Table of Contents

How improving tongue mobility can impact sleep and nasal breathing

I hit a plateau.

I was getting good results with many clients. I was making infrasternal angles dynamic, restoring hip flexion and extension, and getting ribcage mobility on fleek.

Yet there were still some folks who I couldn’t get the symptom change they needed. Either they had really stiff necks, craniofacial issues, or difficulty sleeping.

I knew I was missing something.

Then I found myofunctional therapy.

My buddy Joe Cicinelli, my myofunctional therapist, gave me some tongue exercises surrounding my tongue-tie release surgery, and I noticed some interesting changes with myself. My neck felt looser, I was sleeping better, and just overall feeling better.

I decided to experiment and try a few activities here and there on some clients. With having only a rudimentary understanding, I started seeing some of those troubling cases improve.

Necks were less tight. Sleep was improving, jaw pain was vanishing.

I needed to learn more.

That’s when I came across the Academy of Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy (AOMT) and saw they offered an introductory course.

I was in. Four days later, a gap was filled.

Having applied these techniques to several patients, many of those troubled cases were not so troubling. Although I was addressing airway with most of my treatments, I neglected the uppermost portions of it.

The folks at AOMT give you that and then some.

With this course, we deep-dived into anatomy, evidence, assessment, treatment, and business. You really get a total package over the four days.

Most courses I’ve attended give me minor tweaks in practice hear and there, but this one forced me to overhaul many areas of my practice; developing new skills in the process.

Should you take this course? Hell to the yes!

Don’t believe me, then check out the notes below and see for yourself.

What is the stomatognathic system?

Myofunctional therapy focuses on the health and performance of the stomatognathic system.

What the hell is that???

This system consists of facial structures that the maxilla, mandible, teeth, dental arches, temporomandibular joint, and all associated soft tissues.

The functions of this system include:

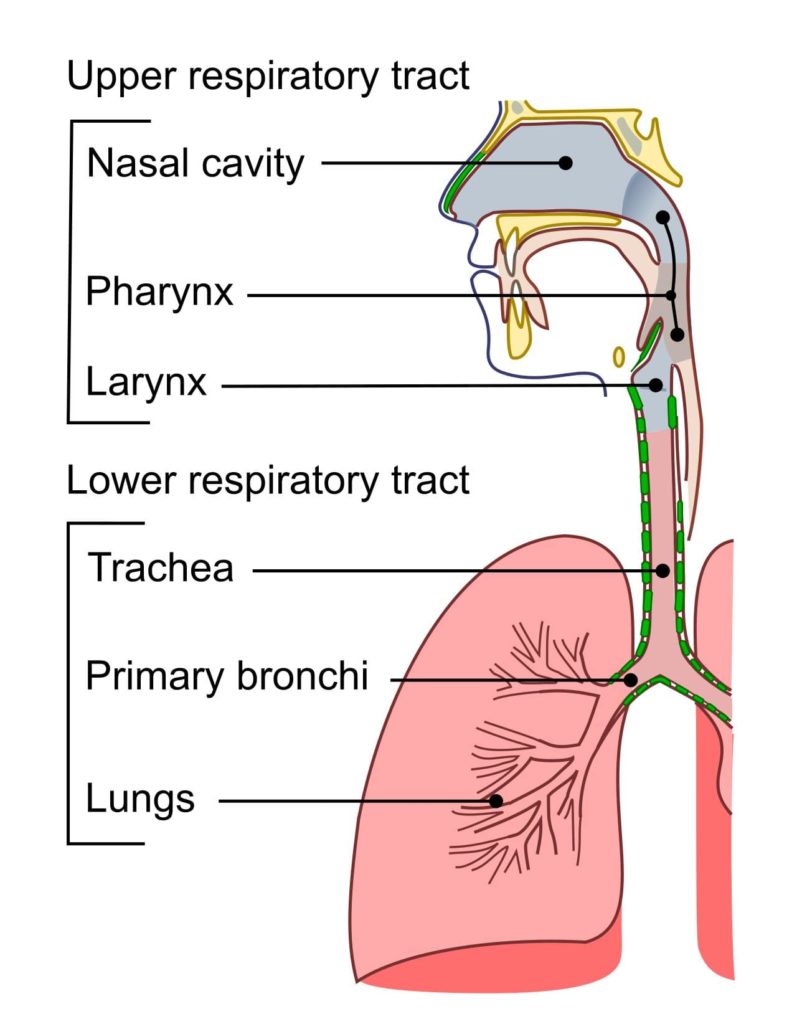

- Respiration

- Deglutition (swallowing)

- Speech

- Olfaction

- Mastication

- Maintenance of head posture

This system’s adaptive functioning can be influenced by one’s resting tongue posture.

Resting Tongue Posture

The tongue is a key player for stomatognathic function. It is a muscular organ that has several functions:

- Increase airway patency

- Suckling and sucking

- food/liquid manipulation

- Swallowing

- Natural teeth retainer

- Oral hygiene

- Articulation and resonance

Ideally, the entire tongue should be placed on the roof of the mouth at rest, with the tip being on the spot where your tongue goes when you say “N.” The soft palate should rest on the tongue or be slightly elevated, with little to no teeth contact. This position, called a palatal tongue posture, acts as a valve for the airway; promoting nasal breathing, and shaping the palate and nasal base. At nighttime, this tongue posture can stimulate growth hormone release.

What happens if you cannot attain this resting tongue posture? Then there will likely be disorders within the stomatognathic system. These issues are called Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders.

Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders

Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders are considered negative functional disruptions within the stomatognathic system’s structure and/or function.

Our skull and upper airway shape have dramatically shrunk since the dawn of agriculture. These changes are likely due to reduced food diversity and softer foods. These foods require less chewing, leading to an inadequate stimulus for facial bone development.

Moreover, a portion of the population is predisposed to frenulum restrictions in the tongue, lip, and/or cheek; negatively impacting bone growth. Restricted tongue mobility, in particular, is associated with maxillary deficiency and soft palate elongation. This drooping downward blocks the airway.

All of these factors negatively affect the upper airway. Namely, it becomes difficult to nasal breathe. Thus, we may have to utilize strategies to intake air another wayーour mouth.

The tongue acts a lot like the abdominal viscera. When movement restrictions develop in the abdominopelvic area, the internal organs are pushed downward and forward. This change contributes to an anterior pelvic tilt.

So to with the tongue. When the tongue cannot be placed on the roof of the mouth, it will rest on the mouth floor and thrust forward. This position narrows the palate and tilts the face anteriorly. In myofunctional terms, there will be increased vertical facial growth.

Causal factors for this growth are unknown, though there may be links to MTHFR gene, allergens, food sensitivity, environmental toxins, air quality, lack of breast feeding/increased bottle feeding, and sippy cup usage.

