It is a common recommendation to immediately refer clients in pain to a medical practitioner.

However, immediate referral is oftentimes not warranted, and in certain cases is discouraged.

But as a trainer, how do you know when a client’s pain is a medical problem, and when is it not?

With today’s podcast, I hope to answer that question for you, as well as give you tips on working with people in pain, and collaborating in a manner that is in your client’s best interest.

Enjoy, and check out the modified transcript below

Table of Contents

Modified Transcript

If you are a trainer, and your client has pain, what should you do?

Well I’m glad you asked.

Many people on the interwebz will make the claim that if your client has pain, you should refer. The reason why this claim is made is 1) because you do not want to make your client problem worse; 2) you also want to cover your ass. If you do something and your client’s problem gets worse, you could potentially get sued. That’s why people say “when in pain, refer out.”

I think that this claim is bullshit, and here’s why.

Reasons why immediate referral can be problematic

There are three negative consequences when you pull the referral trigger too early.

Pain does not equal tissue damage

This claim assumes that pain and tissue damage are synonymous. If you listen to my talk, Practical Pain Education, you would find that this connection is horrendously false.

There are instances in which you can sustain an injury, but not necessarily experience pain—such as when you’re walking around the yard when all of a sudden you realize you’re bleeding because you scraped yourself against a rosebush. Injury but no pain.

An example of which pain is experienced, but not necessarily tissue damage, is stubbing your toe. Hurts like hell. Worse than childbirth I hear. Not really tissue injury happening, but the pain experiences is severe. Or another example of that could be a pebble in your shoe. All of a sudden, your foot starts to hurt, but no damage.

A lot of times we will get random aches and pains. It’s unreasonable and unrealistic to send someone to a clinician every time a random ache and pain happens. Many of us have woken up with a crick in the neck. How many times do we go to a doctor for this? Hopefully not that many, because the natural course of history would lead us to believe that it would get better a couple of days. If you’re a trainer saying This person has got to be a for that, that would be a waste of healthcare dollars. Or maybe you’re walking around the office and hit a random pinch in your ankle. Do you need to go see someone for that? Probably not.

Random aches and pains are normal. They’re expected. And a trainer who knows how to train around pain ought to be able to adapt to that.

Referring out does not mean the problem is solved

When you refer out, you’re operating under the assumption that the clinician is going to fix this problem. A lot of times that’s not the case. You might not have a great medical practitioner in your area to help you. That’s why I have so many trainers reach out to me to work with their clients all over the US.

So what happens if your client seeing a clinician and the problem doesn’t improve, or they’re working with medical for a long period of time and they still want to train? What do you do in that case?

Just because you refer out doesn’t mean the problem is going to be fixed. There are still gains that need to be made.

Immediate referral could have negative consequences

The most egregious problem is thinking any pain experience warrants immediate referral. This process could potentially perpetuate maladaptive beliefs. You may perpetuate the belief that pain means go see physician, means tissue damage.

