Do you work with people who are stressed?

Dumb question, right? Who isn’t stressed today? In fact, stress levels are probably at an all time high, and if you’ve read Robert Sapolsky’s work, is likely responsible for most of the conditions and maladies we face today.

The question we must ask though is what role a movement professional has in helping someone mitigate stress?

After attending Seth Oberst’s Stress, Pain, and Movement seminar, I think we now have an answer.

Now I’ve taken a lot of courses in my day, and much of what I learned is the same poop, repackaged as different poop. That’s not to say that new perspectives aren’t useful, but most are looking at the same thing.

Seth’s is the first class that I’ve been to in a hot minute where I had that feeling of “whoa, now this is different.” His approach looks at the struggles our patients and clients deal with through a very unique lens.

To me, this course is the gold standard for learning just how problematic stress is for our patients, and what to do about it. Not only will you get an incredibly in-depth look at stress, autonomics, the nervous system, pain, and so much more, but you’ll learn some excellent methods to aid your clients in mitigating stress. I cannot recommend learning from Seth highly enough. If you want to attend, you can sign up here.

While I won’t go into the great detail that Seth does on the brain, ANS, stress response, and so much more, let’s look at what my big takeaways were.

Table of Contents

Feeling Safe

Many of the problems are patients come in with are secondary to a lack of safety.

There is danger in the tissues (pain), a body tissue is dangerous (autoimmunity), the future is dangerous (anxiety). A lack of safety is the common among all of these conditions.

When the body senses an impending threat, many corresponding outputs occur to protect the body. These actions are used both to mitigate the threat and return the body to its safe point—homeostasis. None of the actions our mind or body make in this instance, or any, are mistakes. All outputs that occur are a necessary response to what a person has experienced.

Pain is among these useful protective outputs, especially when the threat is tissue damage. While pain gets all the love, in reality, pain is only one possible component of a much greater, comprehensive response our bodies undergo: The Stress Response.

Arguably, chronic stress is a much larger source of health problems and healthcare spending than pain. In fact, stress is linked to 75-90% of doctor visits, is the basic cause of 60% of diseases, and costs $1 trillion per year to manage. Stress alters our movement, posture, worldview, and so much more. In a stressful world, invariant behavior is protective, but held too long can create many health consequences.

How in the heck can we as health and fitness professionals help our clients with stress? Well, if the stress response occurs secondary to a lack of safety, then perhaps we can provide some semblance of safety in our client’s lives. This is really where Seth’s approach shines, as many of the skills we possess—touch, movement, healthy behaviors—can facilitate safety within the body.

If we can shift our intervention target away from pain and towards stress, we can help a wider variety of people. Many people lack pain, but most everyone has some type of stress in their lives.

In order to help these people, we must first develop a better understanding of what stress actually is.

Stress 101

Stress is the use of resources to return us to homeostasis. Anything that causes this cascade is considered a “stressor.”

