I want to introduce you guys to one of the smartest fam in fitness, Michelle Boland. She’s a creative strength coach who’s breadth of programming knowledge is second to none.

I wanted to bring her in to the fam because she sent me this dope programming article, which goes over various keys to consider when creating an exercise program.

Enjoy!

Table of Contents

7 Key Programming Variables

Everything is what you make of it. When I sit down to program design for teams many variables must be considered and priorities established. First, there needs to be a macroscopic goal related to a desired outcome. Second, I need to match my approach to that goal. My approach involves the consideration of progression toward the defined goal and the use of specific concepts.

A macroscopic view encompasses the ability to zoom out and establish an overarching goal. A microscopic view encompasses coaching considerations involved within each activity selected, such as cues and rules.

Progressions within the program can also be viewed from both a macroscopic and microscopic view. A typical perspective of progression usually involves volume and intensity. “If a training program is to continue producing higher levels of performance, the intensity of the training must become progressively greater” (NSCA, Baechle & Earle, 2008). Based on this, the progression of a barbell bench press, for example, may be prescribing a greater amount of load, greater number of reps/sets, or greater frequency of the exercise. A regression of a barbell bench press may be a dumbbell bench press or a floor press based upon the reduced load. The focus is placed on the exercise itself. However, there are other (arguable more important) variables involved in progression, programming, and goals of the athlete, for example:

- Do they need to bench press?

- Why do they need to bench press?

- How much movement/system variability do they have?

- Are you considering health or performance components?

- How much body awareness do they have?

- Are they competent in all planes of movement?

- Are you providing them with the ability to transition from 1 leg to the other?

- Are you giving them the ability to have options in their movement or burying them in one strategy for movement?

- Where are you trying to create buy-in and opportunity for personal growth?

These are questions I consider within program design and within progression and regression decisions. It is important to understand the possible consequences of your decisions and the possible strategies that the athlete will use to accomplish the tasks you select.

I am going to take you through a few variables that I consider while making programming decisions. The variables I consider when selecting exercise variations in relation to progressing athletes are explored below:

Health vs. Performance

Health Performance

There is a spectrum with health on one extreme and performance on the other extreme. Health should include an element of performance and performance should include an element of health. When I am programming I am categorizing activities within this spectrum. This can be related to the yin–yang symbol.

The yin-yang symbol can be related to walking on the line of health and performance. You can think of the black as performance and the white as health. Both have an element of each other within them and complement/interact with each other.

The performance category involves motor driven, max effort, dopaminergic (left hemisphere dominated), lack of sensation, high threshold, and limited joint variability activities. Performance activities will need more cheerleader aspects of coaching (focus on set-up position then let them respond) and are programmed in a universal manner. Activities in this category include mostly bilateral, symmetrical stance, sagittal plane activities such as loaded trap bar deadlift or squat.

The health category involves more sensory based, thoughtful, feeling, sense of self (right hemisphere dominated), awareness/feedback, low threshold activities, management of compensations, and aerobic fitness. Health activities will require more teaching, are programmed on a more individual level, and are focused on movement variability. Individualization may just involve different cues for different individuals to feel specific muscles (based upon what they say they are feeling). Activities in this category mostly include asymmetrical, front/back or lateral stances with a frontal and/or transverse plane focus.

Summary

Both health and performance based activities can be progressed and regressed. From the previous example of a barbell bench press vs a floor press: the barbell bench press may fall under the performance category and the floor press may fall under the health category.

Load

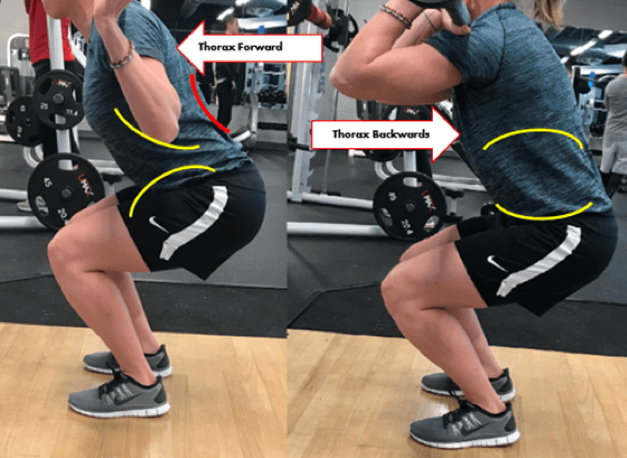

The variable of load can be viewed as numeric (% 1 RM prescription/amount of weight lifted) or as positional placement. I think about the placement of the external load (if required with the exercise). For example, the consideration of the external load during a bilateral, symmetrical squat can be used as a tool to dictate how the individual will manage their center of mass. If I place the weight posteriorly the athlete may need to prevent their center of mass from moving forward by extending via their head, back, calves etc. They may use a posterior joint/impingement strategy (adjacent vertebrae moving closer together) to create stability in this position of loading.

