Table of Contents

Is your torso posture limiting your movement? Here’s what to do about it!

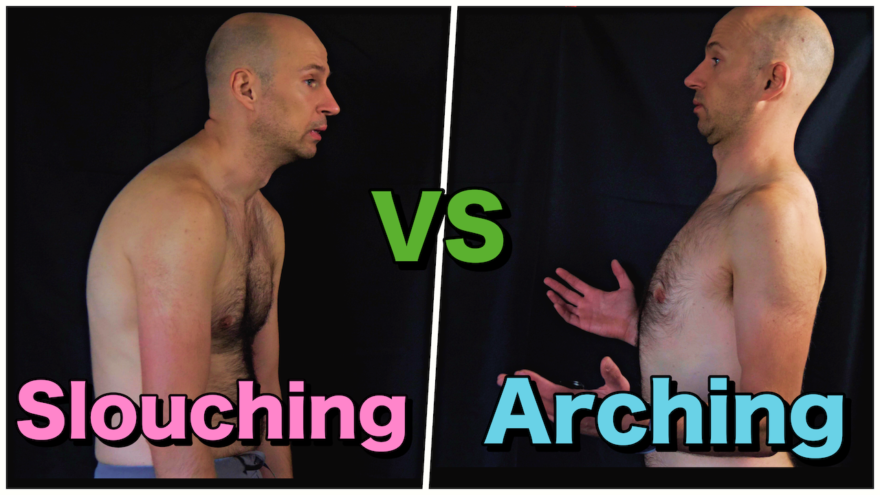

If you have a tendency to be slouched, arched, or anything between, you might be wondering how you can improve the movements that are often lost with these presentations.

The hard part is that the motions limited with these postures, as well as the “fixes” to improve these restrictions, are far from intuitive.

Until today.

It’ll all be cleaned up in Movement Debrie Episode 165.

Show notes

Thorax compensatory strategies

Answer: The strategy in the above question illustrates the difference between the relative segmental motions that should occur with quiet breathing versus the body changing its orientation as a compensatory strategy.

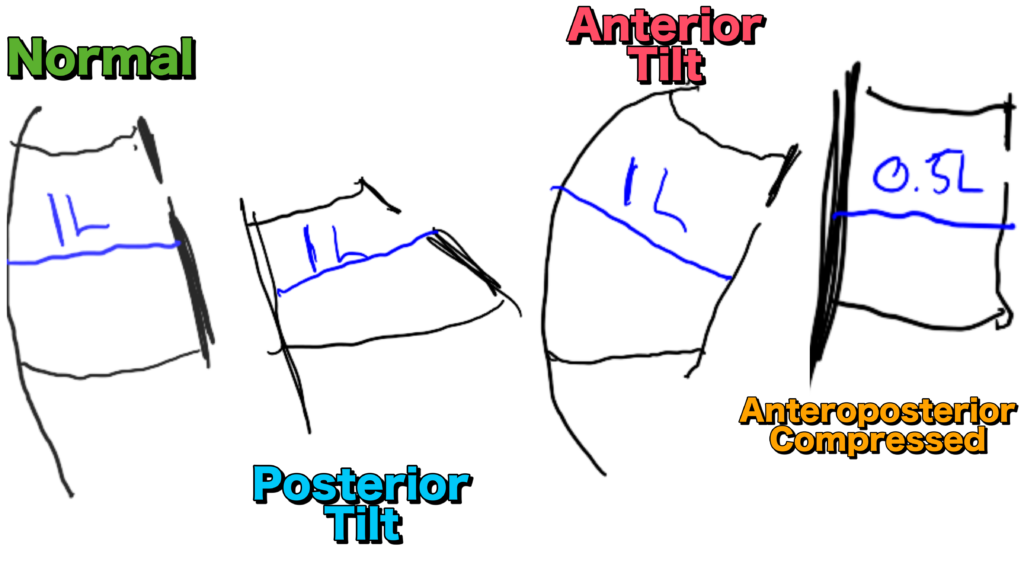

During normal, quiet breathing, the movements of the ventral cavity are quite small. The ribs move apart albeit minorly. The spine and sacrum will move posteriorly albeit minorly. The entire ventral (thorax, abdomen, and pelvis) cavity will expand in all directions albeit minorly.

The key is minor. When I am quietly breathing, I don’t hit an extreme motion one way or another. Extreme motions require more muscle activity. When I am trying to make more space for air, I need less muscle activity. Heck fam, most of the exhale occurs from passive recoil of the diaphragm.