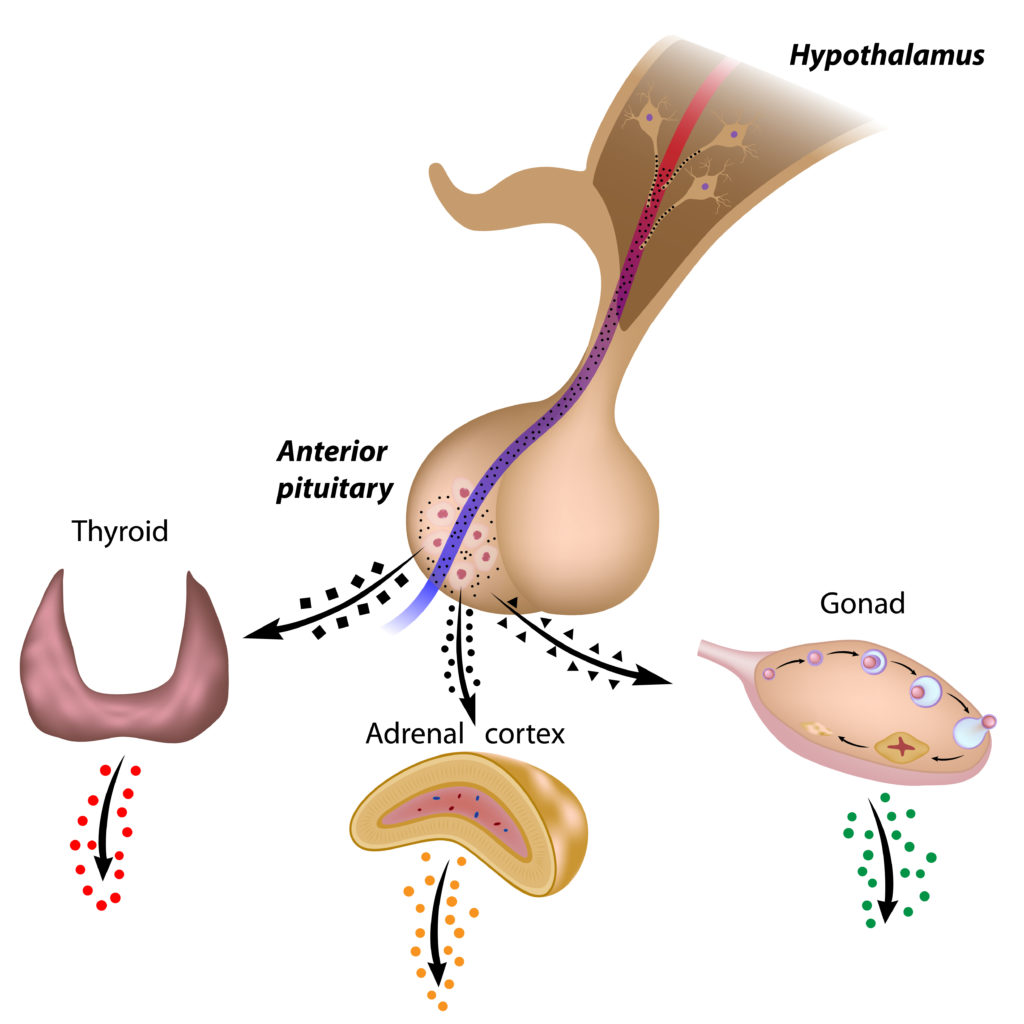

The stress response occurs via the sympathoadrenomedullary axis (SAM axis) and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal axis (HPA axis). These axes release chemicals that prepare our bodies for encountering the impending threat. The SAM axis releases epinephrine and norepinephrine (for the fight or flight response), and the HPA axis releases cortisol (fueling the brain and reducing inflammation). Seth goes into much greater detail on how these mechanisms work in his course, as well as the what and why for various outputs that the body produces.

There are four types of stress that could create this response:

- Positive: That which improves function (e.g. exercise, conversation)

- Tolerable: That which is unenjoyable, yet met with resilience with sufficient recovery.

- Toxic-traumatic: That which endangers the individual due to extreme or unpredictable nature

- Toxic-prolonged: That which accumulates and overwhelms the individual’s ability to respond in a reasonable manner.

The key as to whether the individual can adapt to any of these stressors is duration and intensity. Those stressors which last a long time or are incredibly strong are deleterious to the organism. These changes can alter homeostasis towards a maladaptive setpoint, leading to health issues.

If one has the capability to respond well to stressors, we consider them self-regulated.

Self-Regulation

When one possesses self-regulation, they are able to healthily respond to ongoing internal and external stressors. If the homeostatic set point is disrupted, then the ability to self-regulate reduces.

Chronic stress is a major contributing factor to homeostatic disruption. The increased physiological, psychological, and physical load of chronic stress creates allostatic changes to the homeostatic setpoint, which challenges our ability to adequately respond to stressors. A loss of self-regulation.

The people who cannot self-regulate are likely those clients who make you think that they don’t want to get better. They make you feel uncomfortable, uneasy. They are awkward. Perhaps they are motor morons, or feel like their body is not their own. Maybe they use drugs to artificially self-regulate, or they exercise themselves to oblivion. They feel unsafe within themselves.

These are but a few examples of people who have poor self-regulation. Sounds like most of the people we work with, doesn’t it? The question must be posed: “whatcha gon’ do about it?” The process that Seth utilizes seems to provide some clear steps:

- Recover from tension, stress, pain

- Respond appropriately to future stressors

- Experience the world as new, alive, and worth exploring

Many of these steps come back to feeling safe within our bodies and environment. But what does it take to feel safe?