If I choose a cambered bar or a spider bar it will lower the external load to the individual’s center of mass which will assist in its management. The front handles of the spider bar also allow for rib cage retraction via reaching and establishing good set-up position. Choosing an anterior external load may provide the athlete with a greater ability to manage their center of gravity, incorporate reaching, and manage rib and pelvis position. The anterior placement of the external load and proper setup position may allow for a more anterior muscular strategy to move through the range of motion.

During a split squat activity, for example, the placement of external load or external objects can assist in the plane of motion focus. If I program a 1 arm kettlebell load (Ipsilateral 1 Arm KB Split Squat Opposite Reach), the load position assists with the plane of motion focus (in this case frontal plane). If I hold a cable across my body during a split squat, that could allow for a more transverse plane focus. The muscles that the athlete feels working in ‘health’ component activities is the most important aspect of success in these activities. However, consideration of the load placement can assist with the outcome. Load placement can also dictate the strategy used by the athlete during the exercise.

The placement of load is something I consider to be a way to progress or regress an exercise besides the actual amount of load (less important to me). Load prescription can be programmed with Rate of Perceived Exertion 1-10 scale (assuming athletes know what a “1” and a “10” feel like) or velocity based ranges using GymAware or Tendo Unit technology. Velocity tracking technology can provide objective feedback to encourage effort and intent. Repetitions and sets are usually the last thing I fill my program with as I think it may be the least important variable in most cases.

Summary

Progression of load, to me, involves the consideration of the load placement and how load placement can assist with plane of motion focus during an activity.

Planes of Motion

On the spectrum of health vs. performance, activities within the health category may have a frontal plane and transverse plane focus while activities in the performance category may have a sagittal plane focus. All activities are focused on the starting position of the axial skeleton and pelvis. Health activities are very focused on establishing a sensation within the plane of motion then completing the activity.

I like to pair activities together with what I consider to be progressions. For example, if my approach is related to teaching the ability to transition from 1 leg to the other (centering over a stance leg) with a frontal and transverse plane focus, the following would be activities I would select: first exercise in a pairing is a lateral stance cable row & reach, the second exercise is a lateral stance medicine ball throw, the third exercise is a slideboard pause, center, & push (see video below). Each activity selected uses the same concepts but progresses with additional variables.

The type of reaching (limbs moving forward while proximal structures are moving backwards) I program also dictates progression of activity. Both arms reaching forward is focused on rib cage retraction (triplanar) to experience proximal structures moving backwards. A 1 arm contralateral reach may be focused on rotation at the thorax and/or pelvis. Progression would involve the consideration of a unilateral reach; ipsilateral or contralateral reaching can change the focus of the activity.

The plane of motion focus is indicated by what the athlete is saying they are feeling. Cues and external references are utilized to target specific muscles in planes of motion. This concept is very focused on gait biomechanics, such as the phase of gait the activity is focused on and what muscles are felt. Gait biomechanics are incorporated into all activities that fall within the category of health. This is prioritized as it relates to every sport activity, i.e. skating, throwing, or running. It is about the ability to transition from 1 leg/hemisphere to the other and back, center yourself over a leg, and rotate your thorax in the opposite direction of a pelvis.

Summary

Progressing plane of motion is focused on where the activity falls within the health vs. performance spectrum, types of reaching, and the phase of gait being emphasized.

References

References involve information about the environment. References are opportunities for sensory feedback. I can either take references away or add them to progress an exercise. Adding reference may provide more awareness and help with learning about where the body is in space.