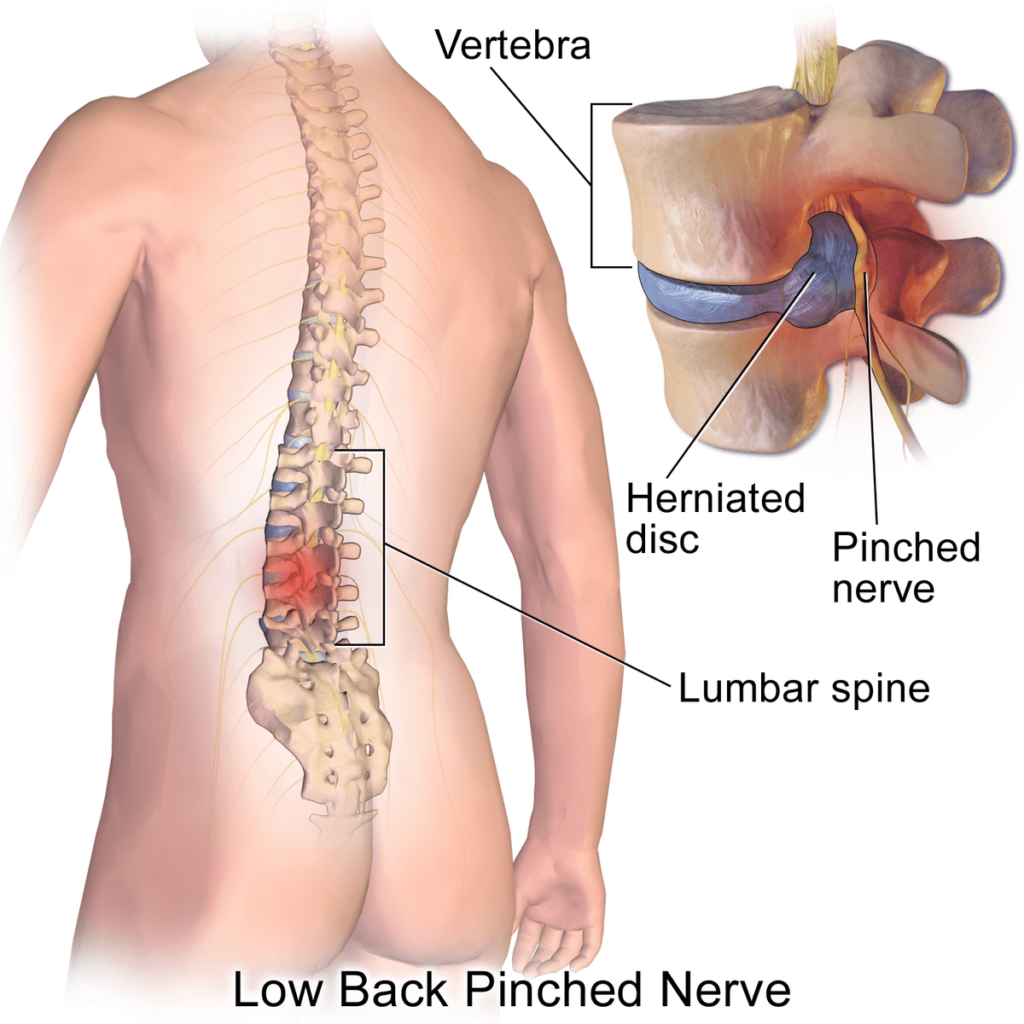

Many times you may send them to a practitioner who requests some type of imaging. That clinician may tell the client that the hurt area is bone-on-bone or they have a bulging disc, or the SI is out, or many other deleterious beliefs.

Guess what happens the next time they experience back pain? They’re going to think their disc exploded. That is incredibly maladaptive, and you as a trainer may not have the skill set to coach them out of that, especially because your clients may view you as someone who does not have the medical knowledge base to disagree with the medical practitioner. Now you and your client are set up for long term failure.

All of these reasons that I stated for immediate referral are undesirable. We need trainers who both are comfortable acting within their scope, and understand when a referral is warranted and when it is not. Doing so can rid you can your clients of many of the pitfalls that occur with immediate referral.

When to Refer

I think there are some clear-cut cases in which referring to some type of medical practitioner is warranted.

There was a clear injury mechanism

The first one is when there is a clear injury at play.

Let me give you an example. I had a client who came to me with knee pain. Here’s what he said:

“I was playing football. I had a bunch of bros tackle me, and I heard a pop in my knee. The next day I had swelling and bruising on the inner aspect of my knee.”

I did X, and Y was the result.

Clearly this sounded like some injury happened at the medial knee. My examination suspected a Grade I MCL sprain.

If your client states that there was clear and distinct mechanism of injury—I did X, and Y was the result—then there is a high likelihood that pain and injury are synonymous. A referral is warranted. In these cases, especially an acute injury, could possibly lead to worse problems if left untreated.

