Table of Contents

Learn the key tests to help basketball players move better!

When you work with super tall athletes like basketball players, their movement demands and compensatory strategies are going to appear a bit differently than those of us closer to earth.

But what tests matter the most? What will give us the information needed to make sound training decisions for these athletes?

In order to determine what tests will give us the most information about basketball players, we have to look at what movement challenges they possess, the injuries they are most likely to sustain, and the movement qualities needed to mitigate injury risk.

Be prepared to dive into these areas and take your basketball movement testing to a different level with Movement Debrief Episode 158.

Check it all out below to learn more!

Watch the video below for your viewing pleasure.

Or listen to my sultry voice on the podcast version:

If you want to watch these live, add me on Instagram.

Show notes

Check out Human Matrix promo video below:

Below are some testimonials for the class:

Want to sign up? Click on the following locations below:

September 25th-26th, 2021, Wyckoff, NJ

October 23rd-24th, Philadelphia, PA (Early bird ends September 26th at 11:55pm)

November 6th-7th, 2021, Charlotte, NC (Early bird ends October 3rd at 11:55 pm)

November 20th-21st, 2021 – Colorado Springs, CO (Early bird ends October 22nd at 11:55 pm)

December 4th-5th, 2021 – Las Vegas, NV (Early bird ends November 5th at 11:55 pm)

Or check out this little teaser for Human Matrix home study. Best part is if you attend the live course you’ll get this bad boy for free! (Release date not known yet ?

Here is a signup for my newsletter to get nearly 5 hours and 50 pages of content, access to my free breathing and body mechanics course, a free acute:chronic workload calculator, basketball conditioning program, podcasts, and weekend learning goodies:

Full Name Email AddressGet learning goodies and moreEdit Form | Customize Form

Assessing basketball players

Question: I work with a lot of 6’8 or taller individuals and they present a whole new set of issues than a regular-sized athlete would present. When working with a new taller basketball player, what are 4-5 assessment exercises you would put them through and why?

Answer: Due to the nature of someone that tall, their bodies have to deal with A TON more pressure, meaning there is generally more tension/concentric action just because of structure.

Why do I say that? It’s physics, fam.

Let’s look at the Hagen-Poiseuille equation.

| = | pressure difference between the two ends | |

| = | dynamic viscosity | |

| = | length of pipe | |

| = | volumetric flow rate | |

| = | pi | |

| = | pipe radius |

This looks complicated AF, I get it, but the big takeaway you need to know is this:

Increasing pressure correlates with longer tubes.

Okay cool fam, how can we translate this to humans then?

Uhh…This way:

The taller you are (longer tube), the more concentric muscle tension (pressure) is required to maintain shape.

Having increased tension in stiffness has some utility in the basketball population for sure. It allows them to jump way high, explode off the dribble, and so much more.

But this increased stiffness when loads become too great can be problematic.

Therefore, we need to balance this stiffness out with elasticity. That would entail increasing the following:

- Eccentric capabilities

- Deceleration

Now you could totally argue they need this EVERYWHERE, but we have to look at the most common injuries in basketball, as well as the career enders (at the NBA level). It’s a shortlist, but you’ll see where I’m going:

- Ankle sprains

- Knee pain

- Hamstring strains

- lower back pain

- Other ankle injuries

Ankles and knees composed the overwhelming majority of injuries in the above dataset.

According to the study linked above, 62.4% of injuries were in the lower body.

In terms of what injuries are the career-enders, we have to look at this 2021 study on NBA and WNBA players. The list is short, and definitely not sweet:

- Achilles tendon repairs

- ACL reconstructions

- Meniscal surgeries

- Knee microfracture

If you had to have one of these surgeries, you are playing significantly fewer games one and three years postoperatively. The worst of the worst would be the Achilles tendon repair and the microfracture surgery. Avoid these injuries at all costs!

Given the high incidence of lower extremity injuries, we probably need to do everything possible to make the legs robust AF!

Now, there are a crap ton of different things we could assess to ensure lower extremity function, but let’s assume that you won’t have any access to fancy equipment. These would be the tests I would look at:

- 5-rep max squat

- Hip Flexion

- Ankle Dorsiflexion

- Hop testing

- Bodyfat percentage

Let’s now dive into why I chose each of these tests.

5-rep max squat

The squat movement tells you so darn much for basketball players. First, you’ll get full antigravity eccentric capability at the ankle, knee, and pelvis if you are able to go all the way to the ground (good luck you hoopers).

Qualitatively, watching the squat can also tell you a lot about the compensatory strategy your particular client is using. If you see feet turning out, hips shooting back, etc, you know you are dealing with the pelvis anteriorly orienting.

Interestingly enough, this study demonstrated that a 1-rep max (1-RM) back squat has some modest correlation to sprint times (albeit a small sample size). The downside about this test is that there is an inherent injury risk in assessing a 1-RM, and the movement quality will likely go out the window.

To me, a 5-RM test is likely a better choice. It’s safer, correlates well with 1-RM, and likely gives the player a chance to perform the squat savagely well.

Although the only study I could find looked at back squatting, I would likely prefer a front-loaded variation for testing. The reason being is the front-loaded squats encourage (read: force) players to push the knees forward more, which is going to challenge knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion capabilities. The ability to perform these actions is critical for decelerative capabilities in basketball players.

Hip flexion

Admittedly, looking purely at a squat won’t tell you where the major movement restriction(s) lie, so you need to break it down more than if X-Pac was your quantum mechanics instructor. That’s where these next couple of passive movement tests will be useful.

Hip flexion, the way I do it, kills a lot of proverbial birds. You can determine what rotational action (external or internal) is the limiter, and you can assess knee flexion capabilities simultaneously.