Safety and Trauma

Safety and threat are evaluated by a sense we have called neuroception. Neuroception is an unconscious process used to determine threat status via sensory information from our viscera, muscles, and other tissues. If we are unsafe, neuroception contributes to starting the stress response within our bodies.

Safety is learned when young. If children have access to these four qualities at least half of the time, a secure neuroceptive map can be developed:

- Reliable access to soothing caregivers

- Rich sensorimotor environment

- Intrinsic sense of safety

- A social group to learn from

Lacking safety as a child substantially increases the likelihood of feeling threatened throughout the lifespan. There is no case greater in which a child’s safety and innocence is lost then if trauma is experienced. Trauma is when a child is exposed to overwhelming stress without caregiver support. Experiencing these types of events as a child has been shown to increase risk of a myriad of conditions, ranging from persistent pain, cancer, heart disease, depression, and so many more. The list you get at Seth’s course will blow your mind.

According to Seth, there are two kinds of trauma:

- Developmental

- Shock

Let’s dive into each:

Developmental Trauma

Developmental trauma is traditionally considered traumatic events occurring from ages 0 to 3, though Seth would argue this age range should increase to age 18. Considering the prefrontal cortex doesn’t fully develop until age 25, could we extend to this age even?

This trauma could also include events that are pre-birth and pre-conception. For example, descendants of holocaust survivors have a higher likelihood of health problems.

Shock Trauma

This type of trauma occurs when the person lacks the ability to appropriately respond to a high intensity or extreme assault. Examples of this could be experiencing violence, rape, accidents, etc.

When trauma is experienced, the body can fall into various protective responses. Looking at the autonomic nervous system can better help us understand which type of response a person is most likely to use.

Autonomics

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) interacts with the central nervous system (CNS), endocrine, and immune systems to form both our stress and relaxation response. It is the ANS that is the primary relay of threat or safety in our internal environment, and is modulated by neuroception.

While I won’t dive as far into the ANS as Seth did, we can look at potential autonomic outputs to consider what protective responses our clients could be utilizing:

- Socialization

- Mobilization with fear (fight or flight response)

- Freeze – Stop and conserve energy

- Mobilization without fear (physical activity)

- Immobilization without fear (intimacy)

Most individuals who have experienced traumatic events without closure either get locked into a fight or flight state, or a freeze state. The former makes us hypervigilant, guarded, and tense. The latter creates disassociation, numbness, stone-walling.

Both cases result in the client being “stuck” in a protective state. To return to self-regulation, the threat response must be completed by signalling somehow that the body is safe.

Providing Safety

Seth uses three methods to facilitate a sense of safety for his clients:

- Safe environment

- Touch

- Movement

Let’s dive into each.

Creating a Safe Environment

Social engagement reduces when a client is experiencing stress. Consider how we isolate ourselves when we are sick or depressed.

We can alter this sense of threat by socially engaging with our clients and providing an environment that encourages the client to feel safe and secure. Achieving a connection with the client can aid him or her in connecting with themselves.

In order to increase a sense of security, the therapeutic interactions should be consistent, standardized, semi-ritualized, non-threatening, and reliable. These components help the patient attune to their environment, and can be fostered by simply being on time and being present. Creating unpredictability within the session can threaten a stressed patient, we want to minimize this within the interaction.

Aside from listening and asking relevant questions, nonverbal communication can also enhance a patient’s sense of safety. Maintaining appropriate eye contact, mirroring the patient’s posture, sitting at the patient’s left or directly next to them can all be useful techniques for building rapport. If the patient still seems uncomfortable, allowing them to change positioning or asking them where they would like to be can prove useful. Also, positioning the patient’s location close to the exit gives an enhanced sense of freedom.

Therapeutic Touch

Safety can be built by reestablishing safe interoceptive sense, which is perceiving how the body feels internally. However, many cannot feel that sense independently, or are excessively interoceptive to where one is hyperaware of all internal senses. Either extreme can be maladaptive.

It is these examples in which therapeutic touch can prove useful. Touch/manual therapy can create a sense of connection and attunement between the patient and practitioner. The patient can begin to trust that the practitioner understands them and their problems; that the practitioner can safely guide the patient towards a safer state of being.

Touch can help assist the patient in regaining appropriate interoception by providing a focus point to come back to. With the type of manual therapy Seth utilizes, the patient is not a passive recipient. Instead, the patient is active and focused in sensing what is going on within the body.

