- Where does variability training fit when chasing fitness?

- What do certain variability tests theoretically look at, and what are the relevant mechanics?

- How well does variability training transfer to higher level activities?

- and many more

Table of Contents

Modified Transcript

Charlie: I’m always looking for people to to audit my own thought process on things and help with shifting my paradigm.

I’ve had these conversations with Joe Cicinelli regularly about interjecting PRI-based things with with fitness. It’s not even PRI, it’s just looking at like the body with this neuro-pulmonary/neuro-mechanical lens that I want to move towards and understand more of, but I’m also a pragmatist. I want to be as practical as I possibly can within the context that I’m working.

That’s always a challenge. How do we take this information and make it as practical as possible?

I’ll start with a confession first. I don’t I actually have a strong prejudice against PRI clinical exercises. I just don’t like them in the context of what I do. I’m not saying that they’re bad exercises. It’s either I’m not good at coaching them or I don’t get where they lead to from a terminal endpoint kind of thing. I know what that means to X in a movement in a movement scenario, and so what I’ve been trying to reconcile with myself is how do I get PRI objective test changed potentially with with other things in the gym?

How can I at least identify some things that I either need to regress or refer out to, or how do I know when I’ve hit my key indicator to go to the next thing.

When to pursue variability in a fitness context

Charlie: You talked about looking at variability as a training construct, and so I’d like to get your thoughts on when in the training scheme would you pursue variability as a primary goal?

Let’s say we took a year training program. Would say “maybe I’ll work on restoring some variability in the offseason for an athlete?” for example. Or another context can be I’m gonna try and restore some variability for a new person that comes to see me, and they’re really really stuck, and I want to see if I can restore some variability first before I pursue the power and capacity stuff.

What are your key performance indicators? I know you mentioned in your podcast like active midstance test

and the Copenhagen adduction test

Historically, I’ve looked at things from a very simple, almost mechanical or orthopedic kind of way. I’ll assess clients by going through all of their joints independently, and see if they have range of motion. If not, I apply a local input such as isometric stretching activities or whatever. It sometimes can create changes, but they don’t always stick.

The thing that’s been a game changer for me with looking at things through the PRI lens is addressing the respiratory stuff—looking at rib cage and infrasternal angles—has probably been the most helpful for me. Especially with restoring overhead motion, which as a personal trainer is really valuable for me.

I can clear a lot of shit off the table because I don’t have to do as much foam rolling or isometric stretching or whatever if I can just get somebody to feel their ribs move down, and then start moving their arms overhead while they’re anchoring.

What’s been great as I’ve been able to get rid of a lot of this stuff that I don’t need anymore, but I want to continue on that path and continue to hone that in.

Zac: Become more efficient. I get it.

Now are we assuming you’re not working with someone in pain?

Charlie: Yes.

Zac: Okay. Because for me, that’s [painful states] when this variability stuff is primo.

In the setting that I work in currently, I only chase my objective testing insofar as their pain-free, because eventually I want to give them the stuff you’re doing—squat, hinge, push, pull, single leg, split, power, capacity—and the sooner we can get them to that, the better.

When you’re looking at it from a training standpoint, I worked with a few people on my upcoming product who weren’t necessarily in pain, and then you’re asked the question: “what is what is the use of this variability stuff?” And it’s really idiosyncratic to what extent you need to chase this with someone.

What I would say is you need enough variability insofar as it allows you to use your entire movement repertoire necessary to meet your goals.

For example, let’s say you have someone who can only squat a quarter of the depth, and no matter how well you coach beyond that it is just not happening. Maybe it behooves you then to see if you can eliminate variability as a potential rate limiting step in that equation. Chase down that pathway and then keep using your squat as your marker.

You may get that person to squat deeper than normal, but it still looks terrible. Maybe you have enough variability to where you could coach them into the right position.

Charlie: Talking about whether or not a person is in pain is still a valuable conversation to be had, but I look at PRI is a way to improve a position or to understand why I shouldn’t jam a bent nail into something that’s just not going to go in.

For example, if they’re getting into a half kneeling stance, and they can’t get into their hips or their unlevel in their pelvis because they can’t adduct past midline. These are all valuable things to be able to look at, and then be able to validate with either a table test if I need to, but then look for activities I can use to get them into a position, or help them to feel a position if they have the patience to do it, or we have the bandwidth to be able to start to do that.