Signs and symptoms of an Orofacial Myofunctional Disorder

Though orofacial myofunctional disorders can start small, they can lead to major health disorders left unchecked. The health woes associated with these disorders include:

- Temporomandibular dysfunction

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome

- Orthodontic relapse

There are several signs and symptoms that may indicate whether or not someone has a myofunctional disorder. Clinically, you may see things like:

- Tonsil/adenoid inflammation

- Chewing disturbances

- Sleep disturbances

- Tented lip – The upper lip looks like a triangle

- Mouth breathing

- Decreased saliva (which increases periodontal disease)

- Bruxism/clenching

- Maxillary insufficiency – The middle part of the face will appear retruded

- Flat cheekbones

- Septum pulls down and deviates

- Venous pooling under the eyes

- Breaking of the nose (nose bump)

- Flaccid, puffy lips

- Narrow palate

- Tongue scallops – The sides of the tongue will have indents from the teeth

- Swallowing disturbances

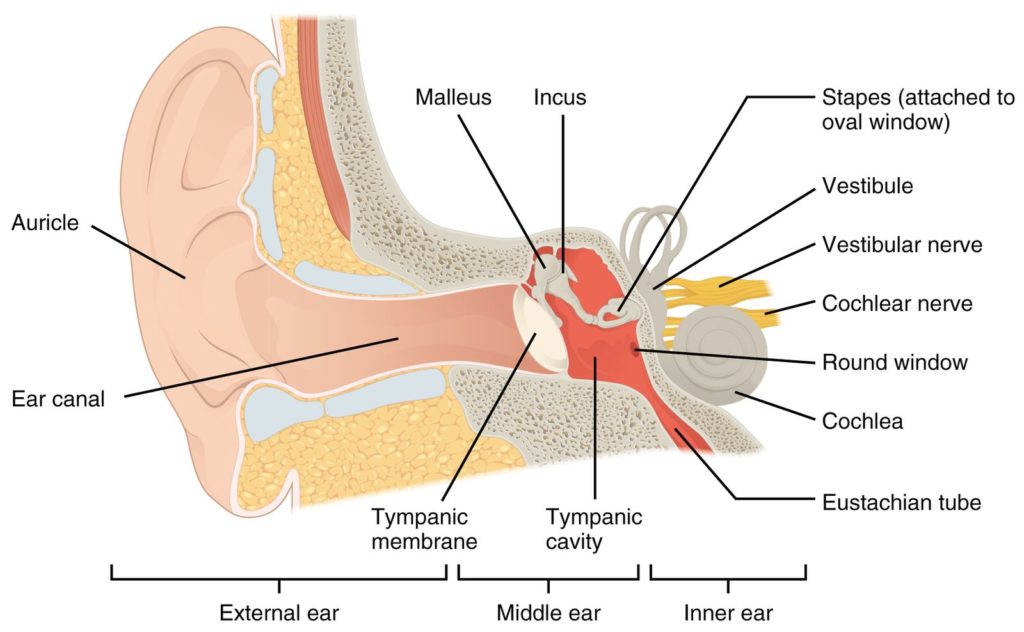

- Eustachain tube dysfunction

- Gummy smile – When one smiles, you see a lot of the gums

Let’s dive in a bit more closely to a few of the key signs.

Chewing Function and Dysfunction

Chewing serves many purposes besides breaking food down. Appropriate chewing improves digestion, pressurizes the outer and middle ear, and aids in facial bone growth.

Surprisingly, chewing can increase alertness and cognitive function. Chewing neurotransmitters work in opposition to those active with sleeping, providing a safety mechanism for accidental choking.

Ideally, chewing should alternate side to side with the posterior teeth (aka the molars), though it is normal to have some unilateral chewing preference. Chewing 30-40 times per bite has been shown to improve digestion. Exposure to various food types and textures can enhance this capability.

On the other hand, soft diets and reduced food diversity negatively impacts bone growth, facial development, eustachian tube function, and increases sympathetic nervous system activity. These effects cannot be reversed even if there is a catch up period from soft to hard diet.

Compensatory chewing strategies may include:

- Excessive unilateral preference

- Chewing with anterior teeth

- Decreased chewing volume

- Open mouth/lip-smacking

- Excessive tongue use

A great way to encourage appropriate chewing patterns is the tube chew activity, which stimulates bilateral chewing.

Swallowing Function and Dysfunction

Swallowing is a fairly complex activity that is broken down into four stages:

- Oral Preparatory: The act of taking food, chewing it, mixing it with saliva, and forming it into a bolus

- Oral: Controlling the bolus and transporting it to the back of the mouth

- Pharyngeal: Initiating the swallow reflex in a timely manner (i.e. 1 second)

- Esophageal: The food enters the esophagus

You’d be amazed at how often you swallow throughout the day. You swallow 500-1000 times per day at 55g/cm with each swallow. That’s equivalent to two tons of pressure per day. That’s a lot of reps, so your swallow ought to be on fleek.

The ideal swallow has the tongue kept on the roof of the mouth with light teeth contact. There will be minimal to no facial or neck muscle activity. The inability to maintain this posture causes a tongue thrust.

A tongue thrust is when the tongue either moves forward against the front teeth (anterior) or outward between the teeth (lateral).

This action occurs to move the tongue away from the airway, making it easier to breathe. If someone cannot nasal breathe during swallowing, a tongue prevents suffocation.

Other swallowing compensations include:

- Open mouth swallow

- Food falls out of the mouth

- Forward head movement

- Bottom lip protrudes forward

- Lips pucker

- Loud swallowing

- Presence of food residue in mouth after swallowing

- Gagging

If you struggle with coughing or choking during the swallow, or food feels sticky and doesn’t move well, these are more impairments in the speech language pathologist’s domain.

Sleep disturbances

Sleep disturbances are fairly common with orofacial myofunctional disorders.

The inability to keep the palatal tongue posture during sleep causes the tongue to fall back into the upper airway. This position collapses the pharyngeal wall, reduces airway space, and may lead to oxygen desaturation at night.

There are two main airway issues during sleep:

Apnea: Airflow cessation for greater than 10 seconds with continued chest and abdominal effort. Associated with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Hypopnea: Decreased air intake amount. Associated with upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS).

Both of these disturbances can be measured on a sleep study.

For OSA, the Apnea–Hypopnea Index (AHI) is used to measure the number of apneic events one experiences throughout the night. Whereas the Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI) looks at arousals that disrupt sleep. These awakenings are often associated with decreased air intake or airflow cessation less than 10 seconds.

Neither of these syndromes are desirable, as their presence can affect a wide variety of physiological functions. OSA in particular has been associated with a decreased lifespan. Whereas UARS can negatively impact deeper sleep stages. Thus, it’s important to screen clients for the presence of these disturbances.

The signs and symptoms that would warrant a sleep study differ slightly for kids and adults. For children, the tell-tale signs are:

- Difficulty falling asleep at bedtime

- Frequent awakening or bedwetting

- Mouth breathing, loud snoring, or excessive movement during sleep

- Difficulty waking in the morning

- Inappropriately falling asleep during daily activities

For all patients, these are the red flags:

- Scalloped tongue

- High narrow palate

- Excessive overjet (top teeth are significantly further forward than bottom teeth

- Low soft palate position

- Bruxism/clenching

- Large neck size

- Obesity

- Allergies or congestion

- Reports of poor sleep quality, fatigue, concentration

- Restless leg syndrome

- Daytime sleepiness

- Frequent awakenings to go to the bathroom

- Snoring

- Dark circles under the eyes

- Missing teeth

The cool thing? Myofunctional therapy has been shown to improve sleep disturbances! This systematic review demonstrated reduced snoring after myofunctional therapy, possibly improving sleep quality.