What I think leads to confusion is the limitations of the models we use. When I use a pelvis model, it swings every which way. When I demonstrate ribcage expansion, I may make the motion exaggerated to get an idea of how things should move. But in reality, the amount of motion that ought to occur is diffuse and small.

Think of the models to demonstrate mechanics like reverse maps. Your map app that you use on your phone is a small representation of how big the streets are. Bone models are the reverse of that. We are using big motions to represent small actions, making it easier to see corresponding muscle actions.

In the above instance, relative motion between the joints ought to be preserved. You’ll have “normal” ranges of motion present across all joints.

Which, fam. Is hella rare.

The examples that Gail mentions are progressive compensatory actions. The big movements that she is feeling and the core squeezing/high pressure is a result of progressively increased muscle activity. This activity will lead to a reduction of joint range of motion across a broad spectrum.

Though we cannot say why each of these strategies may happen, what they do allow for is a particular movement to occur when relative motion is not present.

When I have these compensatory strategies, you will not be seeing the multidirectional expansion and compression (getting smaller) that you would see when there is full motion available. You’ll see other wild and crazy things.

Here, we will talk about the strategies that Gail mentions, how each presents, and what the heck you can do about it!

They are:

- Posterior thorax tilt

- Anterior thorax tilt

- Anteroposterior thorax compression

Let’s dive into each.

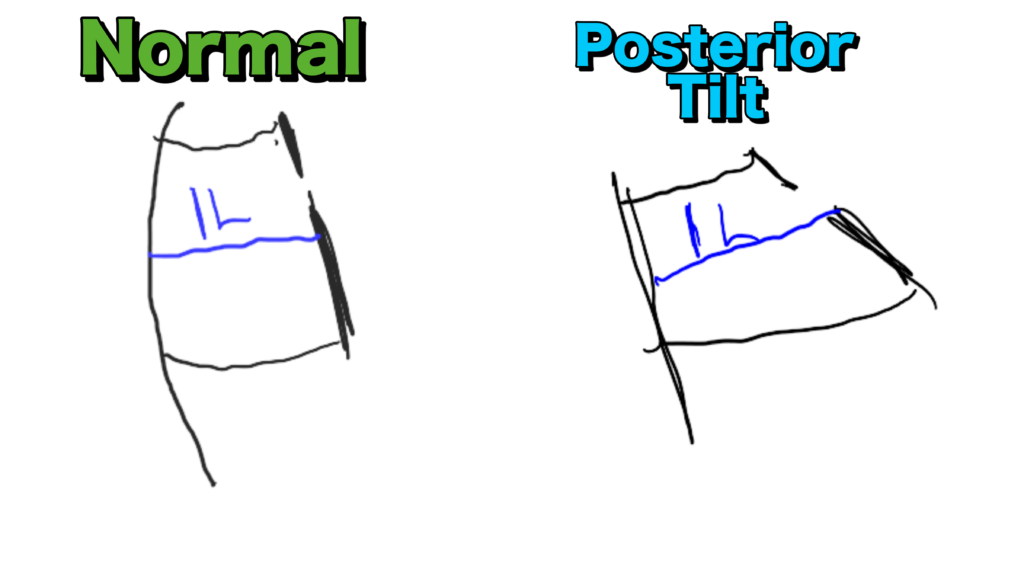

Posterior thorax tilt

A posterior thorax tilt is when the thorax tips backward as a unit.

The sternum will appear to be upward (up pumphandle), and you’ll see the upper back be behind a person’s pelvis.

The upper back often appears flattened in this individual.

How can you confirm though, fam? You have to look at testing.