Variability Testing and Mechanics

Charlie: The tests that I’ve been using that have been most helpful is looking at infrasternal angle, adduction drop [ober’s test], and shoulder internal rotation. I picked these three to keep it simple for myself; just collecting data and not even telling my clients what I’m doing. If I don’t really know what it means, I can’t really tell you what we’re gonna do; I just want for my own edification.

I want to start collecting and seeing patterns, and just see what changes. Just start observing if what we’re doing is actually changing things.

I don’t do a lot of the other tests, and I don’t know if I should or not I just. I feel like those are the ones that I picked out that would be a good place to start.

Zac: What lead to pick those three tests in particular?

Charlie: Messing around with like shoulder stuff, getting the ribs down has changed shoulder flexion and internal rotation for so many people. That was my first aha moment.

I’ve also seen people where those tests change when they’re under high stress situations.

I had to get better at the adduction drop because I think it was a little bit more setup involved with that for me, but that’s probably the most ambiguous test for me as far as where it drives my decision-making.

Zac: So then Charlie, what do those three tests tell you individually? You see infrasternal angle presentation X, what does that mean to you? When you see a limited oObers test, what does that mean to you? When you see shoulder internal rotation, what is it assessing for you?

Charlie: I think the Obers test tells me the infrapubic angle and how much extension they’re in. And I feel the same way about shoulder internal rotation; tells me how much extension or extensor tone that they might be in. It just tells me what level of stress they’re under.

And I understand that from the PRI perspective that if they’re lacking shoulder internal rotation that it can tell you about ribcage positioning. I conceptually get that to a point, but to me what it means is they need some more activities that get some more rib control or a zone of apposition, and that’s where I stop.

