Table of Contents

How doing less can actually help you move more

Have you ever tried to rehab someone in pain, but their progress continues to stall because they keep doing activities that cause problems? You know, the person who continues to get in their own way?

Although maintaining a physically active lifestyle is important for one’s health and wellbeing, some activities can be counterproductive during the rehab process. The cure can become the poison.

What are we to do? Stop moving and breathe on the ground FOREVER?

No. God…no.

Instead, we want to couple a stellar rehab program with activity modification, choosing activities that complement or enhance the rehab goal as opposed to getting in the way.

In today’s post, I’m going to show you the following:

- Why activity modification is ESSENTIAL for a successful rehab,

- How NOT modifying activities can create a failure in patient outcomes

- the 3 ways I modify activities to SPEEDILY help some achieve pain-freedom

- How to help patients and clients buy-in to temporarily stopping the tasks they may love, but get in the way.

Sound useful? Check out the video and post below to learn more.

Why activity modification is important

Have you ever seen a high-level powerlifter who is also an elite distance runner? Or vice versa?

Uh, no fam.

The reason why is because achieving excellence in either domain requires mutually exclusive physiological adaptations. Strength training works on neuromuscular force production, and endurance training on oxygen delivery (nerd out here if interested).

Although both qualities can be trained concurrently to a point, adapting your training in one direction will often come at the cost of qualities in the other.

Could the same mutual exclusivity apply in the rehab context? In some individuals, yes.

If your goal is to maximize available movement or be pain-free in a given task, you may have to cease (either temporarily or permanently pending goals) certain activities to pursue the desired adaptation (in this case more movement, less pain, etc).

With this thought process in mind, the goal of activity modification is to minimize interfering activities to pursue a specific rehabilitative adaptation.

There are 3 ways I’ve been modifying activities with great success. As a bonus, you also see how NOT applying these activity modifications caused me great failures.

Here they are!

Eliminating activity

If you are striking your thumb with a hammer, there are many things you could possibly do to improve symptoms:

- Take aspirin (not medical advice)

- Perform thumb manual therapy

- Work on maximizing thumb mobility

- Look at systemic movement influences

But the easiest fix?

STOP HITTING YOUR THUMB WITH THE HAMMER!

This example seems self-evident, but it’s not a strategy I often used unless someone had a serious injury or post-surgical. With most people not being physically active, telling people to stop moving left me torn.

But sometimes, the physical activity in question can be the rate-limiting step, either by reproducing symptoms or by creating an barrier to reaching desired rehab adaptations. If you don’t eliminate these activities (temporarily), your odds of success are slim.

For example, I worked with a woman once who was complaining of asymmetrical feelings within her body, along with general right-sided pain. Major red flags were ruled out.

Finding exercises that didn’t aggravate these symptoms was TOUGH. However, she mentioned to me that she was doing the elliptical for 45 minutes to 2 hours PER DAY! Unsurprisingly, she felt worse after the elliptical. I mean fam, walking was tough to begin with.

I tried to pry a bit about potentially reducing or eliminating this activity, but she was adamant about keeping it, as she wanted to be physically active.

My mistake here was not pushing harder, educating the patient on how the elliptical could hinder progress and her ultimate goal, and informing when we could potentially reinsert this activity. She ended up discontinuing PT.

Now that seems like an easy example of when eliminating the activity could be useful, but what about times when it’s less clear?

Suppose we have a rehab goal to increase range of motion, but someone performs activities that increase muscular tension (e.g. weightlifting), but has no pain while they train?

I worked with a pretty active older gentleman who LOVED the gym and was pretty dang yoked. Unfortunately, his exercise selection was slowly dwindling because of pain and joint replacements. Most hinging and overhead activities were but a dream. However, he was able to get on a training program that he could do pain-free

I evaluated him and he pretty much couldn’t rotate anywhere. Shoulders, hips, NADA. I did some rolling exercises and other low tension activities and was able to pick up a decent amount of motion.

Oftentimes, someone who is overtly muscular can have increased resting tension within their tissues. Think of it as an adaptation from lifting da weights. To lift heavy things, the muscles have to squeeze hard. It makes sense that they’d be “positioned” to squeeze effectively.