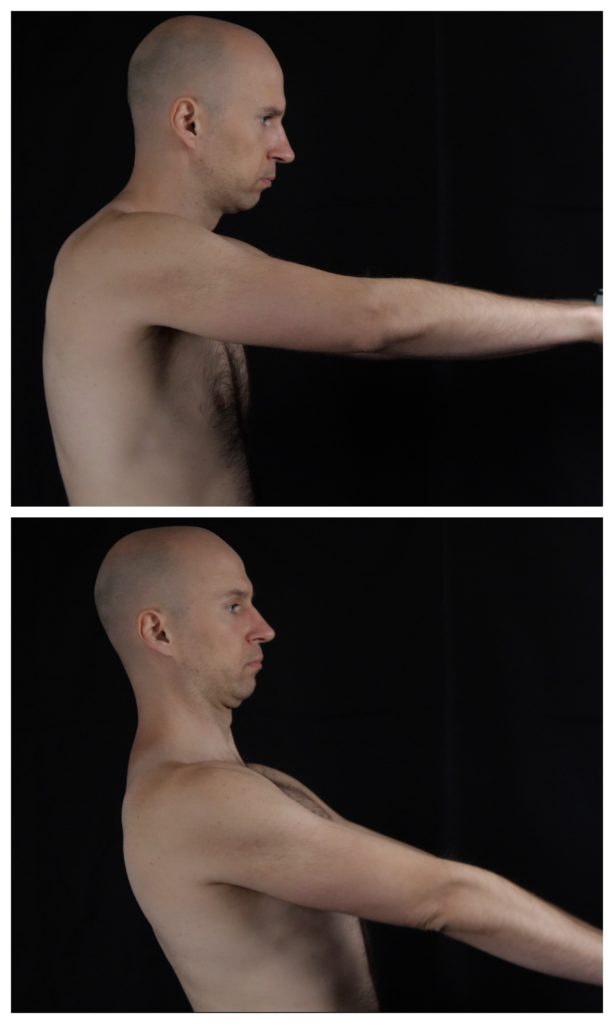

Because the thorax changes its orientation, the relative position of the glenoid will be altered to give an appearance of greater external rotation.

This increased range is DANG DIRTY LIE, though. As there will still be some actions that have an external rotation nature that cannot occur because of the altered thorax action.

Typically, here is how testing will present:

| Relevant Tests | Finding |

| Shoulder external rotation | Magnified, increased (often beyond 90°) |

| Shoulder internal rotation | Limited |

| Total arc of rotation | <180° |

| Shoulder flexion | Limited |

Treatments for posterior thorax tilt

Even though external rotation measures appear to be more, you have to recognize that it’s an illusion. You have to look at what musculature is tipping the thorax backward.

If I’m moving backward into extension, then the musculature has to be on the back, meaning the posterior musculature is concentric or short.

So, big fam, you have to reduce muscular activity on the backside. You have to chase posterior expansion.

Now the problem with some of the classic low reaching activities with this particular population, they will have a tendency to tip backward as they reach forward. Commonly, they are ones who will look like they’ll never get a full reach.

One way to minimize this tipping backward is to perform low reaches in the supine position. The ground will essentially limit your supreme clientele from falling backward, and gravity will assist the posterior expansion here. Bending the elbow will also shorten the lever arm of the reach, making the reaching action easier.

Once you’ve taught them to perform a supine version, you can work towards bent-over connect activities.

The reason why I’ve been liking these as of late is that it takes into account the pelvic posture often associated with these peeps, a sway back posture.

With this particular population, you have to pull the pelvis backward to some extent. Otherwise, the tucking action we perform with the stack will merely push the pelvis more forward.

Moreover, hinging these moves essentially has your peeps performing the reach against gravity, which makes it SUPER HARD to tip the thorax backward.

I’d start with the same connect:

Then work to the cross connect:

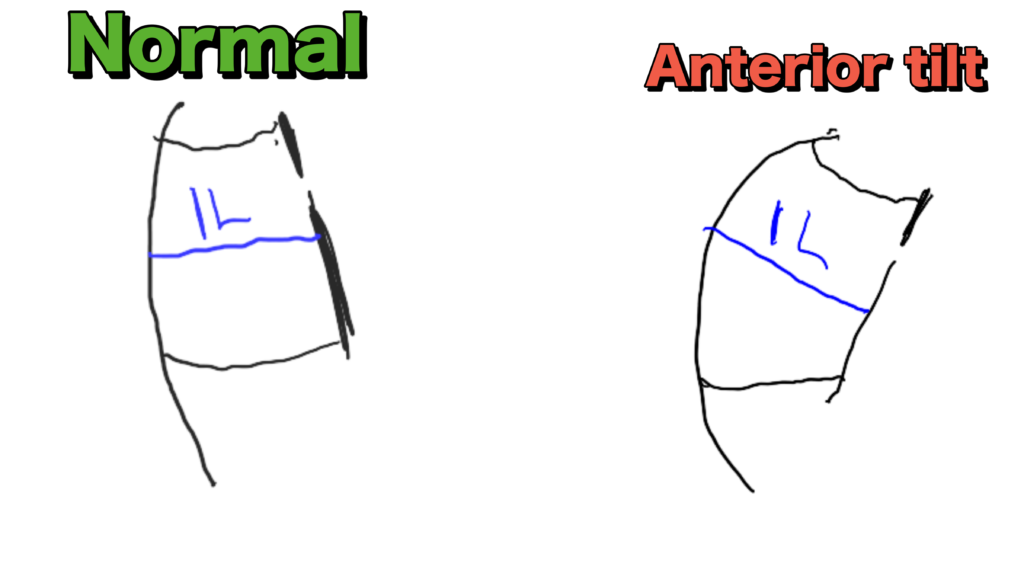

Anterior thorax tilt

As you can imagine, an anterior thorax tilt is when the thorax tips forward as a unit.