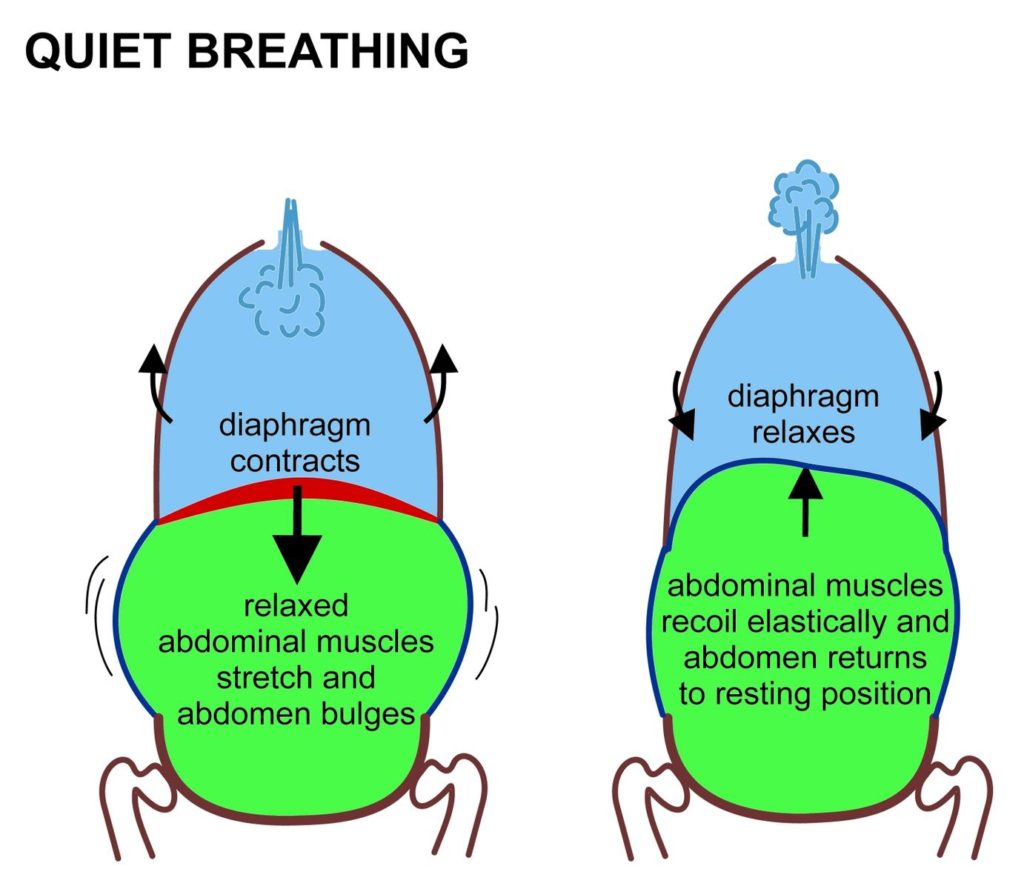

Zac: I would argue that really all three of those tests are proxy measures for a phase of respiration. There’s a certain phase of respiration that’s associated with a wide infrasternal angle. There’s a certain phase of respiration that’s associated with a narrow; secondary to what what we think the diaphragm is doing.

There’s a certain phase of respiration that’s associated with a limitation in internal versus external rotation. Both of those tests have to do with location, and have to do with ribcage mechanics during respiration.

The Ober’s Test also tells you a little bit about respiration, because we know that there are certain things that the axial skeleton does as you breathe in and out along with the ribcage. You could have a limitation in the Ober’s Test or frontal plane adduction with both a wide and a narrow infrasternal angle, and the reason why the Ober’s is limited is because of an anteriorly tipped and forwardly rotated innominate.

However, you can have a relative posteriorly rotated innominate, but because of what’s going on at the axial skeleton, you can still have a limited Obers.

Charlie: I think you mentioned that and I don’t really understand that, but I’ll go with you on this.

Can ask you one side question before you continue? Is it always true that infrasternal and infrapubic angles match? For example, can you see a wide infrasternal angle with a negative Obers?

Zac: Typically, the infrasternal and infrapubic angles should match, and they do match because of what happens with pelvic floor in the respiratory mechanism.

But the reason why you are getting a some people who have a negative Obers coming in versus a positive overs despite the same angle presentation. It has to do with what happens at the axial skeleton above.

As the sacrum nutates, you get a relative posterior rotation of the innominate. As this occurs, you would reason to believe that this would lead to a negative Obers because you are able to clear the acetabulum. The sacral nutation opens up the posterior outlet, which also leads to a wider infrapubic angle.

Now what happens if as I nutate, what also goes on above the spine is an increase in lumbar lordosis; an exageration of the spinal curves under normal circumstances. Obviously it gets confusing because you can have people who hinge at particular segments.

As the sacrum nutates, the thorax increases in kyphosis, the lumbar lordosis increases. If lordosis continues to increase, the sarcum appears “flatter,” tilting the pelvis anteriorly despite the relative posterior rotation. This would lead to a positive Ober’s.

Charlie: So what are you saying that’s potentially driving that? The lumbar lordosis is making it appear that way, and that’s what gives you a positive test? Could you isolate out the lumbar spine with other tests?

Zac: I don’t think you can.

What makes this really challenging is that one could hinge at many different spinal locations. All because we know is normal mechanics, and if they’re presenting in this fashion, then we know that something has happened axially to do that, but really I don’t think it impacts decision-making.

The infrasternal angle is the one thing that could be pretty consistent regardless of how you try to compensate at the axial skeleton. The constraints in the thoracic spine correspond with that.

Take a look at this spine model.

the arrow rotating back is the pelvis.

If I were to increase the lordosis, the orientation of the sacrum and pelvis would be tipped forward despite the backward rotation.

Charlie: So to accommodate to gravity they would just increase the lordosis to get their center of mass over their base of support?

Zac: Well, I can’t say why that happened. It’s probably a combination of managing their environment, genetics, epigenetics, how to best manage gravity, best manage all their stressors in their life. We can’t know why any of this was happening.

Charlie: Mars is in the third house in Jupiter, Mars is in retrograde, a sacrum tilts, we know this.

Zac: And then a butterfly flaps its wings.

Charlie: I only do certain exercises based on the lunar calendar anyway so this is my paradigm.

Zac: You got yourself a commercial model there Charlie.

Charlie: Stay tuned for lunartraining.com.

So you can’t always rely on the Ober’s test.

Zac: You can’t rely on visual inspection.

Charlie: But you’re saying it just doesn’t really change your decision-making either, necessarily?

Zac: Correct, because I’m always still going to address the infrasternal angle first.

Charlie: That’s really what I would like to hone in on. Understanding infrasternal angles. Would you think it’s reasonable enough to go after that?