Bruxism

Bruxism is defined as teeth clenching and grinding. Daytime clenching is termed Diurnal Bruxism, whereas clenching during the night is called Nocturnal Bruxism.

Let’s first discuss diurnal bruxism. Clenching activates chewing muscles. Since these muscles are active during eating, clenching may be a self-soothing way to increase parasympathetic nervous system activity. This strategy’s cost is increased craniofacial tension and subsequent movement option loss.

Diurnal bruxism can also occur with altered disc-condylar relationship at the temperomandibular joint (TMJ). Ideally, a palatal tongue posture helps stabilize the jaw and keeps the TMJ articulating with the disc. A low tongue posture may cause the mandibular condyle to slip off the disc, causing clicking and popping. Clenching can prevent this slippage.

Nocturnal bruxism, on the other hand, may have upper airway influences. If the tongue falls back during sleep, the pharyngeal wall will collapse and the mandible will retrude. These changes reduce upper airway space.

Bruxism acts essentially as a compensatory strategy to open the upper airway. The grinding movement is an attempt to protrude the mandible, opening up the airway. Excessive sleep movement accomplishes a similar goal.

Eustachian tube function and dysfunction

The eustachian tube is a canal that connects the middle ear to the nasopharynx, the area of the airway that involves the posterior nasal cavity. This tube matches middle ear pressure to that outside of the body.

In order for the eustachian tube to aerate, a firm tongue tongue-to-palate swallow and pumping of the soft palate is necessary. If there is poor swallow quality or an eccentric soft palate, inner ear pressurization could be impacted.

Poor tube function has been associated with an increased incidence of abnormal swallowing, tongue thrust, teeth-apart swallowing, lack of sealing off the anterior oral cavity, and increased tone of circular muscles in the face.

Assessing Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders

The assessments taught at this seminar were extremely comprehensive. There are several aspects the myofunctional therapist ought to look at to appreciate the craniofacial system.

While I do not use all of the assessments taught in the course, assessing the following areas has proven useful:

- Facial structure

- Oral cavity structure and function

- Tongue function

- The dentition

- Breathing

Let’s dive into each category!

Facial Structure

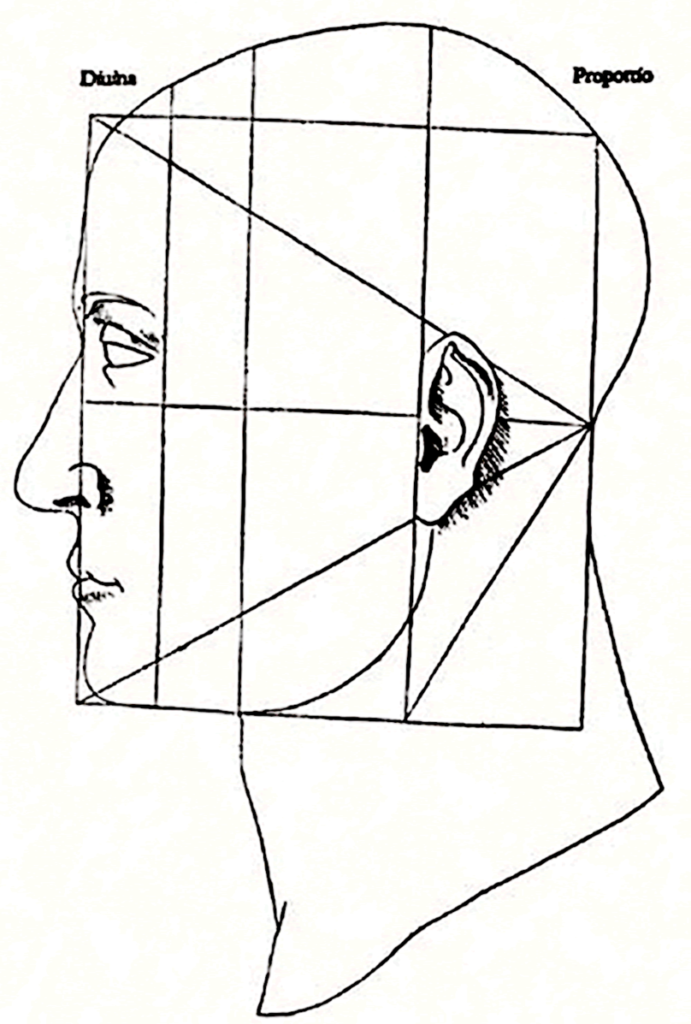

Though we are asymmetrical creatures, proper facial development ought to be fairly symmetrical. If we break up the face into thirds, the top, middle, and bottom parts ought to be about the same distance.

Inability to nasal breathe and attain a palatal tongue postures changes the way our face grows. The primary compensation is increased vertical facial growth (aka an anterior facial tilt), as the low tongue posture drops the face downward. You’ll see that the bottom third becomes significantly larger than the middle and top.

Side profiles can also show vertical facial growth. Ideally, the maxilla and mandible should be well beyond the insertion point of the nose.

Oftentimes, you will see someone present with a retrognathic posture (mandible retrusion):

Or a concave face (maxillary retrusion):

The Oral Cavity

This testing focuses on the oral cavity’s structure, space, and function.

We can break up this testing into the following broad categories:

- Palate Structure

- Soft structures

- Dentition

Let’s look at each

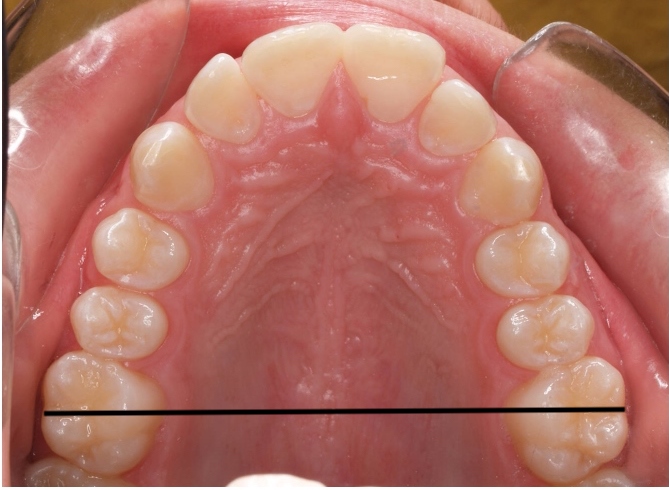

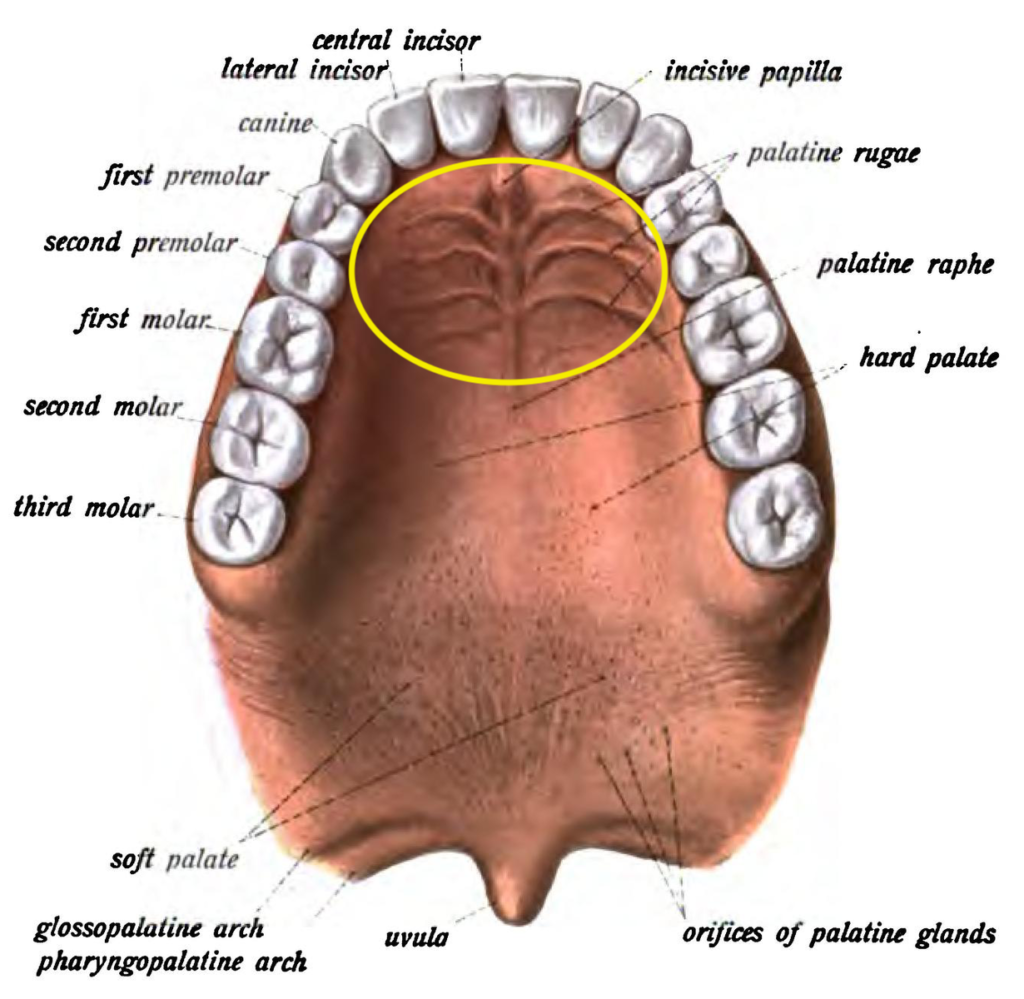

Palate structure

First, we will look at palate shape and pathology.

When assessing palate shape, we will predominantly look at palate width. Normal width ought to be 40-44mm for an adult. The first molar is a good marker, measuring from the lingual edges

When the palate is narrow, there may not be enough space for the tongue to plaster up against the roof of the mouth. The only option becomes a low resting tongue posture.

Surprisingly, this width can change a few millimeters with myofunctional therapy!

It ought to be noted if there are any mandibular or maxillary tori present. These are bony growths that can often form secondary to facial muscle overactivity.

Soft Structures

Here, we will look at the soft tissues that can negatively compromise the upper airway. The key areas to focus on will be:

- Tonsil size

- Soft palate

- Buccal and lip ties

Let’s dive into each

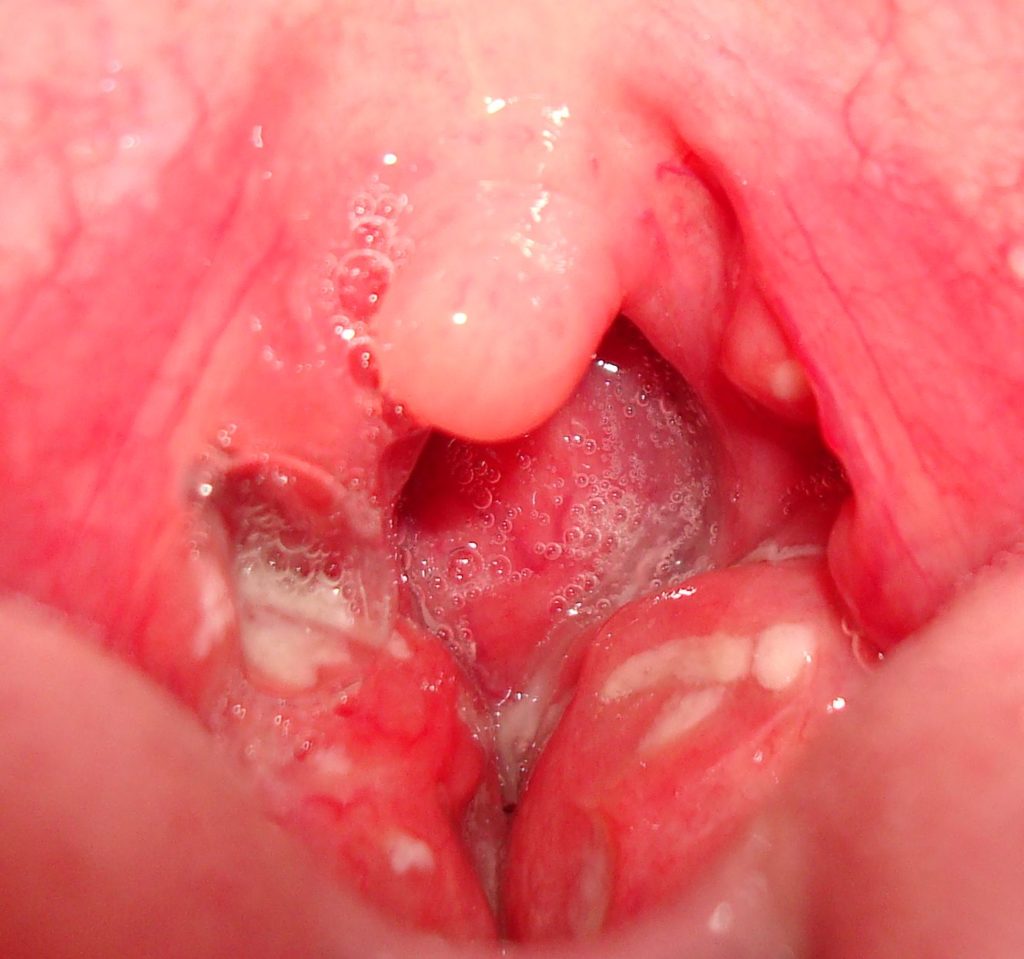

Brodsky tonsil grading

This measure looks at the extent that the tonsils are encroaching on the airway. The percentage of the oropharyngeal space occupied is described as follows:

- 0: surgically removed

- 1: <25%

- 2: 25-50%

- 3: 50-75%

- 4: 75%+ (kissing tonsils)