The fact that hip flexion is unilateral can also differentiate any potential rotational compensations occurring within the pelvis.

Ankle dorsiflexion

Testing ankle dorsiflexion can also be quite useful. In fact, this study showed that limited dorsiflexion can increase the risk of developing patellar tendinopathy.

Ankle dorsiflexion in concert with hip flexion can give you an idea of what rotational actions you should target with your movement interventions. If dorsiflexion is limited, you can bet your bottom dollar that calcaneal eversion is non-existent, which can limit both deceleration and force production capabilities. Eversion is needed to appreciate “true” dorsiflexion, and gives the individual a pushing point to move in the desired direction.

I typically test this movement passively on the table. I know the wall ankle drill is common, but there are too many variables that could impact the utility of the test for me. Namely, half-kneeling overbiases internal rotation (most basketball players will have a whack half kneel position), and it’s easy to cheat your way through a good test by pancaking the foot.

Hop testing

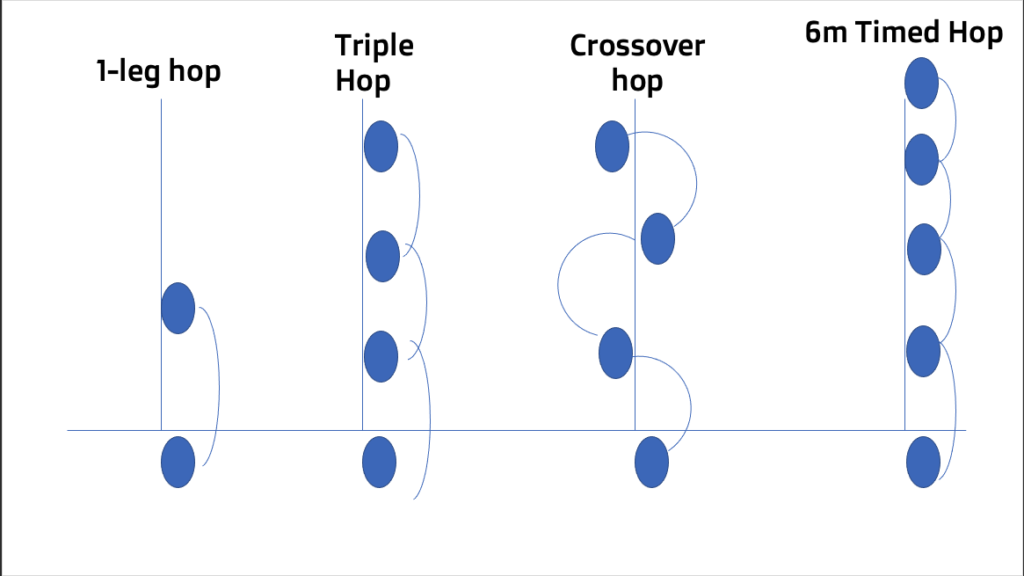

Okay, I cheated. Technically, the hop testing series is composed of four tests, but you look at them as a series for return to play capabilities.

I like these tests because they give you an idea of single-leg lower body power and potential asymmetries. According to this study, they have some predictive capability of injury risk after ACL repair.

The four tests performed within this series include:

- Single leg hop

- Triple hop

- Crossover hop

- 6m timed hop

If you can hit above 80% symmetry, injury risk from a power standpoint is a bit lower.

The one issue with these tests is that symmetry and strategy aren’t fully appreciated. Conceivably, one could produce a fair amount of power while using an undesirable movement strategy during testing. But folks, that’s where looking at the other tests in the cluster can give you a fuller picture.

Bodyfat percentage

This kills me to put this in the cluster, but after peeping this study, I realized bodyfat percentage can be a useful metric to monitor.

Again, the sample size is small, but bodyfat percentage had around an 80% correlation to agility testing, which is pretty dang high. Higher than most anything else I looked at. Moreover, it’s cost-effective to measure, as you can get a cheap set of calipers to do the trick. Also, fam, we are in the fitness business, it’s probably something we should consider important.

The reason why I have to swallow my pride for this test is this was a measure I thought was absolutely stupid and overrated when I was in professional basketball. All of the executives thought this measure was more important than anything, which I thought was silly.

Admittedly, I was wrong. Perhaps the reason why I struggled valuing it is I was not good at getting athletes to adopt healthy behaviors such as eating well and sleeping well to create the body composition changes needed. But perhaps now having access to this data, along with behavior change skills I’ve acquired, could provide useful talking points for my athletes.

Limitations of this test cluster

When you only have five or so tests in your cluster, there are going to be a lot of important things missing.

If we focus solely on the movement side, the broad spectrum testing above can’t adequately isolate variables out as well as I’d like. We can’t make judgments if we need to build eccentric, isometric, or concentric force production, we lack change of direction testing, we are missing other ranges of motion that may be useful to consider.

Moreover, movement testing is only one piece of the puzzle for basketball players. This cluster lacks any sports-specific testing, and we are not looking at load management, nutrition, sleep, and a whole other laundry list of important factors for staying healthy while hooping.

With that said, there are only going to be so many variables within your control. If the game is close, you might not be able to prevent a load spike. You may not have much say in how practice is run. But the aforementioned tests give you a solid sample of variables to consider that can impact a basketball player’s movement capabilties.

Sum up

- Tall people generally have greater stiffness because of their height

- Lower extremity injuries are most common with basketball players

- Testing squatting, hip flexion, ankle dorsiflexion, hopping, and bodyfat percentage pain a broad picture of relevant movement needs for basketball players

- There are limitations to the above test cluster, as many other variables can impact injury risk and performance.

What testing do you like for your basketball players? Comment below and let the fam know!