That’s kind of how I look at it in a fitness standpoint. For a long time even before PRI I took DNS courses years ago we talked about the same thing like rib centration and all this stuff, but it’s hugely powerful on the extremities. And you see that with people that are that have good control and awareness of this stuff.

Zac: If if you had to pare it down to the bare bones, you have two frontal plane measures—infrasternal angle and Obers—that you have you can garner a lot of information from. And what you’re doing with the appendages in both of those cases is pretty much the same thing.

Variability in relation to fitness

Charlie: With frontal plane activities, would you not put somebody in a frontal plane situation in the gym unless they could achieve a negative Obers or are you looking at abduction as well or or not necessarily?

Zac: Here’s where I run into problems. Just because these tests are limited doesn’t mean it can’t do what you asked. It doesn’t mean they can’t get in half kneeling or can’t do a split squat.

Think about all the ways that they try to wow you in for class or whatever, and the ways that they’ve made changes on tests. Lance Goyke is a prime example. I’ve gotten him to get full shoulder internal rotation many different ways that had nothing to do with anything mechanically. I had him watching me breathe and then his shoulder internal rotation was full.

Charlie: Neuro trickery.

Zac: Yeah. But also think about it this way. We’re putting these people into weird, contrived positions in some cases; in other cases not. Why couldn’t it be that you put them in a given position, or they just do something by accident, or at random, and that could lead to some physical change in testing that you may not know about because the context was right.

So what’s to say that the reason why or your person can’t get into a split squat despite having positive Ober’s. They could.

The times in which I would say you’re going to this stuff is if they can’t do that and you can’t coach them out of it.

So chase fitness, because that’s what your primary intent is and that’s why they’re paying you the big bucks. But then you use this as a means to give them options to build fitness that they may not be able to because variability is the rate limiting step right right now.

If you’re chasing variability to get more exercise options to choose from, then that’s different.

Charlie: See that’s interesting too because I thought about with conditioning. In a sporting context where you would taper and get very specific to your needs, but of course the higher you chase for the peak of specificity the more you start to lose general motor qualities depending on the sport.

For example, for powerlifting, which is highly sagittal and extension biased, you’re gonna limit your options further than somebody that was maybe a field sport athlete that requires more multi-directional abilities.

How well does improved variability transfer to more challenging tasks

Charlie: My other question for you is when you’re looking at these tests, how are you reconciling that these passive these are actually going to have transference over to an activity for those high motor demands?

Say you recovered shoulder internal rotation, and then they’re doing a hang clean. How are you assuming that they’re even going to have that or what is your reasoning for that? Is it so they can get back to that when they’re done?

Zac: You know you’re not gonna like my answer. Well my answer is I don’t know.

Let’s use the power clean as an example. Suppose I can’t get a change on the table. How do I know that they’re not making that change while they’re power cleaning?

Charlie: Exactly!

Zac: I don’t. I even would question after spending some time in the NBA league, and just seeing what these people can do without having an adequate strength and conditioning background. In terms of how much things below the terminal point transfer is entirely idiosyncratic.

What we’re hoping is to find ways to bridge the gap towards the terminal point. We just don’t know what and where those points are.

Charlie: What I see more commonly is moving from the clinical to performance world is clinical “A” performance “Q,” and there’s no grading up of the continuum from a low level, low load motor control-based exercise up to a power-capacity exercise. There’s a gap usually there where you’re scaling it up, which is where the whole progression/regression thing is important.

How do you go from a sidelying drill, and then move it up to tennis player doing a rotational forehand or whatever it is? Where does your thought process lead you? How do you transfer from a low to high stress environment?

Zac: How do you bridge the gap? Do you need to bridge that gap?

Charlie: Maybe. A definite maybe.

Zac: Can you not bridge the gap by just making sure you manipulate volume and intensity in such a manner that you don’t potentially put that person in harm’s way by doing terminal exercise?

That is a reasonable progression. You did this side-lying activity and we got what we wanted out of it. Let’s just see if we can kick it up a notch and see if you can do this more challenging activity and then we’re just careful with how we dosed that.

But do you need to go from sidelying to quadruped, to low bear crawl, to tall kneeling, and to half kneeling; I don’t know?

When I’m coaching someone I want to get them to the big bad boys as soon as humanly possible. I’ll go to those and then if they can’t do that I need to supplement it with something a little bit lower level to help basically build it up.