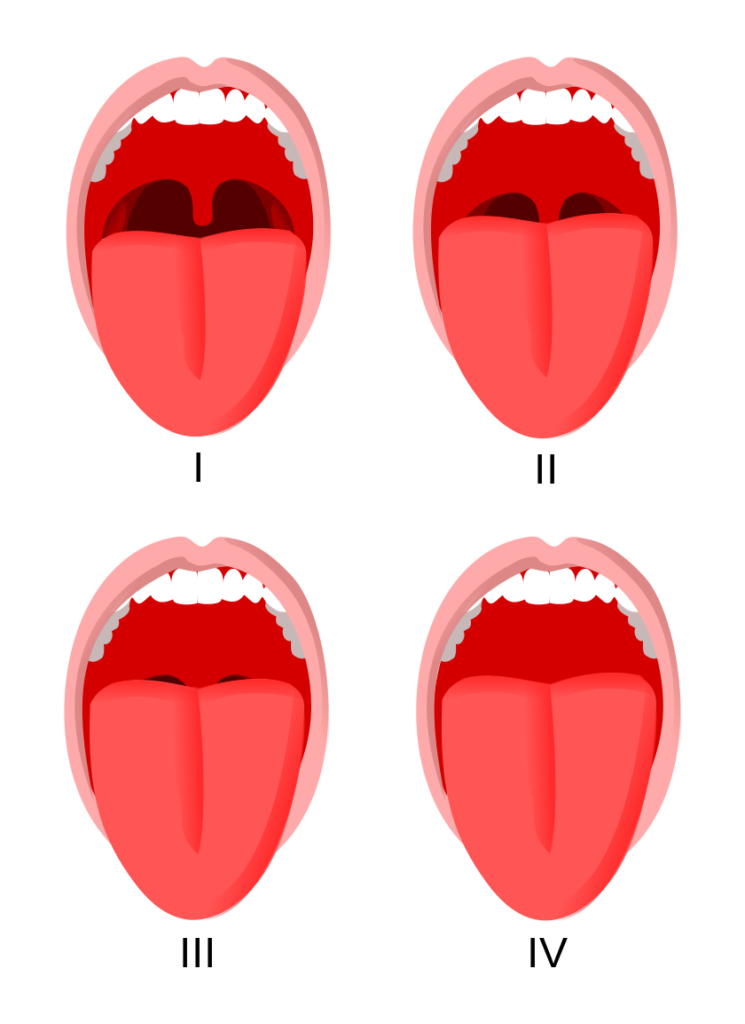

Mallampati

This test measures the soft palate shape with either the tongue sticking out or not.

There are four classes for this score:

- I: Uvula is clearly seen and away from tongue; full visibility of soft palate

- II: Uvula is seen but tip is at the height the tongue

- III: 50% of uvula is visible, the base; can see soft palate and hard

- IV: 0% of uvula is visible; only hard palate

If you by some chance see a uvula deviation, that warrants an automatic referral out, as they are likely dealing with some type of cranial nerve dysfunction.

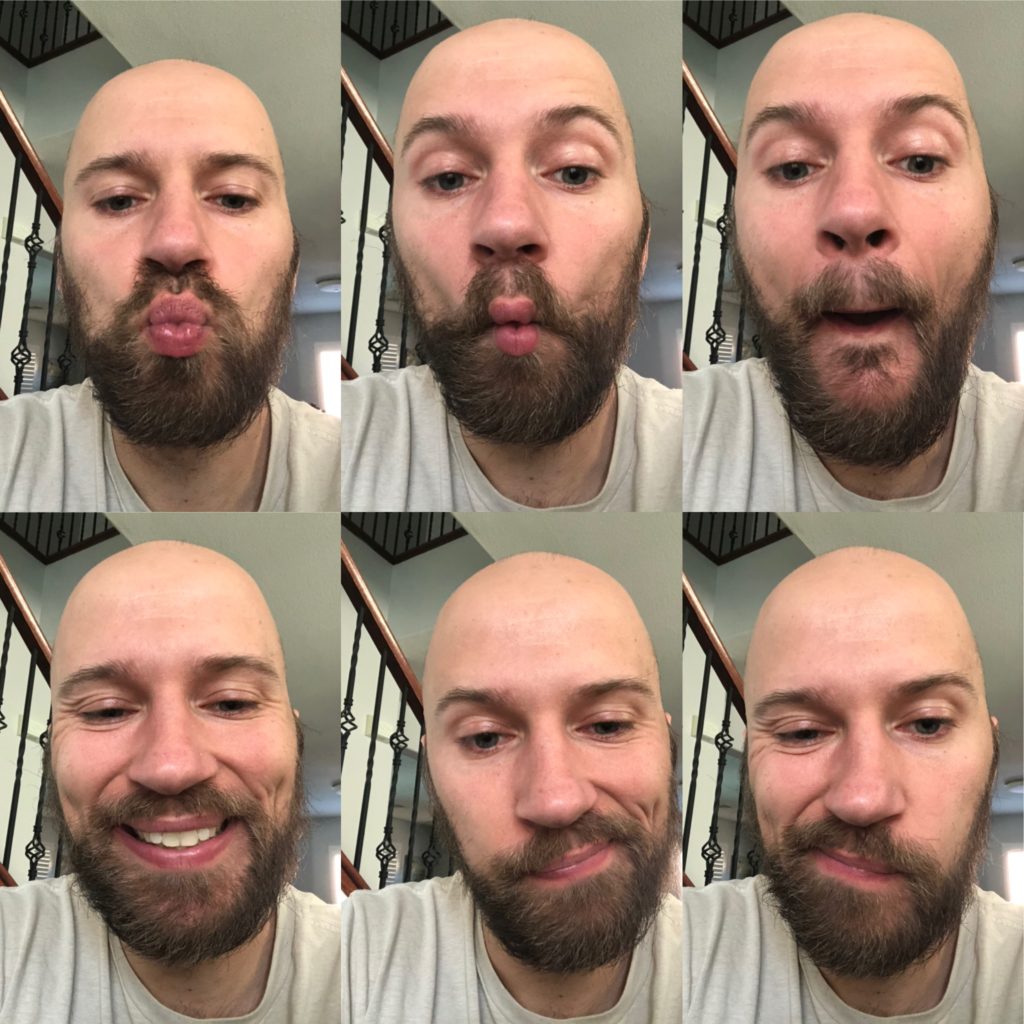

Buccal and Lip Ties

Lip and cheek ties are tissue restrictions that can negatively impact maxilla growth.

Lip ties are where the labial frenulum sits low on the gums, near the teeth. If too low, the individual will have difficulty creating a lip seal.

Buccal ties are where the cheek is adhered to the gums, though there is minimal literature on this presentation. A common finding is an inward inclination of the posterior teeth.