The sternum will appear to be downward (up pumphandle), and you’ll often see a forward head posture

The upper back often appears rounded in this individual.

The tilt in this particular individual changes the glenoid orientation in a way that magnifies internal rotation.

Testing presents a bit differently than our posterior thorax tilt peeps. Let’s check it out

| Relevant Tests | Finding |

| Shoulder external rotation | Limited |

| Shoulder internal rotation | Magnified, increased (often close to or beyond 90°) |

| Total arc of rotation | <180° |

| Shoulder flexion | Limited |

Treatments for anterior thorax tilt

Just like with the posterior thorax tilt, we have to take the counterintuitive approach with this presentation and expand anteriorly.

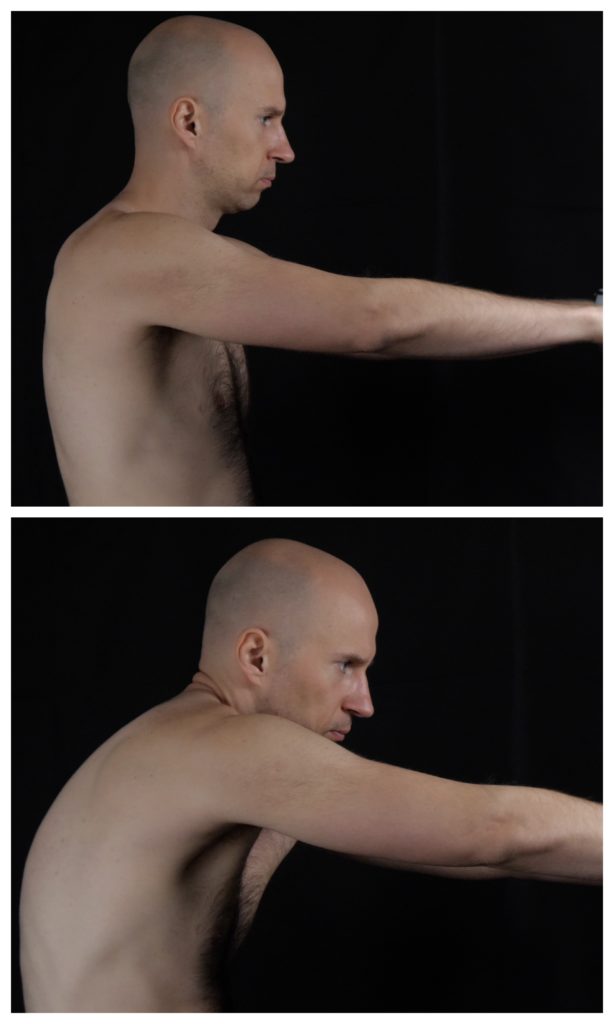

Here, I’ll help you out by learning from my mistakes. YOu ever have someone who has a loss of external rotation, yet when you attempt the low reach with this particular person, they keep overengaging their pecs? Overpecing it, as I like to say. You know, they reach and they crunch:

I have a guy like this right now. Whenever we do stuff to loosen up his thorax, his internal rotation cleans up masterfully, though external rotation loss is fairly significant (like 30 degrees total, he’s stiff fam).

I kept making the same mistake over and over again by having him do low reaches. His neck would freak out, pecs would overengage, and getting an upper back stretch is but a dream.

Yet for some odd reason, he does just fine with landmine pressing variations. Why?

The reason why, fam, as I bash my head into the wall, is because reaching at higher angles allows him to expand the anterior thorax, which is what this type of person needs.

If the pump handle is down, you gotta bring it up. You have to teach these peeps to reach without crunching.

Much like with the posterior tilt, we need to use gravity to our advantage in the beginning. Prone-based exercises are a great starting point, encouraging your supreme clientele to reach without crunching.

