Table of Contents

If you have a butt wink, collapse your knees and more, you definitely want to read this!

The squat is an excellent exercise for both enhancing lower body range of motion and strength, but it’s not so great if you have a bunch of wild compensations doing it.

What are some of the common compensatory activities that we see in the squat, which ones are “bad,” and most importantly, what shall we do about it?

You’ll get your answer in Movement Debrief Episode 159!

Check it all out below to learn more!

Watch the video below for your viewing pleasure.

Or listen to my sultry voice on the podcast version:

If you want to watch these live, add me on Instagram.

Show notes

Check out Human Matrix promo video below:

Below are some testimonials for the class:

Want to sign up? Click on the following locations below:

October 23rd-24th, Philadelphia, PA (Early bird ends September 26th at 11:55pm)

November 6th-7th, 2021, Charlotte, NC (Early bird ends October 3rd at 11:55 pm)

November 20th-21st, 2021 – Colorado Springs, CO (Early bird ends October 22nd at 11:55 pm)

December 4th-5th, 2021 – Las Vegas, NV (Early bird ends November 5th at 11:55 pm)

Or check out this little teaser for Human Matrix home study. Best part is if you attend the live course you’ll get this bad boy for free! (Release date not known yet ?

Here is a signup for my newsletter to get nearly 5 hours and 50 pages of content, access to my free breathing and body mechanics course, a free acute:chronic workload calculator, basketball conditioning program, podcasts, and weekend learning goodies:

Full Name Email AddressGet learning goodies and moreEdit Form | Customize Form

Knee valgus in a squat

Question: Can you go over knee valgus during a squat ascent in the context of the model? How much is too much?

Answer: It is not uncommon for the knees to cave in as you pop out of the bottom of a squat. But why, fam? Why?

To answer this question, we have to look at what valgus collapse is associated with. And that, my dear fam, is internal rotation.

In order to achieve an internal rotation throughout the lower extremity, the sacrum to some extent must nutate, which helps orient the acetabulum and femurs towards internal rotation. The anterior pelvic floor will also become concentric to assist with force production. This strategy helps distribute the internal rotation action across multiple joints.

But let’s say that’s not enough. Suppose the demands are too great for the above strategy to occur. What’s your next option?

Well, if the pelvis anteriorly tilts, you can change the orientation of the acetabulum so internal rotation can occur without needing relative motion among several joints. Consequently, this may allow the knees to cave in (aka valgus) to assist in the internal rotation behavior.

The above strategy is quite common when ascending out of the bottom of the squat or in max effort Olympic lifts. These positions help favor an internal rotation strategy when your body has to produce a crap-ton of tension to complete a given task.

Now we cannot say whether or not this knee valgus in the context of a squat is a bad thing. This position is definitely not desirable in the literature within a single-leg squat and is also a position often associated with lower extremity injuries. But what seems to be missing in the literature is any research on knee valgus in the context of a bilateral squat.

With that in mind, answering the question of how much is too much depends on a few factors:

- What is the intensity of the lift? – Valgus on your 1 rep max on game day, probably okay, valgus as soon as you descend in a bodyweight squat, probably not.

- Can the person hit desirable depth? – If you can’t hit a desirable depth for the squat at hand,

- Is the body shape desirable? – Are you desiring a more vertical or horizontal pelvic path? The more vertical you require, the less valgus we may want to see

- Is the sensory component desirable? – If your client says “coach/therapist” (do clients call their PT or chiro therapist?), I feel TFL and back on my squat, that’s what you want right? It’s probably not cool. Nor would be pain.

Buttwink in a squat

Question: Make a video on butt wink!

Answer: A butt wink is essentially a posterior orientation of both the pelvis and the lumbar spine.

If you are asking a person to drop their bodies vertically and they can’t through the pelvis, a butt wink is a useful strategy to making this position occur.

Is a butt wink during a squat a bad thing?

It depends.

First off, we don’t have any research either way if it’s potentially injurious. Some evidence exists showing lifting with flexion at low loads is not bad for your back, and also, the lumbar spine becomes kyphotic as soon as a barbell goes onto your back. Therefore, it seems like lumbar flexion is probably going to happen while you squat despite your best effort.