However, the less motion that’s available, the less space there is within the joints, which can increase focal pressure along specific areas.

To offset this resting tension, it’s wise to temporarily eliminate high-tension activities like lifting, as it could reduce the efficacy of low-tension activities. Basically, if one thing got you there (aka lifting), we need to try something polar opposite to meet at the middle (aka chillin’).

I had mentioned this to the client, but I didn’t educate or push enough to get buy-in. I didn’t give him a step-by-step plan nor show how we could reintroduce those activities over time. Instead, I sought training workarounds and shored up technique where I could.

It didn’t work.

In both of these cases, making the recommendation to eliminate offending activities would’ve likely enhanced the outcomes.

Eventually, I learned my lesson, and am applying activity limitation with great success.

I have a client I’m seeing right now with thoracic outlet syndrome. He’s an avid rock climber, but unfortunately, climbing was reproducing arm symptoms and numbness. No Bueno.

This individual presented with multidirectional limitations like the gentleman above. A high-tension activity like rock climbing wasn’t going to be our friend.

I had him cease climbing while we worked on reducing overall muscular tension. Instead of rock climbing, I told him things like hiking and biking would be MONEY for his recovery in the short term.

After about 1 month of working on lower tension activities, he was able to hang from a bar for the first time in 9 months WITHOUT SYMPTOMS.

Had we not eliminated the major offending activity (rock climbing), we likely wouldn’t have had the successful outcome as quickly as we did.

I had the same thing with another patient recently who was complaining of shoulder pain. He was another one who was limited in all directions and an avid weightlifter. Instead of finding workaround activities, I had him eliminate lifting for a brief period of time (3 weeks) and again focused on low tension activities. Once I reintroduced a few different safe variations, he texted me the other day saying he was back in the weight room lifting pain-free.

Do not underestimate the power of temporary activity cessation.

But you can’t just stop doing physical activity forever. Eventually, you have to reintroduce higher tension activities. Just like cooking a brisket, you gotta do it slowly.

Slowing the reload

Reloading involves reintroducing higher force/velocity activities to help bridge the gap between low-intensity exercises and the client’s overall goal.

The reload must be carefully thought out and done in a slow and progressive manner, both in intensity and volume.

Commonly, there are two issues that happen during the reload:

- The reload is omitted

- The reload is progressed too quickly

Of course, ya boi has failed at both!

Omitting the reload

I had a couple of folks who were complaining of leg pain while playing sports. In both cases, I neglected to encourage ceasing the offending activity (first mistake), but then I made a different reloading issue with each case.

In the first instance, I did not get to the point of reloading and didn’t adequately educate the client on the progression back to sport. He ended up stopping working with me because of a perceived lack of progress. When really it wasn’t a lack of progress, but a lack of educating him on the plan in my head.

In the other case, the client had mentioned to me that training was bothering his leg as well as his sport, so I took a look at what he was doing in the gym…YIKES.

Let’s just say technique wasn’t where it could’ve been, and many of the plyometrics were far too advanced for where his current skill level.

While I tried to piecemeal together reloading using his current program and coached up his lifts, it was not enough to get a successful outcome.

In retrospect, I should’ve taken over the training program and had him temporarily stop playing his sport until he went through a plyometric progression pain-free. From there, we would’ve slowly reintroduced his sport.

Conversely, I recently had a client who was dealing with calf pain that was aggravated with hiking. Within a couple of sessions he was able to return to hiking pain-free, but the main issue now was feeling weaker in the affected calf. Here, I performed an effective reload by giving him lower extremity strengthening work and a plyometric progression. So far, no issues have crept up.

You have to reload to ensure you have the most success at a pain-free return.

Reload speed

Equally important is the speed of the reload.

If you are taking time off from painful activities, the injured tissues become deconditioned. Therefore, it’s essential to move slowly on the reload. This pace allows the tissues to recondition with minimal flare-ups. Physiology cannot be rushed.

It’s like that one song: “you can’t hurry love.” Imagine me singing it, but about physiology. ITS THAT SERIOUS!