To see how well these fascial systems move, the following actions can be performed as an assessment:

- Lip pucker

- Fish face

- Pop

- Smile

- Side-to-side

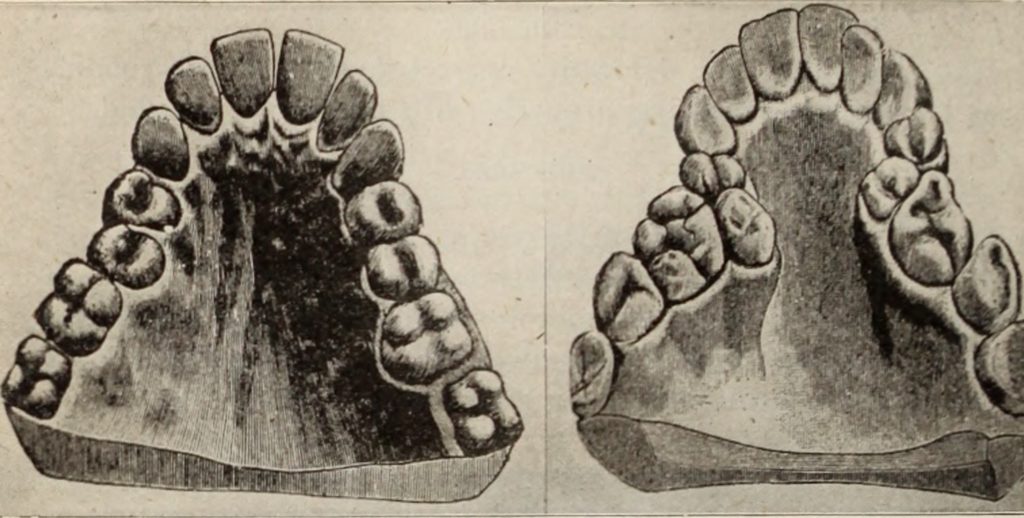

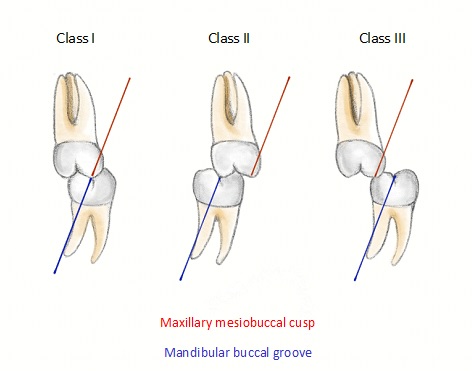

The Dentition

While you can’t necessarily treat or diagnose any dental issues, assessing dental pathology can allow for swifter dental referral.

The “normal” mouth should possess all 32 teeth, have slight overjet (top teeth ahead of the bottom teeth), with light to no contact. There should be the ability to contact one portion of teeth without feeling other portions. This means that if you contact your left molars, you shouldn’t be able to feel anything else.

With this framework in mind, here could be all the things you might see that may warrant a dental referral:

- Excessive overjet or underjet: maxillary teeth are too far forward/backward

- Overbite/underbite – maxillary teeth drop too far down/not down enough

- Anterior open bite – Inability to contact front teeth

- Posterior open bite – Inability to contact lateral teeth

- Crossbite – Teeth tip inward, a valgus angle

- Any mandibular deviation upon opening

- Teeth crowding

You can also look at teeth occlusion, or how teeth contact. Though technically, dentists are the only ones allowed to diagnose a malocclusion:

- Class I: Normal relationship

- Class I malocclusion: Open bite of any kind; overcrowded or rotated teeth

- Class II/division 1 – teeth are tipped anteriorly (often have lip incompetence)

- Class II/division 2 – Teeth are tipped posteriorly

- Class III -underbite

Tongue function

Since the tongue is myofunctional therapy’s major player, we need to find ways to assess this beast.

The most important factor to consider is tongue range of motion. Limited mobility would negatively impact being able to create the palatal tongue position needed for nasal breathing.

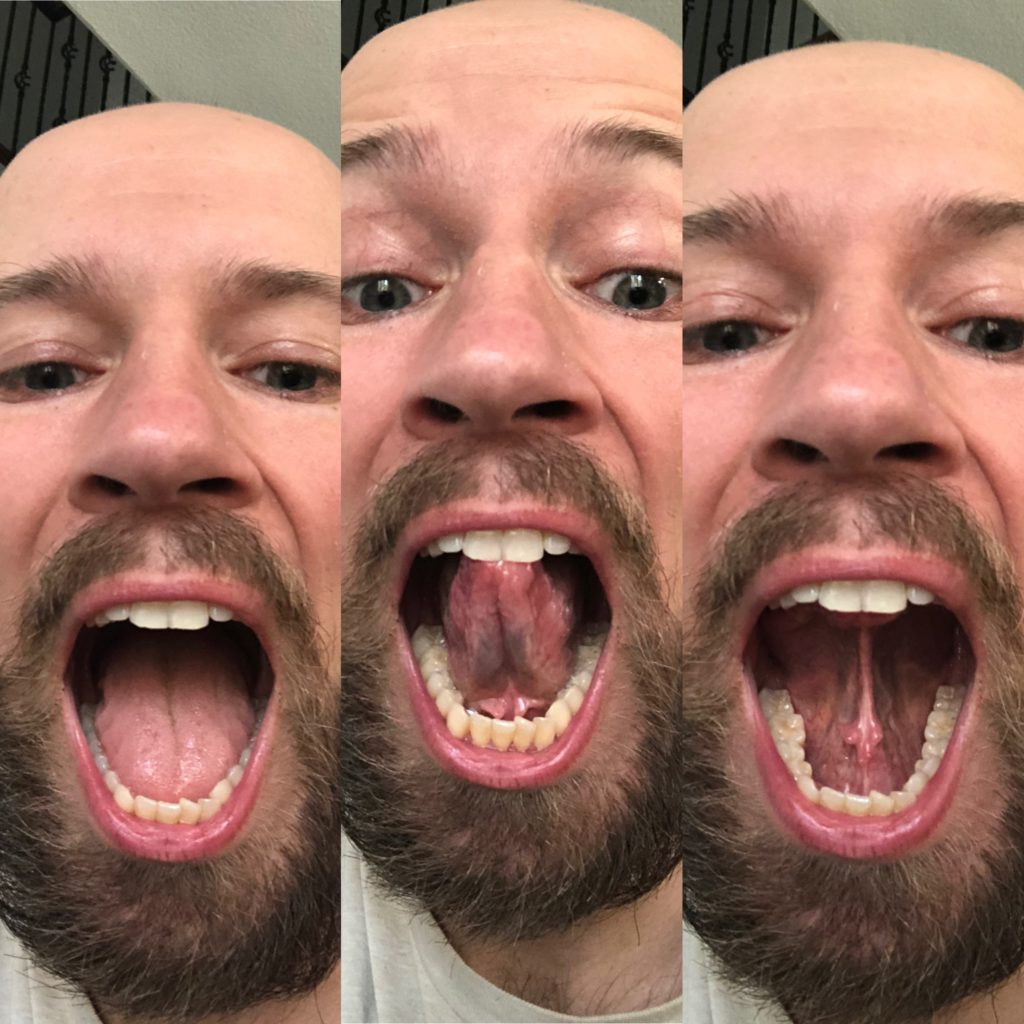

First, one must rule out if there is a tongue tie present. The measure I find most effective is the tongue range of motion ratio (TRMR).

This measure looks at tongue extension as a percentage of maximum mandibular opening.

Here is how you measure it:

- Have the client open their mouth comfortably, but as far as possible

- Next, have the client place the tongue tip on the front of the teeth and open their mouth (anterior tongue mobility)

- Lastly, have the client place the whole tongue on the roof of their mouth and open (posterior tongue mobility). This maneuver is called “the cave”

Though the research really only looks at tongue tip opening for these values, one of the authors of this study (Souresh Zaghi, a badass ENT who did my tongue surgery), looks at the cave as well.