So if we cannot say whether or not this is a bad thing, is it something we’d want to see biomechanics-wise on a squat.

It depends…Again.

What squat variation are we talking about? There will be differences in sacral position pending on where the bar is placed.

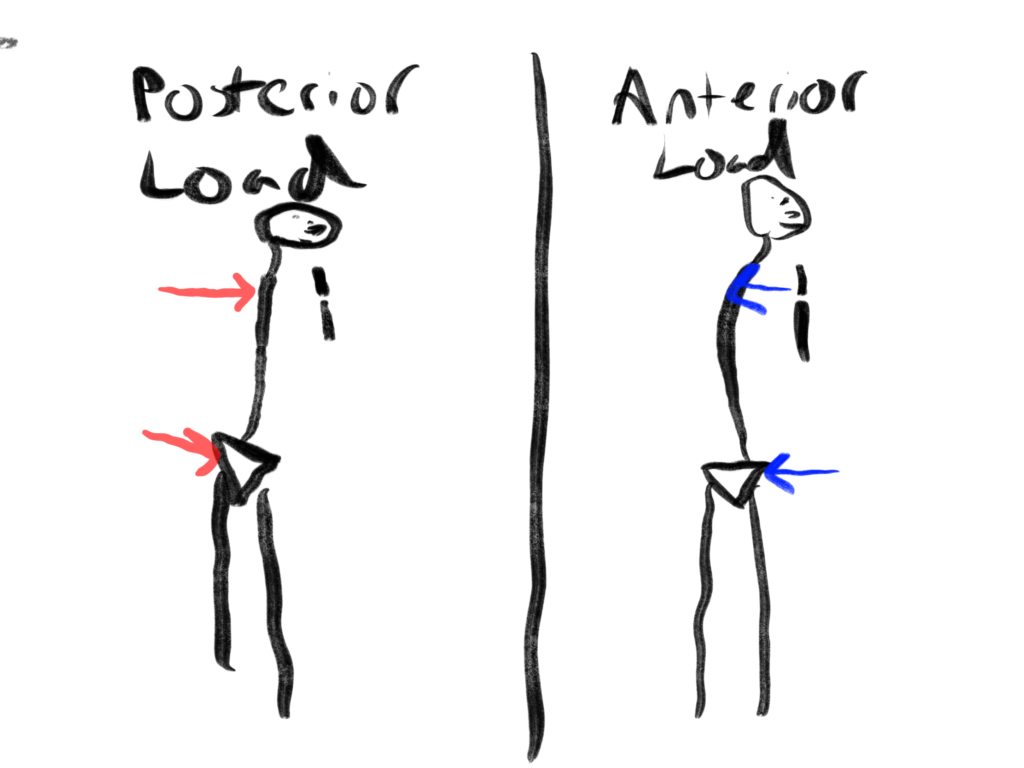

Consider the relationship between the thoracic spine and the sacrum. Both spinal areas exhibit a kyphotic shape. Since you can’t manipulate one area of the spine without likely movement elsewhere, we will often see positions correspondingly change in these areas simultaneously.

If I place a back on the back, the posterior thorax will become more concentric, as the barbell pushes the thorax forward. The corresponding sacral position in this case, the one that mimics the thorax, will be sacral nutation. The nutated sacral position biases the squat towards more posterior displacement.

But fam, in the back squat, I have to get LOW! The way you’ll do that, get to the ground, may be through a slight butt wink.

Therefore, it may be expected to see some degree of butt wink during a back squat.

Contrast the back squat with a front-loaded squat, such as a front squat.

Here, a front squat may allow for some posterior expansion of the thorax, which will correspond with a counternutated sacrum. This sacral position allows for better verticality to occur in a squat. Therefore, I would expect (and hope) that there would be less butt wink in this variation. Why else would you need it, fam? Only if you didn’t have the counternutation skills.

So if you have a posterior load, you’ll likely have more butt wink, and little to no buttwink on an anterior load.

How much is too much? Look at some of the variables we discussed in the previous question, as that will be the guide:

- Can the person hit desirable depth?

- Is the body shape desirable?

- Is the sensory component desirable?

The sticking point in a squat

Question: I often hear about the sticking point in the squat. This usually refers to the ability to come up out of the squat. What about the sticking point going down? Oftentimes going past parallel is difficult.