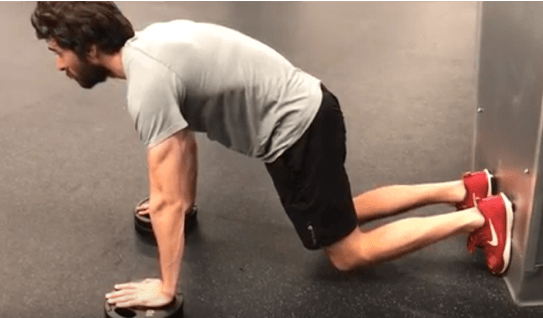

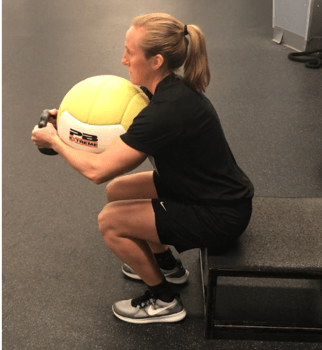

References can either be external objects or awareness of a body part. External objects can include a box behind an athlete while squatting, a ball between the knees to help feel adductors, a wall to place heels, a medicine ball to retract the rib cage, or a band to apply resistance. References as a body part for awareness are considered within the set-up position. Examples of body parts used as references include cueing feet and ribs during squats and deadlifts, cueing heels as a reference for hamstrings, feeling adductors for frontal plane competency, or feeling an ab wall for rotation.

Summary

References, such as body awareness points or external objects can be used within an activity. References can serve to assist in accomplishing the goal of the activity and be used to progress or regress that activity.

Tempos

Tempos to me mean the manipulation of duration. For performance based activities you can prescribe slow eccentrics or isometrics (see Cal Dietz triphasic training principles). For health based activities SLOWING people down is key; prescribe slow, long duration tempos to allow for body awareness and time to think about what they are feeling. For example, prescribing a split squat with a 3/2/2 tempo means 3 seconds down, 2 second hold at bottom, and 2 seconds up. You can also pair similar exercises together to create more awareness.

A trap bar deadlift or a squat can be placed on the spectrum of health vs performance based upon prescribed tempo (also load). The trap bar deadlift and squat can be shifted to the health end of the spectrum by prescribing a slow tempo and removing load. The exercise would be focused on finding and feeling specific muscles, creating awareness during the movement, and making it a low threshold activity; prevent clenching, gripping (remove thumb from grip), and breath-holding.

Tempos can also be utilized for a metabolic/conditioning benefit. Timed sets or slow, long duration activity can possibly create both central (stroke volume, blood volume) and peripheral (increase capillary density and mitochondria in working tissue) aerobic adaptations. For example, programming a squat for a minute duration or choosing resistance exercises for a timed set based circuit.

Summary

Progressions of tempos include consideration within the health vs performance spectrum and metabolic goals.

Rules

Athletes will probably pick up on 1-2 cues, so either have options or use the same ones over and over. Establish the idea that everything we do, is the same thing we do; i.e, a deadbug position is a squat or a bear position is a squat. Carry concepts over to various activities.

You can also consider focusing on the task selected vs. the organism. Create rules for the task/exercise instead of cues for the athlete. For example, rules for a kettlebell deadlift could be keep midfoot on a line, put kettlebell on the line, put kettlebell back on the line, and touch hips to box/wall behind you (credit to Coach Dan Sanzo for this idea). Creating rules may take away the perception that they are doing something wrong to just stating a rule.

Summary

Progression of rules could involve more or less of them depending upon how you view the complexity.

Coaching Tactics

Once I have established a macroscopic plan based on a goal and have organized my approach microscopically with the activities selected, I can now reinforce these decisions with coaching choices. Ask athletes questions: what they think, what they feel, or what option they want to do (when choice is provided). Negative reinforcement is not effective, so be positive. Be a cheerleader or teacher when necessary. Be responsible for a position of influence.

Summary

Align coaching approach, cues, considerations, and behavior with program, athlete, and activity goals.

Conclusion

Progression is related to your program goal and your approach to that goal. It is not just about volume, amount of load, or frequency. Progression involves many variables all related to efficiency of movement and the relationship between health and performance.

It is our job to determine which variables matter more than others but in the end, none of the above information matters if you’re a jerk. The variable that matters most in success of your program is consistent effort by your athletes; which can be impacted by whether your athletes like you as a person or not. So be a good person to whom ever you get the privilege of coaching.

Want more exercise examples? Click HERE for Michelle’s Exercise Database

About the Author

Michelle Boland

- Sports Performance Coach (Boston, MA)

- Exercise Physiology, Springfield College

- S. Strength and Conditioning, Springfield College

- S. Nutrition, Keene State College

- Website: http://www.michelleboland-training.com/

- Follow on Instagram @mboland18

References

Baechle, T.R, & Earle, R.W. (2008). Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Third edition. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.