Charlie: I think it’s actually easier to do in a gym environment where you’re doing closed chain activities or your closed environment activities where you’re not reacting to somebody on the soccer field coming at you or an MMA opponent. Whereas if you’re lifting a dead piece of weight and you go a little easier in that context.

Zac: In the MMA guy’s case I don’t know how well what we do does transfer, because we can never produce that degree of chaos, that degree of uncertainty, and that degree of forced production with anything we do in a gym.

What’s the statistic? Every time you take a step in running it’s roughly eight times your bodyweight? It’s a substantial amount and then if you also have a 300-pound lineman who’s trying to eat you, there’s nothing we can do in the gym that that can create that transfer.

What would be a cool scenario for me is if you work together with a sport coach like what I was doing a little bit when I was in Iowa in the D-league. One of the sport coaches and I got along swimmingly. He taught me so much about basketball skills, and we had a couple of return-to-play people we worked with where I’d ask what skills does he need to work on, and then I would dose the volume and intensity.

If the player had a technical fault with something that was general quality, for example I had one guy who could not push off during a shuffle adequately after a foot surgery. I had Coach Joe Boylan (my boi) put this guy in as many positions as possible where he had to shuffle to make the play.

If he was having a hard time shuffling, then I step in and coach the technical aspects, immediately put him back in the situation to implement. To me, that’s where you would get transfer.

So if you’re working with an MMA cat, maybe you are the guy who’s helping manipulate volume and intensity within the the drills that would potentially transfer to fights, such as sparring. Though we even question how much sparring transfers to the fight in Vegas. But maybe you can play a role in that; suggest certain round durations that match the energy systems that are needed for fight night, then supplement what deficits you see and reinforce goals during training in the gym.

Charlie: I think it depends on the context of their year. If you’re as far away as possible from their competitive season, there might be some more things you can do there versus….

Zac: Maybe.

Why are you doing that besides just giving them a breather from their task?

It’s an existential crisis I have with our professions. When do we matter?

Charlie:We want to feel useful?

Zac: Right?! We want to earn the money too in professional sports.

Charlie: I was thinking about this with the whole functional training thing and all these activation exercises, and activation drills. When you strip all those away and you don’t have those in an hour-long session, what do you do with people? The answer is you do more fitness things, which is which is really what we should be doing anyway.

You’re either teaching somebody how to move better or you’re increasing skills that they already have by increasing load, speed, complexity, and endurance.

So to me, I don’t know what activation exercises are doing other than bringing their awareness to an area that they might not sense that will funnel into the skill that they want to get better at.

But if they don’t have awareness than it doesn’t matter anyway. It’s not just gonna magically turn on or off. I don’t even know what that means. It’s not a switch. It’s a mechanistic view of what the body is.

You’re either informing awareness of an area or you’re getting after it!

Zac: Muscle activation exercises are probably just fine as a general warm up too. By doing some of these low-level things you’re probably increasing local circulation.

Charlie: I had a conversation on strengthcoach.com where we spoke about glute activation, and we wondered why are we so obsessed with butts. I think the consensus just came out to be that we were creating a dissociation between spine and hip extension if that’s your goal.

Some people just don’t have any awareness of how to separate the two, so maybe you could argue that these glute bridges that you’re doing every workout would help them to feel hip extension with less back extension.

Zac: But when? And in what context? It comes back to context. Will it happen in the deadlift? I don’t know, the knee position is different.

Charlie: And are you training the glutes and hip extension or in flexion or rotation? You have to get closer to the activity that you’re trying to work on, and there are multiple ways to train the glutes.

When and why is variability training a useful tool in the performance realm

Charlie: In the context of a training environment, if you’re using an activity to create awareness, such as by getting into a position where you want them to feel muscles, I could see that being a useful tool pre-workout. Feel these muscles first and then we’re going to use that. And I’m going to continue that conversation as we saunter over to the barbell and talk about deadlifting.

Or for some of these breathing-based activities it could be useful as an off-day scenario. Have the client practice these things as a way of feeling and sensing muscles, or feeling and sensing air in certain chambers of your body that’s help create stability for deadlifting or whatever it is.

That’s where I rationalize the utility of some of these drills; a way to facilitate linking pieces together in a coordinated fashion. Not assuming that it’s going to transfer, but assuming that at least we have some raw materials to engender awareness so that they can go over and hopefully transfer that in the activity itself.