I see you and others use a heel elevated strategy (inhalation) to help with these compensations. I find that a lightweight held straight out in front does the same thing. An effortless, smooth, fluid perfect full squat with knees pointing forward and not needing to go out. Just doing the squat with an arm in this position doesn’t have the same effect as with a lightweight. Can you talk about the reasons for this?

Answer: With the sticking point, we have a battle between two forces.

And it’s not quite the light and dark side, fam.

Instead, it’s the forces that are pushing you down, and it’s you pushing up against those forces.

When you cannot overcome the difference between these two forces, that is considered the sticking point.

Coming out of the squat sticking point makes sense. You are putting a boatload of force into the ground, and gravity plus the bar are trying to keep you down like THE MAN. When you can overcome these forces by putting A TON of force into the ground, you win. The angels sing, the bird’s chirp, you get a new max.

But what about not being able to break parallel, what’s going on there?

I’M GLAD YOU ASKED!!!!!

It’s the same issue, only in reverse. Here, the forces pushing you past parallel, and your ability to absorb these forces, cannot overcome the force that you are putting into the ground (you are always putting force into the ground to stay upright against gravity. Therefore, you get stuck at parallel #lame.

Being able to break parallel in the squat requires your body to be able to absorb the forces that would push you into the ground effectively. To absorb, you have to be able to create more space and expand the pelvis enough to allow you to descend down.

A heels elevation helps assist with this concept. When you elevate the heels, the legs are oriented in a manner (external rotation) that creates an absorption position in the pelvis (counternutation). This action allows you to hit a lower depth in the squat.

If you can overcome these actions, the force will definitely be strong with you 😉

Midback Hinging During the Front Squat

Question: What can you do to keep better at keeping the upper body back during the front squat when the tendency is to hinge the mid-back during the descent?

Answer: Although a front squat is fairly vertical, the 90-degree arm position does have some bias toward promoting anterior thoracic expansion.

So if you see the upper back hinge forward, your body is merely trying to make up for an inability to put air in the front of the chest.

If you can put air in the front of the chest, the humerus will be able to internally rotate, which happens during 90 degrees of shoulder flexion.

If you can adequately fill the anterior thorax with air, the thorax could anteriorly tilt to make up for an internal rotation deficit. This tilt alters the glenoid position so more internal rotation can be expressed.

The solution, then, is to ensure that one can expand the front of the chest. Utilizing quadruped breathing could be a great choice for a narrow infrasternal angle person.

Whereas our wide infrasternal angle folks might benefit more from something like a pullover.

A squat that helps you move better and build muscle

Question: For a narrow infrasternal angle, what is the best squat variation for both hypertrophy and preserving movement options?

Answer: Maximizing available movement means we need a squat that is relatively vertical, while simultaneously having one that we can do longer sets with higher volume. What squat will allow that?

In my opinion, assuming we aren’t working with a noob who can take advantage of them noobie gains, I’d go with a Hatfield squat.

What’s nice about this squat variation is that the forward reach can assist in the posterior weight shift needed to stay upright on this squat, you can load it pretty heavily, and the support allows you to rep a bunch out. It really is an excellent squatting variation.

Getting more mobility for an overhead squat?

Question: Any go-to mobility drills for overhead squatting?

Answer: Granted it’s not a move I typically go with, but the two big keys that you need to focus on with the overhead squat are:

- Posterior expansion in the pelvis

- Anterior expansion in the thorax.

The former is to get depth, the latter is because the overhead squat position biases internal rotation at the humerus.

Something like a reaching ramp squat can help you acquire the posterior expansion needed to attain depth:

And bar hangs are MONEY for getting air in the front of the chest:

Sum up

- Knee valgus occurs when the pelvis anteriorly orients to help put force into the ground

- Butt wink occurs to help attain depth in a squat

- The sticking point occurs when downward forces and upward forces cannot overcome one another.

- Mid back hinging during the front squat can occur when there is an internal rotation deficit present

- The Hatfield squat can help increase movement capabilities and is a good choice for hypertrophy

- An overhead squat requires posterior expansion in the pelvis and anterior expansion in the thorax.

Photo credit

Photo by Julia Larson from Pexels