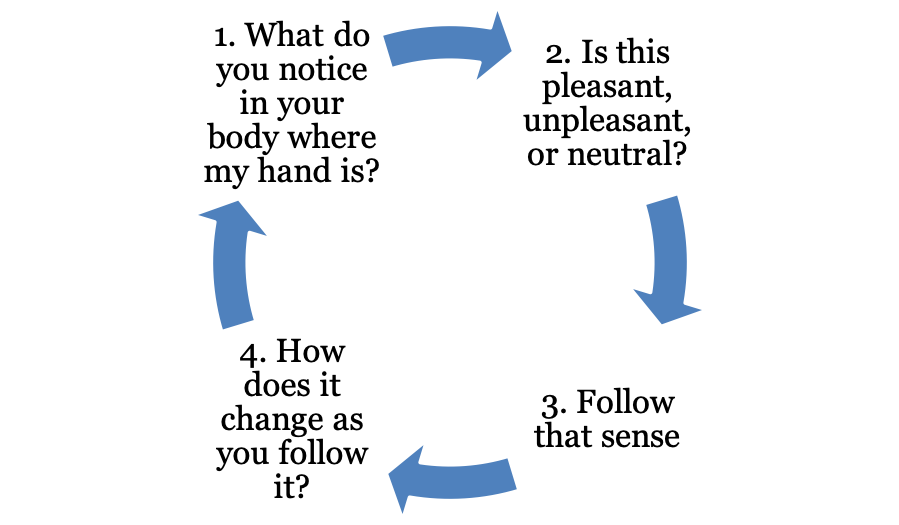

To create this active process, Seth uses a specific line of questioning to help guide the patient through what they are feeling:

If the patient experiences unpleasant sensations during, it can be helpful to associate those sensations with others in the body, enhancing the awareness of what the threatened state feels like.

You’ll generally want to end the manual therapy portion on a high note, i.e. when the patient feels a pleasant or neutral feeling. And if manual contact is uncomfortable for a patient due to previous trauma, the patient can use his or her own hands or objects.

Though Seth uses specific manual techniques which I like, the money is in the process of questioning; of keeping the patient active in re-learning how to perceive his or her body. These questions can be applied to almost any manual technique.

What I really liked were some of the phrases Seth used over the course of treatment. While there were many, a few stood out to me that I am liberally employing with my clients.

- “Can you let yourself feel that?”

- “Let it happen”

- “Can you bring awareness to x?”

- “No, I can’t feel that, but I believe you.”

- “It’s ok to feel that way.”

Movement

The goal of re-patterning movement is to allow the person to move without effort, tension, and fear. The process which Seth prescribes movement is similar to that used with therapeutic touch. The patient is encouraged to direct attention towards an area of the body that feels safe, noticing differences and feelings within their body. One can even go through the same line of questioning and thought process as those asked during manual therapy.

Again, there were specific movement meditations recommended in the class (Seth has a great audio version of these here), but the key is developing awareness. It is the principles mentioned above that help relearn safety.

The techniques that I did find unique to Seth’s class were the vagus nerve stimulation techniques. While they were numerous, my two favorites were gargling water and humming. I was practicing gargling before I would eat, and I did notice a big difference in the amount of bloating I would have after meals, one of the problems I’ve struggled with on and off.

What Progress Looks Like

To gauge progress, we can see changes in these tests, but also in how the client moves and what the client feels. Regarding sensation, they may notice mixed sensations, a space between current sensations (instead of painful and stiff, it’ll be painful or stiff); new experiences, noticing new things, and a reduction of symptoms.

Sum Up

Those were some of the big keys I took away from my first round of Seth’s seminar. I’ve heard him speak a few other times after this course, and as we will find out in later posts, his approach continues to evolve. I cannot recommend you attend his seminar enough.

To summarize:

- Stress is the root cause of many common health issues we see today

- If a person experiences trauma without resolution, that individual will often get stuck in a threat-attenuating state that can have maladaptive consequences

- The key to mitigating this protective response is making the client feel safe

- The key to restoring safety is building interoceptive awareness of what safety feels like in the person’s body.

- The environment, touch, and movement are all useful methods to restore a sense of safety

How have you dealt with stress or trauma in your life? What have you found useful in helping you heal? Comment below and let the fam know!

Photo Credits

All photos are purchased from Adobe Stock