Zac: That’s fair.

Charlie:Thanks for confirming my biases.

Zac: That’s what I’m here for.

Charlie: I feel the same way about the DNS Canon of exercises. It’s just a way of getting into a position and feeling a chain of muscles that you can hopefully transfer to another activity, as opposed to doing a side clam for a hip, a side bridge for an ab, and external rotations for a shoulder. If I get you into a side support and oblique sit, and have you rotate around those two points, you’re going get all three of those things and it’s likely going to transfer over more to single leg stance activities, rather than doing all three of those concentric-based exercises.

Maybe.

Zac: Maybe. It’s probably idiosyncratic. You could say that this might transfer more for one person, but another person maybe not.

This is the most non-answers I’ve ever given. But I don’t think we have to know all the time.

Charlie: It’s like Western Feldenkrais. That’s how I’m looking at it.

Zac: It’s almost like getting our people to meditate to an extent. You’re essentially building some awareness and focus. Especially this day and age where we cannot focus, attention spans are dwindling.

Maybe a lot of this stuff is also just a good way to get someone into a certain frame of mind that you need them in to be able to perform the terminal moves you need them to do.

Charlie: That would be an ideal scenario where someone formally actually spent some time cultivating some inner awareness.

Which is the battle that I think people have in Fitness. You’re in an environment where you have a loud space, and you’re trying to facilitate a learning experience in an environment that isn’t always conducive for people to learn.

Not that I don’t mind hard rock music blasting when I’m trying to deadlift.

Zac: But probably not when you’re trying to find and feel particular areas or with meditation.

Charlie: So meditation is always the answer!

Zac: Not always. I think if you had to pick something, pick sleep first, then nutrition, and then I probably go movement, then wouldn’t move into meditation first because I’m biased as I like movement. I need to keep my job.

Charlie: I had a very good meditation teacher tell me that you should find a level of mindfulness that you gel with, and then start branching out from there. Movement people should start with movement mindfulness, and then eventually you’re going to find value in the things that you’re not good at like a sitting meditation.

Zac: Don’t you think as you’re deadlifting heavy weight, assuming you don’t get too amped up, that that’s meditative if you stay within the moment for a rep.

Charlie: Depends on how heavy it is.

Zac: Think of your traditional bodybuilding workouts.

Charlie: Bodybuilding is different. It’s highly interoceptive, and I think some elements of bodybuilding could be very useful for people for a lot of different reasons. One of them is bodybuilders are really all about mind muscle connection; feeling and sensing things. and it’s also a very simple single joint activity that you can really feel, get a really good burn, get a really good workout, learn about anatomy through bodybuilding really easily, build local muscular endurance.

And who knows more about manipulating nutrition than a bodybuilder?

Variability testing rationale and intervening based on results; utilizing gymnastics

Zac: Do you understand the stuff regarding testing and where to go with some of this stuff?

Charlie: I have my go-to’s. Here’s what my theoretical progressions for restoring shoulder flexion or improve hip extension or internal rotation to allow for a deeper squat.

Everything for me is modeled into how it’s going to improve somebody’s ability to get into a position to load.

I have my go-to’s, and the list is very small, but I’d like to keep adding on to that if I see things change.

Zac: I use very few moves. If you are a narrow, you are likely to get one of five moves. If you’re a wide, you’re gonna get likely of one of these five moves. You can have these baselines and then you branch out from there pending on what the other testing looks like. Or if I have someone who has limited internal rotation, and based on where they went from the infrasternal, then they’re gonna do this.

I don’t think you need much, just stuff that works.

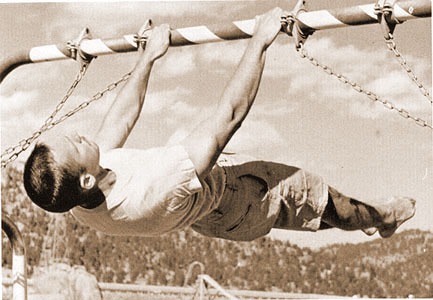

Charlie: Have you messed around with any handstand stuff at all?

Zac: I haven’t in awhile because I got lazy with it. I can only support myself on a wall.