[SIDE NOTE: Any out of the ordinary symptoms (e.g. numbness and tingling in the extremities, loss of bowel/bladder function, etc) require immediate medical referral]

The injured area cannot be exercised

Another case in which I would refer out. Is. If there is absolutely nothing you can do training-wise in the affected region.

Many times, you might have someone who has shoulder pain with overhead pressing, but maybe they’re completely fine with a horizontal press. This person may not necessarily be someone to refer out, unless overhead pressing is one of their goals, and your movement skillset (e.g a good lateralization or regression) can’t help that problem. By finding upper body movements that don’t hurt, you may be able to build up tissue resiliency and mobility enough that eventually pain subsides with the next overhead press attempt.

A progression may look like so:

Pushup → Landmine Press → Closed Chain Overhead → Open Chain Overhead

Don’t be afraid to go through that process, and try to find work arounds for someone who is in pain.

If the area affected is so painful that there are no workarounds, then I would definitely refer out. You have no movement options to help that person. In this case. A referral is warranted.

When General Exercise Does not Improve Pain

There are few camps within the physical therapy community that suggest general exercise, (whatever the hell that means) is a useful treatment modality to improve someone’s pain experience.

Is this not the basis of a trainer or a strength coach? If general exercise is a potential solution for someone’s pain, then why can’t a trainer or a strength coach do that? If working out improves your client’s back pain, then you likely do not need to refer them out. Exercise is the solution, and you have the cure.

Improving Variability Improves Pain

I also think that the variability stuff that my colleagues and I perform is utilized with the client (assuming that it’s in your skillset) and pain improves, a referral is not warranted.

I think increasing movement variability is well within the scope of a trainer or strength coach. Maybe you are using these techniques to help achieve positions that a client may not otherwise be able to get into. Maybe you can’t coach them into a deeper squat, but these drills allow your client to squat deeper. No harm.

What if after these drills your client mentions that his or her back feels better afterwards? Do you, as a trainer, think to yourself: “Oh my gosh! I’m not supposed to do that! I need to put their back pain back in and refer to PT?!?” That’s unreasonable.

Sometimes, movement is the solution to our people’s pain. If you can do something—not with the intent of treating pain, but with the intent of improving movement—and it secondarily improves pain, there’s no harm in that. It’s highly likely that your client does not need a referral to the medical provider.

Following the above scenarios as a referral guideline, you’re likely going to protect yourself, and you’re also going to save your clients from a lot of the pitfalls that may occur by dipping into the medical system.

Less Referrals Require Better Coaches

This requires greater demands of trainers and strength coaches. You must feel comfortable working with someone in pain. How can a healing environment for someone in pain be created? It’s ultimately up to coaches to keep clients out of the hands of a joker like me, a medical provider.

Fitness is protective of chronic pain development and can potentially reduce injuries. Medical providers can’t see clients as frequently as a coach can, so it is imperative that fitness is continually reinforced and built.

If a trainer has to refer out because he or she doesn’t feel comfortable working with someone in pain, then our clients will lose the qualities that are inherently protective of chronic pain development or tissue injury.

It’s imperative to reflect upon what you feel comfortable with as a coach, and a clinician. Develop a skillset that allows you to work around potential injuries, and also work on effective collaboration with medical providers. This combination gives your client the best fighting chance of getting over a painful experience and preventing chronic pain.

When someone is in pain, you should continue to train them as normal, but find work arounds that do not perpetuate pain.

I tell all of my clients that I do not want their pain reproduced while I’m working with them. Pain can become a learned behavior with movement. If it becomes a learned behavior with movement, then we can’t get clients back to moving the way we want to. I am not a fan of no pain, no gain. I want them to move safely. I want them to move effectively. If they’re experiencing pain during a movement, there’s likely something that needs to change.

Developing Workaround for People in Pain

Suppose a movement is painful. Before you go and utilize a different activity to achieve that same goal, I would first try to cue the individual out of pain. For example, you may have someone who is split squatting and they begin to complain of knee pain. Upon careful inspection you realize that their knee is caving in. They exhibit valgus collapse.