I had a client who was a runner dealing with knee pain. He had a race he wanted to run in 6 weeks, so there was a bit of a time crunch, which I pressured myself to hit.

The first session went really well, we did some activities to increase motion, and he felt pretty solid.

But the pressure was on, and I felt it in the worst way.

Fast forward to the next session. We still needed to recapture some motion, but I thought I might be able to get some changes with some standing isometrics. Nothing crazy, split squats and regular squats. His technique wasn’t the best, but I thought he’d be alright.

Boy was I wrong.

He canceled his next appointment. I reached out and asked what was up. He stated he felt his knee pain was worse after the last session and didn’t want to take the chance of reaggravating it. The race was canceled, the client was lost.

I made the mistake of rushing the client back and forced the reload to happen too quickly.

I vowed to NOT make that mistake again.

Different runner this time who was dealing with hip and leg pain for well over a year. In fact, she had to miss an entire year of cross country and track because of it.

I had her lay off running (step 1) until we were able to safely reload without symptoms.

And fam, you can bet your bottom dollar I took my time.

I started with low intensity activities to restore motion first, keeping the constraints pretty high.

No symptoms.

Then I introduced slow-speed resistance training.

No symptoms.

From there, it was lower level plyometrics, then higher, then strides, then sprints.

All…no…symptoms.

It was at this point that I felt safe returning her to distance running. Plotted with the coach, we used the classic 10% mileage rule, and adjusted along the way; doing combinations of run/walks and longer runs, monitoring symptoms throughout.

She was able to return to track this past year with symptoms only occurring during load spikes, which resolved quickly.

The best part? She hit several PRs in all of her events.

You cannot rush the recovery process, no matter how hard you try. If you progress slowly, you minimize the chances of setbacks and flareups, which will ultimately extend the recovery time back to physical activity.

Activity accommodation

Elimination and reloading are useful for returning to activity, but how can we both maintain conditioning/fitness AND minimize future injury risk?

Here is where I find activity accommodation essential.

Basically, activity accommodation involves choosing supportive activities that will encourage the following:

- Preservation or increase of movement options

- Increase desired physiological adaptations while reducing injury risk

Put simply, activity accommodation involves designing both a training program and lifestyle that pushes the client towards their goals while minimizing risk in the process.

This tactic is especially useful when you cannot eliminate offending activities or don’t have a reloading strategy you can implement.

For example, I have a bodybuilder client who has been dealing with long-standing neck pain. He works 12 hours a day in front of a computer, and cannot budge on this, as it’s his livelihood at stake.

However, he also mentioned that his neck felt worse after training, so I decided to observe a session.

Oh boy.

Although this dude is freaky strong, he was shooting his head forward and crunching, a movement strategy that we established was related to his neck range of motion being limited and painful.

Initially, I coached the snot up out of his current exercise program, gave him four strategies to think about while he trained, and he now actually reports feeling better after lifting weights #winning.

Sort of.

Though I think this is a temporary solution, the bodybuilding style of training is likely not going to help his neck rotation. This is especially true considering his exercise menu has shrunk over the years.

We will be shifting his training focus which require less time under tension and promote more rotation. If we can get a pain-free press (which he currently cannot do), this will be a huge win.

If I wasn’t able to get him to buy into shifting his training, the chances of getting a sustainable outcome would be significantly less. In fact, I’ve seen this with clients I have now who would train a certain way, come to me for damage control, and go back to training with their old tactics.

Band-aids are not the solution, effective training tailored to the individual is.

I’ve seen this time and time again with my training clients, many who are beat-up fit pros. By assessing and desinging an exercise program tailored to them, it’s common to get these outstanding people back to training with few complications.

I would argue it is this piece that is missing from most conventional rehab methods. We do so much to help people get out of pain, but what do we do to encourage them staying pain-free? If we can’t facilitate a long-term program that will help preserve motion and push physiology, the chances of them returning back to us are high.

How to get buy-in?

These strategies are all well and good, but Zac, how do we get clients to buy into these strategies? To slow cooking their return? To (GASP) change the way they train?