Some of these positions from my DNS days might actually be useful as well:

Once you’ve gotten some basic capabilities of reaching without crunching, then you’ll be progressively working towards overhead pressing. I’d start with a landmine press:

Eventually working towards more overhead variations, like an alternating Arnold press:

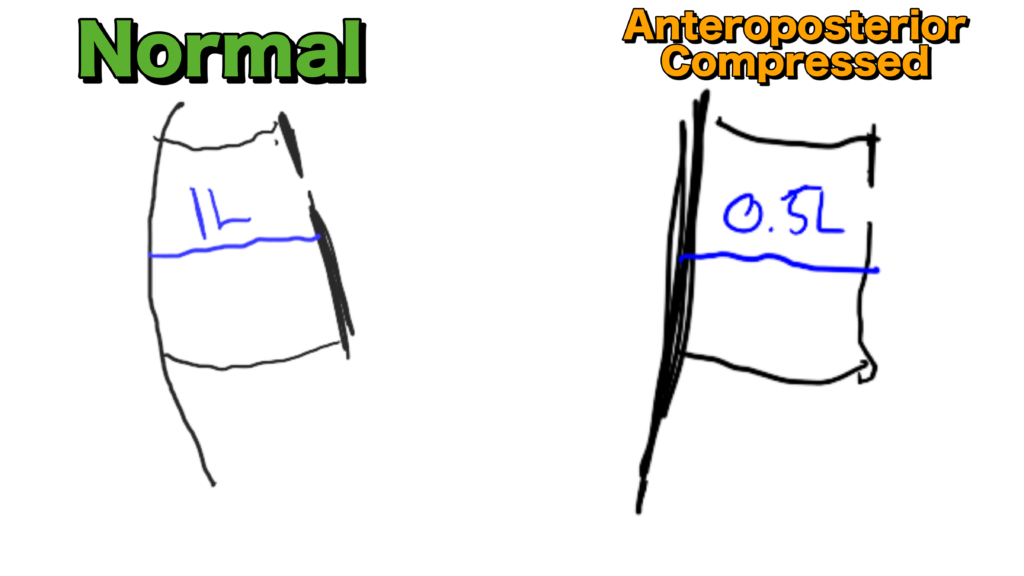

Anteroposterior compression

If posterior thorax tilt happens when the backside gets limited, and anterior thorax tilt occurs when the frontside gets limited, then anteroposterior compression would be a combination of the two.

The presentation here can vary depending on the degree of limitation. But generally, the ribcage dimensions will appear limited front to back and wider side to side, almost oval-shaped.

Here, you’ll see a progressive loss of range of motion in all directions.

| Relevant Tests | Finding |

| Shoulder external rotation | Limited |

| Shoulder internal rotation | Limited |

| Total arc of rotation | LOL |

| Shoulder flexion | Limited |

Treatments for anteroposterior compression

When you have someone who is limited in all directions, there is going to be increased muscle activity and limited space to move into.

For these peeps, you have to create space somehow. Dynamically, your best option is to teach these supreme clientele to move with as little tension as possible. Here, rolling activities are great starting points.

I’d be messing with pelvic rolls in the beginning:

And rib rolls right after that:

To coordinate the upper and lowers, you can then throw in the combo rib and clamshell roll:

Once you reduce that initial layer of compensatory activity, you have to see how the body shakes out. Even though this individual is limited every which way, they still may have somewhat of a predisposition towards a posterior or anterior tilt of the thorax.

The way you can tell which way their bias will go will match the objective testing we saw in the previous cases.

If someone’s internal rotations get full but external is still crazily limited, you may have just allowed them to tilt the thorax anteriorly. For them, you could go with many of the strategies we listed above, or you could go sidelying to be on the safe side, as the sidelying position will help bias anteroposterior expansion according to SCIENCE:

Same with someone with a posterior tilt. If you see this presentation, you could use sidelying for the reasons discussed above:

Sum up

There you have it, folks. Some of my major keys to treating various thorax compensatory strategies.

To summarize:

- Posterior thorax tilt involves a pseudo magnification of external rotation, and is improved with driving posterior expansion in hinged positions

- Anterior thorax tilt involves a pseudo magnification of internal rotation, and is improved with driving anterior expansion in both prone positions and with progressive overhead motion

- Anteroposterior thorax compression involves multidirectional limitations. Activities that teach the client to move with little tension are a great starting point, followed by sidelying activities biased towards wherever limitations persist.

Are there other weird thorax compensations that I missed? How do you deal with these movement limitations? Comment below and let the fam know!