Charlie: I do version called a handstant L-sit where your feet are on a box and you posteriorly tilt the pelvis. It helps keep the ribs down, and get posterior thorax expansion. It’s a better version of a handstand for most people because they’re not going to overextend most of the time. I think it helps ascend the diaphragm by pushing me the visceral contents down towards their head.

I say that because as a wide infrasternal angle person myself, nothing has changed my upper body and shoulders more than handstand work. I have a long-distance swimmer and triathlete right now I’m working with, and strangely enough I have them do handstand work with that and shoulder flexion stuff seems to stick better. My theory is that it is facilitating a lot of things, but also because the handstand has a higher neural demand. you’re putting more body weight on your hands creates a more potent stimulus to the body than doing something open chain.

All this other shit and just I’ve never seen it work, so I just abandoned it and just got them into a handstand. It’s more of a terminal end exercise for shoulder flexion. The changes seem to stick and they seem to last longer.

I don’t like the open chain variations because it’s harder for them at first to control a rib in free space with an open chain implement, like an overhead carry or Turkish get-up.

Zac: What about kettlebell pullovers?

Charlie: I love those. That’s one of my progressions that I use for shoulder flexion, like a hooklying-style pullover, and I do a lot of the hanging work after we do the pullover stuff if I can see they control their ribcage there.

I’ve been playing around different hanging variations, which has been awesome like hanging is by far the best shoulder activity that I’ve seen if they can do it. That’s cleared off a lot of having to stretch a lot of things by just doing those.

Zac: If you can choose intense variations, the body has to respond somehow to it.

Handstand variations sound awesome. I wish it was appropriate for my people, but my people don’t eat vegetables.

Charlie: I can use fitness activities to change positioning, they’re getting a sweat, it’s hard, and they love it. They get some appreciable fitness out of it and if they wanted to do things like overhead pressing. If you can do a handstand, your support function in your upper body is rock-solid at that point.

Talking with friends of mine who have participated in some of these gymnastics-based activities—which is how a lot of our general physical prep was a hundred years ago, a lot of our physical education was born out of Swedish gymnastics and dance, and we for some reason we got away from that physical literacy—the strength elements they get in gymnastics seems to carry over to many more things than traditional strength activities: barbells, dumbbells, kettlebells. It carries over to more of those things. Whereas the other ones don’t necessarily inform the gymnastic skills because gymnastics seems to be a really powerful CNS-intensive activity. Strength is always paired with coordination, and mobility.

Gymnastics is like the Marine Corps boot camp of physical crafts. If you go through that, you can go to any other branch of the service. We can’t say the same thing for the others.

Gymnastics also emphasize a lot of flexion-based activities before extension. I call it “going to flexion-school before you get a job In Extensionville.” Before you get your PhD in extension, you have to learn some flexion. It’s tummy time for adults.

Whereas if you go straight to a barbells you can just extend the hell out of it and get the thing done. But the way gymnastic skills work is if you if you aren’t in a more ideal position, you’re probably not be able to do the skill. Try to do a front lever and not have all this on. Good luck. You’re just gonna fall and look like an idiot.

Zac: It’s what I do every Wednesday when I do my front lever.

Charlie: It’s called “building the glue.” You get to the sticking point, you hold, and then just roll it on the way down.

Zac: That’s pretty much what I’m doing. I can probably make it to two o’clock before I fall.

Charlie: There are several progressions and regressions, and doing the lower level activities, you may be surprised how that helps the higher level stuff. Doing simple things like a hollow rock can help a front lever if you haven’t built some time on doing this basic skill.

Zac: That flies into the face of everything we talked about.

Charlie: Not necessarily. Before, we were talking about open environments versus closed environments. If you’re doing a controlled strength skill in gymnastics, it’s a little different than flipping in the air. We can’t say hollow rocks are going to help acrobatics.

Sum Up

This was an incredible conversation with a dear friend of mine. And boy did he get me juiced up on gymnastic skills.

To summarize:

- Variability is key in painful states, but the need in fitness is idiosyncratic.

- Visual inspection cannot be relied upon in decision-making.

- It is hard to say to what extent any lower level activity will translate to a higher level activity.

- Variability training could be useful in providing context for higher level activities

- Variability training could be a meditative aspect of training for people.

- Gymnastic skills could be a useful fitness tool to enhance variability, strength, and coordination.

Do you utilize any gymnastic skills yourself or with clients? Comment below and let us know.