What I’ve found to be most effective is plotting the course. Showing them the roadmap to where they want to go.

Telling them their story.

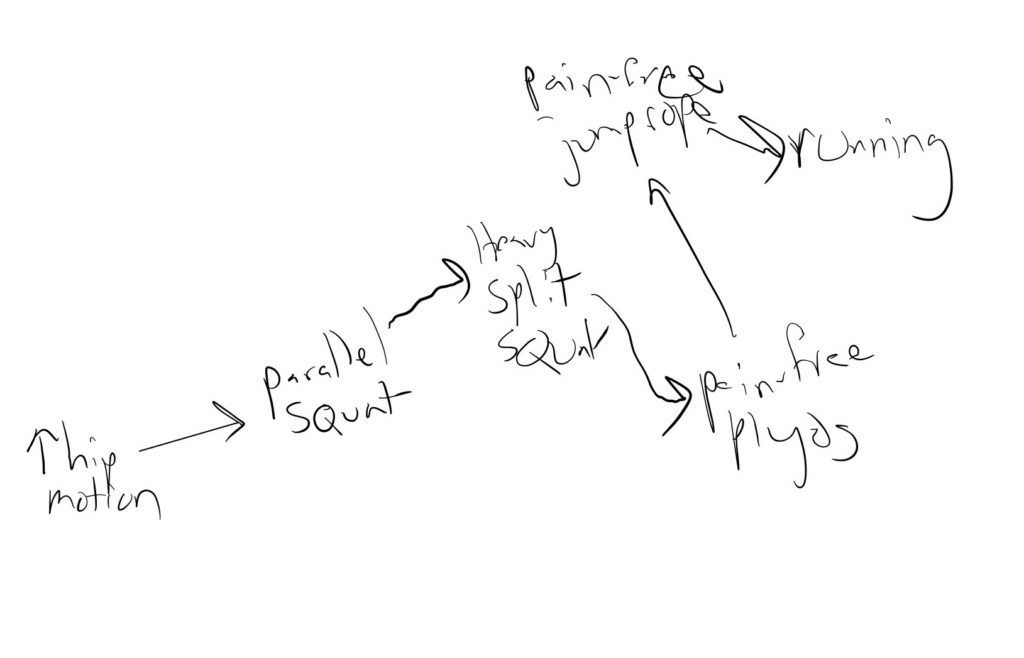

In fact, oftentimes I’ll draw out the steps for my clients so they can gauge where they are at along the program. It might look something like this:

While we can’t necessarily always predict how long each step will take, having this drawing will help the client gauge where they are at along the program. I think had I done this for some of the individuals I failed with, I would’ve had a higher likelihood of long term buy-in.

In fact, I almost had a failure by only verbalizing, not drawing out the story.

Remember that client I talkabout with shoulder pain? The one who LOVES lifting and I told him to stop? That first appointment I gave him low tension activities (rolling) and had him cease lifting for the time being.

He came to me the next appointment and opened with this line:

“I almost fired you because I’m not feeling any better.”

Thank God I got a second go.

After validating his concerns, I plotted out the steps needed to return to lifting and threw in some weights (which I felt based on his testing he was ready for).

He was able to do the lifts pain-free and felt confident in the process.

Had I drawn out the game plan on the first session, saying what we needed before he could get back to lifting, that scare could’ve been avoided. If he could see his next step, it would’ve helped him with buying into the process. Fortunately, I was able to teach him this on the second visit, and he is now lifting pain-free!

Sum up

Modifying activities in a manner that promotes minimizing relapse risk and encourages maximizing movement options is essential for recovery from injuries, and will encourage that you have the most successful return.

To recap:

- Activities that interfere with the rehabilitation goal must be minimized or altered to ensure outcomes are reached.

- Control as many variables as possible.

- Temporarily cease activities counterproductive to the rehabilitation goal.

- Slowly reload back to high-intensity activities, managing both intensity and volume.

- Accommodate training programs and physical activity in a manner that preserves movement options and pushes physiology

- Plot the client’s rehab story to increase buy-in

What struggles have you had with activity modification? Comment below and let the fam know!