Instead of throwing the baby out with the bathwater and trying a different exercise, you may just want cue the client to center his or her knee over the foot, keep heel contact, and shoot the knee forward. Those cues alone may eliminate pain during the movement.

If you could cue them out of pain, 1) that’s going to show client that this is not something that is set it stone, but something within their control; and 2) you won’t have to regress the movement.

Sometimes you can’t cue people out of pain. All that means is building your movement Rolodex with other exercises that can achieve similar goals as the offending movement, but are less threatening to that individual.

If we go back to the split squat case, perhaps trying a bottoms-up isometric split squat could achieve similar goals.

Or an assisted split squat? Or half-kneeling exercises? Can you do anything that’s going to achieve similar adaptations as the split squat pain-free? if you can, then you’re still building fitness and now you have a work around.

There are many ways to skin the proverbial cat. I don’t care what activity you use, just as long as the cat gets skinned.

Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic exercise is also incredibly helpful in people having pain. There is some research (here, and here) supporting that aerobic exercise can increase pain tolerance and possibly lower pain. For fibromyalgia, aerobic exercise is one of the de facto treatments for fibromyalgia.

Shifting from heavy strength-based work towards more aerobic methods—whether it’s bloodflow restriction training, tempo method, cardiac output—do something that gets the heart pumping. This activity will help the body release its normal pain-relieving chemicals into the affected region, and theoretically reduce pain. Upping the aerobic contents of the training program can support the pain relief that you are seeking out for your clients.

Collaborating with Referral Sources

Now sometimes you can do everything right, and you still have to collaborate with a medical provider. Maybe you or movement aren’t the solution, and that’s okay. Sometimes this happens. We just have to minimize how often that happens and make that happen when it’s appropriate.

This involves careful dialogue. First, you have to pick the right practitioner to work with. Someone who understands what you’re trying to do, and you must understand what they’re trying to do. You have to work with someone who you can effectively collaborate with. If you and the clinician are speaking different languages, and that will only lead to bickering, poor communication, and the client is going to be negatively impacted. There has to be open dialogue.

When you open up that dialogue, do not use language would make the practitioner defensive. If you start talking about certain concepts that practitioners is not exposed to, they’re going to go on the defensive. They’re going to think that you’re cocky, they’re not going to listen to what you have to say, and they’re going to try to tell you what to do because they’re going to protect their own egos. That’s just how people work. That’s normal.

What instead you have to do if you don’t have someone who thinks like you (I always advocate for working with someone who thinks similarly to you because it makes the communication process easier, but sometimes due to location this cannot happen), you have to speak to them in their language so they understand what you are trying to do. That way, you can encompass all of the needs that your client has when it comes to reducing pain.

If you are thinking ribcages, breathing, and how that influences shoulder position, consider not mentioning that early on if the clinician doesn’t use those methods. Instead, you may mention that “you want to do some things that will improve thoracic spine mobility and build fitness in the upper body, so you’ll try moves that the client was able to perform in the past that didn’t hurt. Are you okay with that? Is that reasonable?” Very rarely will someone tell you that you’re unreasonable, and if you speak in a less technically-intensive language, then you can stay on the same page even if you are approaching the problem from completely different lenses.

An important piece of the rehabilitative process for your clients is making sure that you have effective, egoless communication with any health care providers that you may be collaborating with. If you can do that and maintain a safe healing environment for your clients to get out of pain, then you and your client win. And they will get better.

Sum Up

Referring out or in is a carefully crafted decision, dependent on multiple factors. If you understand when referral is appropriate, you can act in the best interest of the client.

To summarize:

- Inappropriate referral can perpetuate negative pain beliefs, does not mean the client will not have pain, and can create maladaptive beliefs towards pain.

- Referral out should occur if there is a clear mechanism of injury

When do you refer out? Comment below to let us know

Photo Credits