Here’s how the grading looks:

- Grade 1: tongue range of motion ratio is >80%

- Grade 2 50–80%

- Grade 3 < 50%

- Grade 4 < 25%.

While you can get substantial improvements in mobility with myofunctional therapy, Grades 3 and 4 are likely surgical candidates for a tongue-tie release.

Grade 2’s are borderline surgical candidates. For example, some individuals in this category can compensate to this level by lifting the floor of the mouth up during the measure, actually being more restricted than the measure shows. This was me pre-surgery. The best bet with these cases (and all in my opinion) is to start with myofunctional therapy (and regular movement therapy, you can get changes with that as well!).

Range of motion is only one component of a tongue tie. Frenulum location also matters. There are several different types of tongue ties:

- Normal – Underneath the tongue but with normal motion

- Ankyloglossia – attachment is at tongue apex. Upon lifting it looks heart shaped

- Anterior – Attached at any point between tongue midpoint and apex

- Posterior – Underneath the tongue but reduced length. Oftentimes you’ll see a divot int eh tongue

- Combo – anterior and posterior tie; you’ll often see the Eiffel Tower presentation

Treating the Stomatognathic System

Interdisciplinary care is a cornerstone of maximizing stomatognathic health, with several potential interventions. The few that I’d like to highlight are:

- Myofunctional therapy

- Sleep health

- Conventional treatments

Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Myofunctional therapy

Myofunctional therapy involves prescribing focused orofacial exercise to improve upper airway function. The overarching going being attaining a palatal tongue posture and breathing nasally.

Achieving this position occurs by focusing on four stomatognathic functions:

- Oral posture

- Chewing

- Breathing

- Swallowing

This course provided an insane exercise library, which has been quite useful. My only gripe with the class was exercise prescription was protocol-driven. While this plan covers many bases needed for oral functioning, I do not think a one-size-fits-all approach is desirable, as it limits pivotability with non-textbook cases.

With self-trial and error, practicing with patients, and learning from stellar PT Joe Cicinelli, I’ve worked on somewhat of a test-retest method for exercise prescription. This style allows for better individualization in exercise prescription.

My thoughts are there are certain qualities needed to attain a palatal tongue position. I build the posture via the following sequence:

- Lip seal

- Differentiating tongue and jaw movements (including chewing)

- Anterior tongue placement

- Posterolateral tongue placement

- Swallowing

- Habituation

Let’s look at each of these focus areas.

Lip Seal

The lip seal is the first focus area, as creating this seal closes off the oral airway, better promoting nasal breathing.

If the lips cannot contact consistently, the mandible will retrude. This mouth position reduces airway space, negatively affects speech, impacts swallowing, and contributes to drooling.

Establishing a lip seal is not necessarily about lip strength nor tissue extensibility. Facial musculature lacks a crisp stretch reflex.

Instead, lip motor control is the name of the game.

Aside from practicing keeping the lips close together, the three moves I like for this skill are tic tocs, lip curls, and pucker pops.

Here is the tic toc.

and the lip curl

and lastly, the pucker pop.

Differentiating tongue and jaw

Oftentimes, exercises I prescribed to clients would lead to jaw discomfort. The issue turned out to be that excessive jaw movement would occur to compensate for tongue restrictions. Clients would take up all the range that their tongue would allow, then move the jaw to finish the job.

Once I started focusing on both moving the jaw and tongue independent of one another, these complaints began to drop off.

Aside from conventional jaw exercises and the tube chews mentioned previously, my go-to moves are cheek punches and chopstick curls to accomplish this goal.

Here are the chopstick curls.

and the cheek punches.

Anterior Tongue Placement

Anterior tongue placement involves getting the tongue up to the hard palate rugae. This part is the rough ridge on the roof of the mouth, located right before the teeth. When you say the letter “n,” where you tongue tip goes is where you want to be. It’s also called “the spot.”

This position is the first line of defense against mouth breathing, as it requires the tongue to move forward and upward. Limited tongue tip opening may indicate difficulty with anterior tongue placement.

Exercise selection here focuses on increasing forward tongue mobility. For this segment, I like tongue up/down

taco tongue

and lip trace.

Posterolateral Tongue Placement

This is the big dog and by far the toughest part. Here, we need to teach clients to create a maximal palatal tongue posture, reducing encroachment on the airway. If you see a limited cave, you likely need to focus here.

I like to start with generating tension on the lateral tongue. The pointy tongue is a great exercise for that:

Activities that focus on building awareness of posterior tongue rise are also quite useful. Practicing the “gah” or “Kah” sound is quite useful. Then once you get fancy, you can make a fat tongue:

Once you have these components down, then the show begins. Creating and expanding the cave position teaches suctioning on the hard palate and increases posterior tongue mobility:

If you really want to up the difficulty, add resistance by holding water between the tongue and the palate.

Swallowing

Swallowing is the terminal myofunctional exercise.

A good swallow entails keeping the entire tongue up against the palate, and eliciting the swallowing mechanism without compensation (i.e. no neck movements or facial tension). Coaching the smiling swallow is my go-to for teaching this skill.

Habituation

Once these skills are in place, you simply want to cultivate palatal tongue posture awareness. For this, you could set periodic daily reminders to check tongue position.

Sleep interventions

While myofunctional therapy can aid sleep disturbances, many other treatments are often needed in concert.

We will first look at conservative measures, then get progressively aggressive.

Conservative Measures

The first line of defense is to maximize all conservative options.

A few simple focuses can have dramatic influences on sleep quality and quantity:

- Reduce alcohol consumption

- Weight loss

- Positional therapy – sleeping on side can reduce apneic events, as the tongue is prone to retruding when you sleep on your back

- Chin straps or lip taping to promote nasal breathing

Regarding sleep positioning, one must be careful with side sleeping if temperomandibular dysfunction is present. Side sleeping can create a shift in the mandible and place undue stress on the jaw.

Another possible position to consider is sleeping on the back with the head of the bed elevated, as this position has been shown to improve sleep study results.

Lip taping may be useful, though there is not much research touting its efficacy. If you are going to prescribe lip taping, there are a few contraindications:

