanding the normal healing process, and the duration of the inflammatory process, will better help you make the referral call.

After you sustain an injury, the inflammatory process sets in, (learn more here), and is a necessary part of healing. This process must be respected, and often pain increases when inflammation is present.

The normal amount of time for an inflammatory process to occur is anywhere from three to seven days. So within that first week of an injury, expect pain to be high and not improve much. This is normal. As we pass that inflammatory time period, pain ought to reduce.

Now what if after two weeks you have had absolutely no change symptoms, or symptoms worsen? This goes against normal healing times and may be an onset of central sensitization, which happens in the beginning phases of chronic pain. The amount of pain experienced does not match the amount of tissue damage that has occurred.

In these cases, the sooner you can seek medical attention the better. A practitioner might be able to break that inflammatory cycle if chronic inflammation is setting in, or they may be able to break that chronic pain experience that may be setting in.

Point being, if nothing has changed in two weeks, seek medical attention.

Creating a Healing Environment

How can the normal healing process be facilitated and maximized?

Sadly, there is nothing (aside from drugs, which I am not advocating) that can expedite the healing process. There is nothing that can make the inflammatory process go faster, and I don’t necessarily think that we want it to go faster. Inflammatory process is critical to clean up debris, prevent infection, and to heal the injured area. We want to provide an environment that allows inflammation to run its course.

The biggest key is making sure you’re already healthy to begin with. Are you sleeping adequately? Is your diet healthy? Are you exercising regularly? Do you manage and mitigate stress to the best of your capabilities? All of these things matter with providing an adequate healing environment. You’re not going to heal as well getting injured in a stressful state. If your normal state is stressful, then you’re more likely to experience chronic pain and that’s going to negatively influence healing times.

Once you get hurt, rest is warranted. It’s OK to rest. It’s OK to chill, especially for the first few days. You want to move as much as you can but not so far that you are making the pain worse, and potentially propagate the inflammatory process. For example, if you hurt your knees and there is a little bit of swelling, then it’s probably not the best idea to squat. You may want to chill for a little bit. Allow the inflammatory process to happen.

Protect the injured area

I would also do things to protect the injured area. That could be taking things such as fish oil and curcumin to help reduce inflammation with fewer negative side effects. Perhaps at the tail end of the inflammatory process (the last 3 days), taking some type of anti-inflammatory to ensure that inflammation starts to taper off as it should. We can’t always rely on our body processes to work the way they need to, especially considering the chronic stress life we live in. Despite our best efforts, we may not be in the best of health, and our body processes may not be as effective as they should be.

Other ways to protect the area include elevating and compressing the injured area to help swelling return to the lymphatic system. Ice can help dull pain and reduce the speed at which C-fibers fire. Taping to limit motion to those only pain-free can also be beneficial. so.

Incorporating movement to facilitate healing

Movement is critical as well post-injury. Moving the non-injured areas can help with fluid movement, keep body maps refreshed, and maintain fitness. I strongly encourage people that if they sustain a lower body injury to keep training upper body stuff.

I remember when I was in the D-League, we had a guy tear his ACL. I told him the day that he tore it that rehab starts tomorrow. After the doctor’s visit, we got in the gym and we got after with some upper body stuff and maintained lower body as best we could. We wanted to keep his fitness up as high as possible, because fitness is protective of chronic pain, helps the healing process, and would likely give him a better post-surgical outcome.

Aerobic exercise is also critical. I generally try to encourage my people to make the shift to some type of aerobic exercise when they hurt themselves. Increasing systemic circulation will also increase local circulation, and blood is what helps us heal.

Recondition injured tissues

As the injury process runs its course and pain starts to get dulled down, we need to expose the individual to loading the affected region. Generally, what I recommend is making sure that variability is restored first. Making sure all joints in the body have enough variability may help normalize loading strategies, making for an evenly distributed workload across the body.

Once variability is restored, then we can focus on loading the injured area. Isometrics work wonders as a beginning loading strategy in a variety of movement patterns.

I also really like blood flow restriction training (BFR). BFR can increase strength and hypertrophy secondary to cell swelling created via lack of venous return and does so at a very low cost from a one repetition max standpoint (20-30% 1-RM typically). This is essentially free volume at a low risk to the affected region.

Also helpful is progressing people through the concentric-eccentric phase of an early-phase movement at low weights. For example, if squatting was the offending movement, start with goblet squats. Then work towards a 2-kettlebell front squat, and then finish with either a zercher or a front squat. Once you are at the desired movement, add weight until loading is normalized and tolerated.

Once we’ve gone through all of the basic lifts at a low speed, then we can progress to an explosive or ballistic movement. Here is where jumps, med ball throws, plyometrics, and other high speed activities come into play. Speed places much more force on the injured area, but if you have that underlying strength base beforehand, then this loading style is much safer.

Then it’s a matter of slowly increasing volume at a safe rate. Using the acute-chronic workload is a way to safely expose that individual to load in whatever task they’re trying to do. It is a great measure to ensure that you do not do too much too soon, which is a common way that re-injuries occur. We must load the tissues in a manner that allows for both adequate healing and reconditioning. Using something like the acute to chronic workload can help safeguard you from re-injury, though it is by no means a perfect measure.

[If you want an acute:chronic workload calculator absolutely free, then definitely put your email below]

[yikes-mailchimp form=”1″ submit=”Yeah, a free acute:chronic workload calculator sounds dope”]

Sum Up

If you take these steps to returning from injury, then you have a really good chance at 1) Coming out of this injury safely, and 2) minimizing conditioning loss.

To summarize:

- Steps must be taken to ensure if medical attention is warranted in both traumatic and atraumatic injuries.

- Inflammation is a normal part of the healing process, and must be respected

- The healing process cannot be expedited, but steps can be taken to maintain an optimal healing environment.

- Protecting the injured area, maintaining fitness levels, and re-exposing the area the load and stress is crucial to a safe return from injury.

What do you do after you sustain an injury? Comment below and let us know.