- Kids younger than 5

- COPD

- Pregnant women

- Suspected alcoholism

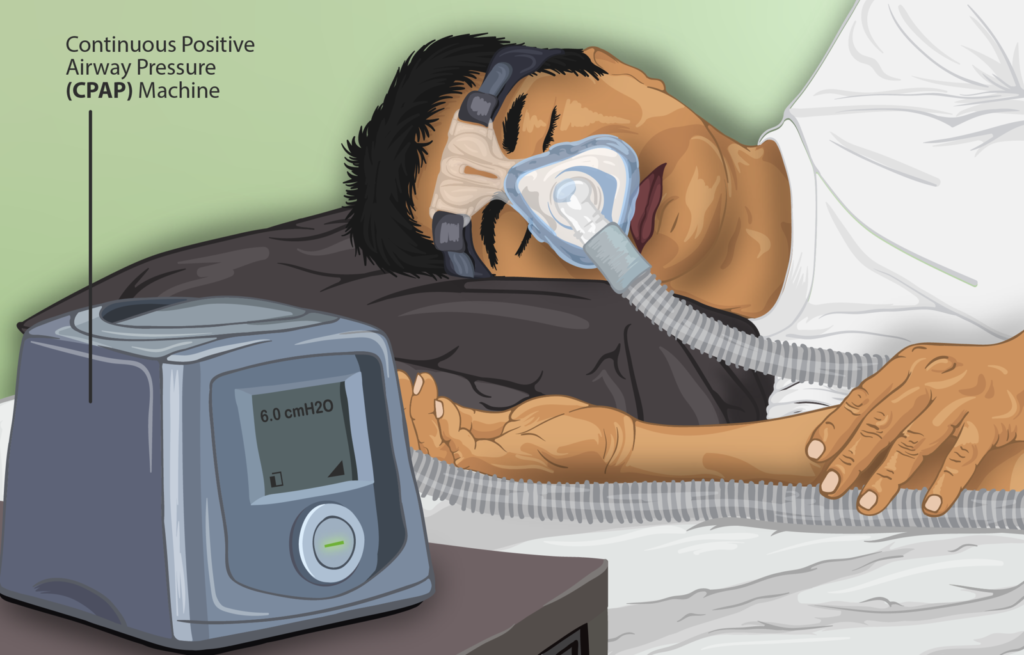

CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a device that blows air down the airway to open up the diameter.

CPAPs can save lives, as it does allow for oxygenation to occur. Unfortunately, it may not prevent cardiovascular events in patients with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea and established cardiovascular disease.

There are also several limitations to CPAP therapy:

- 50% of patients cannot tolerate treatment

- The median compliance rate for those who do average 4.88 +/- 1.9 hours per night, and use it every 2 or 3 nights.

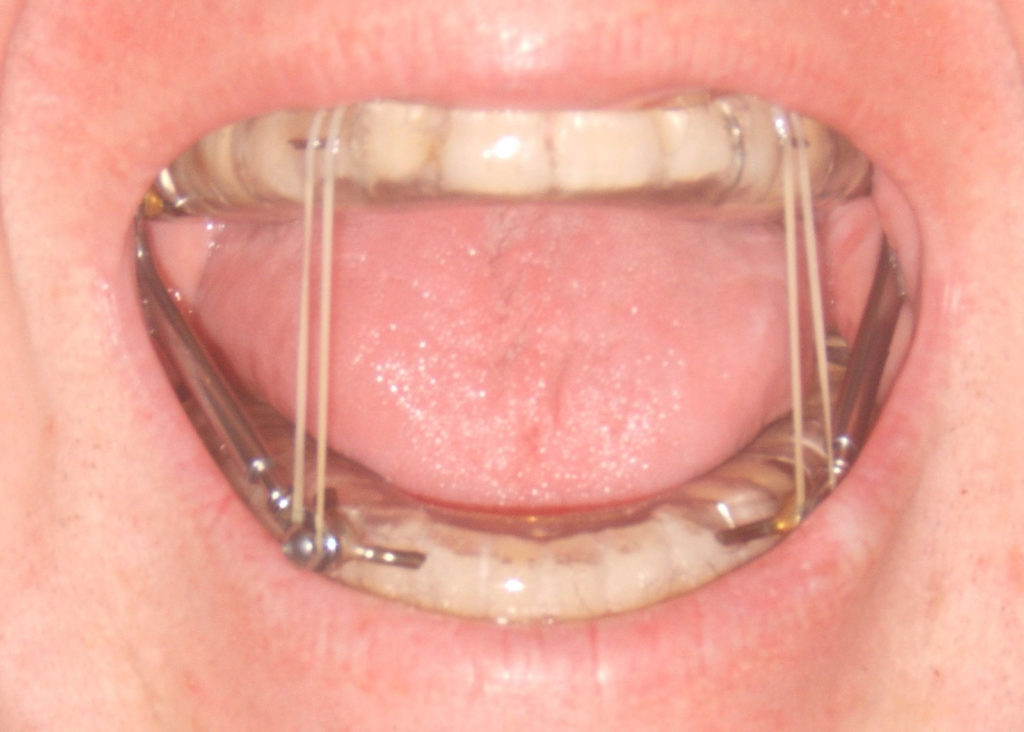

Oral Appliance Therapy

Oral appliances aim to bring the lower jaw forward, opening up the airway. Though to be effective, one must learn how to nasal breathe.

The only downside about oral appliances is that long term use can negatively alter occlusion. Also, if an appliance covers the palate, the palatal tongue posture cannot be achieved. There is no room for the tongue.

Airway Orthodontics

This intervention style combines oral appliance use with orthodontia to increase space for tongue position. This strategy can be useful for those with crowded mouths and narrow palates. It’s what ya boi plans on getting.

With this intervention, appliances are used to move the teeth in a manner that creates more room for the tongue; better allowing a palatal tongue posture. The new position is then sealed with braces.

Surgical Procedures

Several procedures can be performed to increase oral volume and airway space. The big ones we will be talking about are:

- Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy

- Frenuloplasty

- Uvulopaltopharyngoplasty

- Jaw surgery

Let’s look a bit closer into each.

Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy (T&A)

This surgery removes the tonsils and adenoids if they are swollen, which can limit airway dimensions. Generally, insurance will only cover this surgery if one presents with 4 strep infections per year. Advocate for this surgery if you notice high Brodsky scores.

Frenuloplasty – Lingual, Labial, and Buccal

This surgery involves using scalpels or lasers to cut soft tissue restrictions, increasing tissue extensibility. The most common surgery of the three is lingual.

A short lingual fenulum left untreated at birth is associated with OSA at a later age, thus screening should occur with kids.

Obvious restrictions (anterior tongue tie) and borderline cases would likely benefit from the surgery, but all cases should still go with conservative measures first. Performing myofunctional exercises pre-surgery can enhance outcomes, as more tissue may be able to be released.

Uvulopaltopharyngoplasty

A uvulopaltopharyngoplasty is where part of the uvula and soft palate is cut to increase the airway space. In OSA patients, the soft palate can hang down, reducing the airway space.

Though this can lead to positive sleep changes, this surgery is not recommended as it may increase choking risk.

Jaw Surgery

The big surgery is the Maxillary Mandibular Advancement (MMA). This surgery involves cuts on the maxilla and mandible, bringing the entire face forward (and ideally upward, think like a posterior tilt of the face).

Check out this video below, which goes over some of the basics of the procedure:

This surgery helps increase airway space and restores facial features back to their desired development. Though one must be careful with this surgery. If there is a tongue tie present or restrictions, the benefits can top off or even relapse.

Sum up

This course was one of the most comprehensive in a budding field, and it has my strongest recommendation for attendance.

To summarize:

- The palatal tongue posture and nasal breathing promotes optimal functioning of the stomatognathic system

- Orofacial myofunctional disorders have wide-ranging negative effects on the stomatognathic system, including sleep

- Assessing the stomatognathic system involves measuring facial dimensions, skull structure, tongue mobility and function, and oral cavity

- Focusing on improving oral posture, chewing, breathing, and swallowing can favorably impact palatal tongue posture

- Sleep interventions ranging from lip taping, CPAP, and surgical procedures can positively influence sleep quality and quantity

Do you have trouble with mouth breathing? What have you tried to make it better? Comment below and let the fam know!